Air-conditioned coaches, swanky stations, easy ticketing options — the infrastructure in Chennai Metro places it at par with similar commute options in developed global cities in most ways. The third largest metro in India, Chennai Metro Rail Limited (CMRL) is also often lauded for connecting the arterial parts of the city and being the fastest mode of transportation.

But when Raghuraman K, a person with visual impairment takes the metro, he does not feel very positive about it. The tactile paving (textured tiles on the ground) doesn’t serve its purpose of assisting visually challenged people with navigation, as a result of which he has to wait for a volunteer or fellow commuter to help him. The wait and every such obstacle he faces reminds him of his disability.

“There is tactile paving in all the metro stations. But it is not of good standard, as my cane is unable to identify it. A lot of people with visual impairment feel the same way,” says Raghuraman, Assistant Professor, Government Arts College, Nandanam. He uses the metro to commute from Guindy to his workplace.

Just as he says, Raghuraman K is not alone. Nor is it an issue faced by those with visual impairment only. Wheelchair users, persons with hearing disability, cane users and other diverse groups who suffer some form of impairment find Chennai metro inaccessible.

Gaps in access

CMRL, on its website talks of metro stations being congenial for the physically-challenged. However, according to an audit conducted in seven metro stations of Chennai by Accessibility India Campaign in 2017, a slew of features needed to make it really disabled-friendly are missing in the Chennai Metro. The report is based on responses from hundreds of persons with disability who have taken the metro.

But CMRL failed to incorporate the features in its stations, even after the issue grabbed headlines in 2017. CMRL had then promised to make its metro stations universally acceptable. But, today none of the 32 metro stations — not even those constructed after 2017 — comply with the Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act, 2016.

In a recent development, a division bench of the Madras High Court ordered notices to CMRL (in August 2020) to make the stations barrier-free. This is based on a Public Interest Litigation (PIL) filed by Vaishnavi Jayakumar, a disability rights activist.

None of the 32 metro stations are in compliance (with the Harmonised Guidelines, Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act 2016 and the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities ratified by India in 2007) despite repeated interventions by domain experts followed by authorities’ promises. CMRL should now retrofit the stations to comply with these basic minimum guidelines, and course correct to ensure that mistakes of this kind are not made in future. A Metro Rail that can be used by all citizens is long overdue.

Vaishnavi Jayakumar, a disability rights activist.

According to the audit report of Accessibility India Campaign and the accounts of many people from the city who spoke to us, following are some of the areas where CMRL really needs to step up its act.

- Slippery flooring in the metro poses a big mobility challenge for clutch users.

- Chennai metro is designed for motorised wheelchair users, not for those who use manual wheelchairs. “It is exerting or often impossible to manoeuvre the ramp with a manual wheelchair,” says Meenakshi Balasubramanian of Equals — Centre for Promotion of Social Justice and a Fellow for Centre for Inclusive Policy. Meenakshi is a wheelchair user.

- Ticketing offices and railways route maps are at the higher level, above the eye contact of wheelchair users.

- Parking facilities are often inaccessible. “You have to park the car at the other side of the station and cross the road, which is a challenge for those with disability,” says Dr Aishwarya Rao, founder of Better World Shelter, a rehabilitation centre for disabled women. Aishwarya is also a wheelchair user.

- The gap between the platform and the train poses serious risks for wheelchair users, as the chair caster could dip into it. “In Switzerland, there is a sliding mechanism that connects the tram station and the trams for the wheelchair to get in. In South Korea, when you press the help button on the platform, volunteers will come with a portable ramp. We should adopt such accessible features,” mentions Meenakshi.

