The children used to come every evening after school, armed with cricket bats and balls, badminton racquets and footballs. They would descend upon the Chennai Corporation playground at RA Puram in droves, challenging one another to earnest matches.

Anyone driving past on RK Mutt road or Brodies Castle road could see the children at play, occasionally catching thrilling glimpses of solemn contests, joyous victory, or bitter defeat. The kids have all but disappeared today, for CMRL has taken over the playground to undertake work relating to Phase 2 Corridor 3 of the metro expansion plans.

The walking tracks in Panagal Park, T-Nagar share the same fate – according to media reports, the space will be designed to build metro facilities such as entry points for underground stations, ventilation shafts and peripheral walls.

Read more: Why Chennai Metro needs to pay more attention to use of public space

Six parks to become inaccessible due to metro rail

In all, six parks including five corporation parks will be cordoned off to construct stations – Madhavaram Milk Colony, Perambur Market, Perambur Metro, Greenways Road, Adyar Junction and Panagal Park to name a few. The new 118.9km corridor under Metro Phase 2 is expected to be completed by 2026, which means that these parks and playgrounds will remain inaccessible for many years to come.

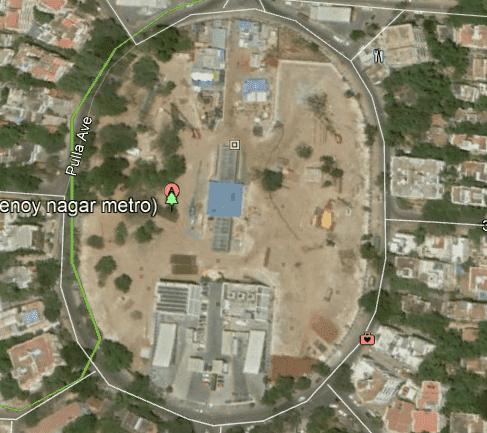

It also means the loss of precious greenery, a resource that Chennai has little of to begin with; the city is said to have the lowest green cover among all metropolitan cities in the country, with only 15 per cent of its land accounting for greenery against the target of 33 per cent as stipulated by the National Forest Policy. According to media reports, Chennai lost more than 220 trees during Phase 1, affecting Thiru Vi Ka Park in Shenoy Nagar, Nehru Park and May Day Park in Chintadripet.

Experts feel that while it is undeniable that the metro expansion is an indispensable civil project, there is scope to minimize the loss of greenery and public spaces. In a quote to the media, Sivasubramaniam Jayaraman from the Institute for Transport and Development Policy pointed out, “Public spaces are activity centres for people. While it may not be possible not to disturb these spaces at all while executing big projects like metro rail, the government should ask consultants to come up with a design without disturbing public spaces.”

Read more: Shenoy Nagar residents fight to save Thiru Vi Ka Park

Public space vs infrastructure projects

Integrating public spaces into large infrastructure projects is not a new idea and Chennai is hardly alone in facing the tricky challenge of balancing development and preservation. Just a few years back, the Delhi Metro Rail Corporation faced similar issues during expansion. While it was inevitable that a certain number of trees were lost to the project, the DMRC is reported to have saved 12,580 trees by re-aligning its blueprint judiciously.

For example, media reports say that a depot at Khyber Pass, Delhi was built at a landfill site to avoid felling trees – the DMRC worked on the landfill to remove all the garbage from the site in order to prepare the ground to lay the tracks. Down south, Bangalore Metro Rail Corporation Limited is being urged to preserve the city’s green resources as well.

Loss of public spaces to metro rail

While it may not be an easy task to balance urban development and preservation, it is hard to imagine that there are no solutions to mitigate the impact. What is concerning is that such an approach does not seem to be a significant concern for Chennai’s civic development body – in the case of Shenoy Nagar for instance, residents were told that Thiru Vi Ka Park would be closed for three years since its takeover in 2010, but today, the site is a sad shadow of its former self and the park is yet to be restored.

The need of the hour is a shift in policy that includes holistic integration as a measure of success in city development projects. The focus should be on preservation, not replacement. For instance, one of the touted success metrics for infrastructure projects tends to be the number of trees planted in lieu of the ones felled – such an approach not only reduces the drive to preserve open greenery, but the new saplings are reported to have a low rate of survival as well.

The authorities would do well to invite the public as well as environmental consultants while planning urban development projects – it may just discover that its balancing act is made a bit easier.

[This story was first published on Madras Musings. It has been republished with permission. The original article can be found here.]