There is always someone looking for a house to rent in Chennai.

“Looking for an affordable 2 BHK house in Adyar with a friendly neighbourhood for two working women. We eat meat and invite friends over. Any leads would help”. Posts of this kind flood social media on a daily basis.

Being the fourth most populous metropolitan city in the country, Chennai is home to a large chunk of inter and intra-state floating population, with employment and studies being the major reason for many people from all over the country to move to the city.

Those moving here take help from family and friends, hire brokers, and use social media and several apps and websites to look for rental accommodation. Despite the growing influx of people, one thing remains constant going by what house hunters say: finding a house to rent in Chennai is an uphill task, thanks to the conservative mindset of house owners and restrictions that fail to keep up with changing times.

A tough proposition for single individuals

28-year-old Keerthi* moved to Chennai eight months ago to work as a content writer at an advertising firm. She initially stayed in a hostel located in Nungambakkam for a couple of months, only to realise that the hostel curfews were unviable for her work schedule. That’s when her nightmarish experience of house hunting began in Chennai.

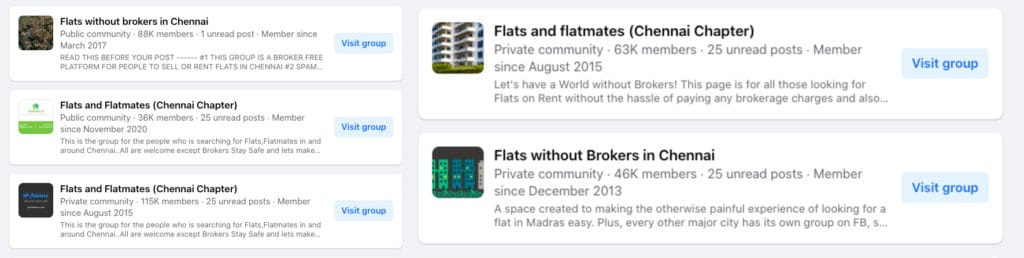

When she contemplated hiring the services of a house broker, the service charges sought by them were as high as a month’s rent. This pushed her to look for a house all by herself. “I first put out a post on my social media feed and also spread the message through my friends. I would note down the contact numbers from the ‘To let’ boards hung outside houses and contact the owners. I would also zero in on the houses in various mobile applications and try contacting the owners directly,” she said.

The first challenge was that there were not many one bedroom houses available at an affordable rent and safety deposit in many areas. Secondly, most of the photos uploaded on the housing mobile applications were misleading. Adding to her house hunting woes were the slew of restrictions listed by the house owners.

“Though I am an adult who is capable of looking after myself, many owners refused point-blank to consider me as a prospective tenant. They said that they do not rent out their homes to unmarried women. Few other owners said that all other houses in the compound were occupied by men, be it a group of bachelors or single men, and therefore it would not be safe for me to be there. One owner asked me to approach them for a house after I get married! Some others who were okay with single women had restrictions about bringing any guests home,” shared Keerthi.

Read more: What you should know before renting a house in Chennai

After two months of tedious searching, Keerthi finally narrowed down her choices to two houses. She preferred the one with a slightly higher rent solely because it would afford greater privacy. “I had to convince the owner that I was completely capable of looking after my safety. The owner said that they had previously only rented out the house to bachelors and never to unmarried women”, she said.

Another factor in her decision was that most neighbours were working professionals who kept to themselves. “I felt like I would not have all eyes and ears on me. Women pay not only for the house but also for safety and privacy,” she noted.

The owners and the neighbours are very watchful of us all the time, said Sharon*, yet another working woman. “Pets are not allowed in our apartment. On one occasion, I received a call from my house owner enquiring if we had pets at our place. It turns out that the neighbours heard sounds of dogs barking from the Instagram reels I was watching and complained to the owner,” she said.

P Gowtham, who works in a private organisation, had recently rented a house in Choolaimedu. “It was a one-bedroom house for a monthly rent of Rs 10,000. I paid a deposit of Rs 50,000. I wanted to live on my own and that was the only reason I rented the house,” he said.

Gowtham explained that before he signed the rental agreement he had clarified with the owner that he would be allowed to have friends over. He also assured the owner that they would not be of any disturbance to the neighbours.

Despite reaching a consensus on this, issues cropped up almost immediately. “On day one, a friend of mine who was a woman came over to help me with moving in. After an hour, I received a call from my owner asking what I was doing with a girl in the house. This irked me but I politely explained to him that he was intruding on my privacy.” The owner then told Gowtham that when he had said he would allow friends over he only meant male friends. “It turned into an ugly argument and I vacated the house on the same day,” said Gowtham, adding that the owner returned the advance only after deducting a month’s rent.

Gowtham added that though Chennai is a large city with many avenues for entertainment, it still is a lonely place for those staying away from family. “Chennai is a place where many individuals learn to live alone for the first time during their adulthood. Unless we have our friends or family over to visit us often, going would get very tough and it could affect our mental health. What we do inside closed doors is not anyone’s business,” he said.

There have also been instances of prospective tenants being profiled on the basis of jobs they hold and denied rental accommodation. Media persons, those from the film industry and lawyers have anecdotally shared that they have had a hard time finding rental homes in Chennai.

Socially marginalised groups experience discrimination

There are added layers to the kind of discrimination faced by those house hunting in Chennai. Many house owners express a preference for vegetarians. Some rent only to those of their own caste location. Others profile prospective tenants based on religion or sexuality.