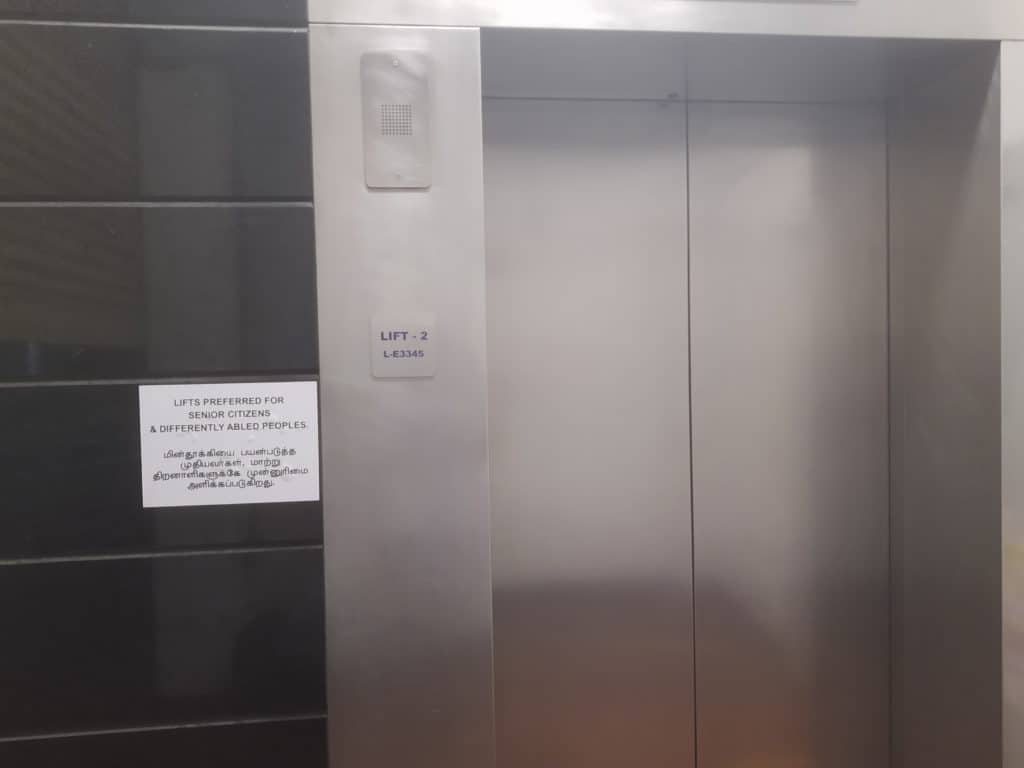

- In fact, the separate entry for wheelchair users in the stations is almost always locked. The authorities open it only when there is a user.

- Problems of last-mile connectivity in Chennai Metro make it inevitably necessary for citizens to use other modes of public transport (which again are not inclusive, but closer). Share-autos run by metros are also not accessible and there seems to be no vision to ensure end to end service for those with disability.

- Sliding doors for accessible toilets (for wheelchair users), anti-reflective flooring which contrasts with walls in colour (to assist people with low vision) and ticket counters with audio induction loop (to help those with hearing disability) are other important features missing in Chennai metro stations.

Despite being aware of the lapses, there seem to be no evident attempts to fill the gaps on the part of the state commissioner for Persons with Disabilities. Multiple calls made to the commissioner to understand their challenges and reasons went unanswered. Other officials in the department are unwilling to comment on the issue.

The way forward

Including persons with disability in mainstream society is not just about deploying volunteers to help them when they need it, but to make them independent by providing all the necessary amenities. Failure to do so has many consequences for a city.

For example, since Chennai Metro has not complied with the standards, people with disabilities are pushed to rely on private transportation. “I wouldn’t have bought a car if public transportation was accessible and inclusive in Chennai. It’s discriminatory against a whole lot of people,” says Meenakshi Balasubramanian.

Before constructing the new metro stations, CMRL should also consult disability rights activists to gather their inputs. A senior Metro Rail official assured us that the department consults the activist groups in every step of the construction. But there are many who do not agree.

Smitha Sadasivan, a disability rights activist, says, “CMRL doesn’t incorporate our suggestions while they are building the new stations. They inform us and ask us to check for accessibility after completion of construction. They do not consider our feedback at this point. as they claim it is too late to change anything.”

Most importantly, the Commissionerate for the Welfare of the Differently-abled (under the Tamil Nadu government) should proactively monitor construction to ensure that the service is inclusive and universally accessible.