Aisha*, who works in a Public Relations firm in Mylapore, said that she could not find a house near her workplace, because she was a meat-eater and because she was a Muslim. “While some owners openly told me that they do not rent out houses for Muslims, others were more subtle, saying they only allowed vegetarians,” she noted.

Abinaya* who had a similar experience also said that most of the owners were curious to know her caste. Even when some do not ask their prospective tenants about the same directly, they try and infer it through indirect questions about surnames, names of parents or where family and friends in the city lived.

A 25-year-old software engineer, who sought anonymity, said that though he was a vegetarian he was reluctant to move to homes that were reserved for vegetarians only. “Though I do not eat non-vegetarian food, how can I stop my friends who come over from eating a specific food?” he asked.

While the experiences of unmarried men and women were horrible enough, those of trans persons and same-sex couples are much worse. “We were unable to find a house in the city limits. Firstly because we wouldn’t be accepted in the neighbourhood and secondly because we couldn’t afford the rents. The house owners would not even consider us human and listen or respond to us. Even those who rented the house out ultimately made it a point to add a clause that we should pay the rent by the 1st of every month and if we fail to do so, we should vacate the house the very next day. ,” said Kanmani* a transwoman.

While there is usually some leeway in the date of payment of rent, Kanmani felt that the strict norms were laid down in her case because transpersons have a much harder time finding gainful employment in the city. The house owners were not empathetic to such a situation.

What after moving in?

While it is hard enough to find a house in Chennai, 28-year-old R Rajkiran, who works in an IT firm, said that the battle doesn’t stop at just moving in. He first lived in a single room, which was a repurposed garage, for Rs 7,000 in Thiruvanmiyur. As there was not enough ventilation, he had to move out in three months.

He then rented a one-bedroom apartment for Rs 13,500 in Kasturba Nagar. “Though there were mentions about water shortage in the locality, I did not anticipate it to be as bad as it turned out to be. The water would be available only for an hour in the morning and if I did not wake up at 7 am to ensure storage, there would be no water at all until the next morning,” he said, adding that he moved out in six months and found another house in Adyar.

“The issue with the third house was that the electricity connection was not upgraded to allow for the installation of an air conditioner. Throughout the pandemic, I had to work from home and the house, which did not have enough ventilation, felt more like an oven,” he said.

Rajkiran’s experience mirrors that of many who move in only to find the houses do not look or function as promised. With high security deposits and a notice period, many renters are forced to stay on until they can move to better living conditions.

Similarly, L Shailaja, who had bad experiences in 2015 floods, looked for houses with the main condition that they would not flood during rains. She moved into a house in Trustpuram locality where she was promised that the area would not get flooded and even if it did, the water would drain in a matter of hours.

“It took me only one downpour to know the reality. Soon my house hunt resumed,” she said, adding that the house owners, who police the tenants morally, failed to fix a separate electricity meter for the house. “Despite the government providing electricity free of cost for the first 100 units, they demand Rs 6 to Rs 10 per unit of usage. Also, most owners I’ve come across prefer the rent to be paid in cash over online transactions so as to evade paying tax,” she pointed out.

Read more: Know your rights: Eviction, pressure for rent are illegal during lockdown

What house owners in Chennai say

J Kailash, a house owner from Thiruvanmiyur, argued that many house owners have built their houses with their lifetime earnings. His house was the main source of income for his family. “The problem in renting the house out to a bachelor is that there may be issues with cleanliness and maintenance of the house. If it is a family we do not have to worry about this. Also, we live in a respectable neighbourhood and bachelors having women guests over would raise many eyebrows in the locality. We as owners will be answerable for such issues,” he said.

H Uma, another house owner from KK Nagar, said that there were many safety concerns in renting a house out to unmarried women. “These concerns arise only because we think of their well-being as we would of our own daughter,” she said.

Few other owners Citizen Matters spoke to maintained that their houses were privately owned property and setting curfews or restrictions for tenants was their prerogative.

“There are no laws that help with moral restrictions put forth by the landlords. Even the provisions that exist in the current laws governing tenancy, such as the Tamil Nadu Regulation of Rights and Responsibilities of Landlords and Tenants Act, 2017, are largely in favour of the landlords”, said V Kannadasan, a senior advocate at the Madras High Court, who handles cases of tenancy.

Despite changing times, the experiences of tenants reflect a rigid stance by many house owners in the city. The variety of issues faced by those looking to rent homes shows Chennai has quite a way to go before shedding the tag of being a conservative city.

[* Names changed on request]

Yes. The travails of house hunting for the people described here are indeed daunting and the attitude of the house owners may seem highly unfair and intrusive. However, it should be noted that such caution, suspicions and stipulation of conditions on their part are born out of their own past experiences and real life incidents with tenants, particularly the ‘single’ house hunter, whether ladies or men, and they may not be merely sadistic. They may simply be scared of the “Arab and the camel” story.

I may add that I do NOT live in Chennai and am NOT someone with a house to let anywhere else either.

“Changing times” doesn’t necessarily mean that local people have to change their age old customs, values and traditions. Chennai is one of the bedrocks of Indian culture and heritage. Tenants or visitors regardless of the place they come from must respect and live by local values, traditions and become more acceptable in their new place rather than expect the locals to change as per a tenant’s whimsicals. Conservative mindset is not wrong…it is wrongfully portrayed with a pretext of “changing times”.