How big is your city? Growing up in Chennai, my knowledge and therefore idea of the city extended possibly between school, home, and a few other places I frequented. While this has expanded, I don’t think I realised how big it actually was.

In October 2022, it was reported that the Tamil Nadu government had cleared a 5-fold expansion of the city – from 1189 km2 to 5904 km2.

I was a bit shocked that my city was already 1189 km2 big and now had gotten even larger.

Read more: Holistic plan by CMDA necessary for Chennai’s expansion

What makes Chennai’s boundaries

This got me thinking – how do you define a city?

For most of us, the word conjures up images of grey pavements, tall buildings, concrete and steel, and of course traffic. As a definition, this is inadequate for governance, planning, or research for that matter. Usually, cities are defined by population along with parameters such as what percentage of the residents are engaged in non-agricultural work as per the Census of India.

A word commonly used to denote cities is urban and that leads to the idea of urbanisation that holds that as people congregate in a space and more of them take up non-agricultural livelihoods, it brings in more capital, more people are drawn in, and the cycle continues till the village becomes a town and then a city.

The other defining feature of such urban settlements is that thanks to the nature of the work of its inhabitants, more people can live in a smaller space i.e. higher population density. Definitions are important because only then can we be aware of jurisdictional boundaries.

If I don’t know if I live in the city or in the panchayat, then I wouldn’t know who provides my water, sanitation, street lighting, etc.

So looking at Chennai’s expansion news, I found the media reports were a tad inaccurate in reporting the city’s 5-fold expansion.

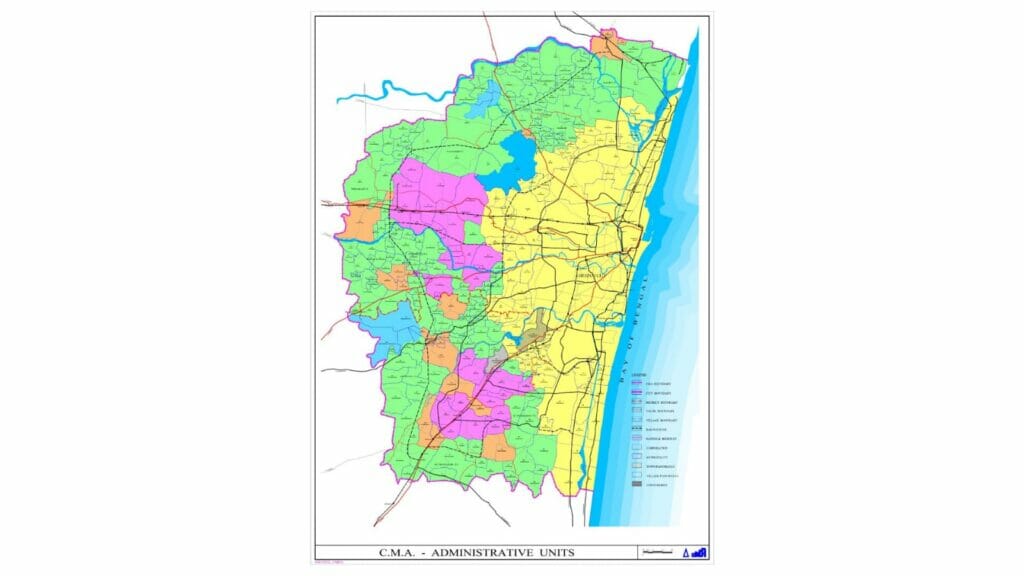

Technically, it was the Chennai Metropolitan Area (CMA) that had been expanded. The city proper continued to be only 429 km2, as it had been since 2011.

So what is the difference between the CMA and the city?

The city (proper, measuring at 429 km2) is the jurisdiction of the municipal corporation – in this case, the Greater Chennai Corporation (GCC) in administrative terms. The GCC is mandated to provide roads, street lights, sanitation, etc.

The CMA refers to a larger area (the city plus peri-urban areas) for which the CMDA (Chennai Metropolitan Development Authority) is responsible in terms of planning i.e deciding the kind and nature of land use, construction, etc. They do this through a master plan as dictated in the Town and Country Planning Act, 1971.

The shaping of Chennai city

While the government is supposed to have regional, city, and local area plans, the focus in India has been purely on city plans (aka master plan). The city master plan is the Holy Bible for urban planning in Indian cities. Chennai’s second master plan covers the years 2008 to 2026. With the second master plan’s end of life coming up soon, the CMDA has begun the process of putting together the third master plan for the next couple of decades.

Of course when planning for the future of a city, the government cannot just consider the formal city limits but has to tap its inner soothsayer. This is because, as discussed earlier, cities tend to grow and even otherwise they impact the surrounding peri-urban areas in terms of accessing water, food, human resources, and of course connectivity (transport).

So cities have to take a big-picture look as well. Hence the need for the CMA.

Read more: How is a Master Plan for Chennai prepared?

What does the expansion of Chennai herald?

The recent expansion of the CMA limits (from 1189 to 5904 km2) raises the question – what purpose does this serve and what is the rationale behind it? The government notification is silent on this.

One argument could be that the city has in reality expanded beyond the 429 km2 and continues to spread. So it makes sense to plan and execute based on actual ground realities. However, experience shows that theory and reality are far apart.

The second masterplan (catering to 1189 km2 of CMA) has not been fully implemented. There has been no review, no course correction, no introspection on the master plan. Part of the reason is the lack of capacity and coordination among the various government bodies involved. While planning is with the CMDA, execution/implementation covers several agencies – municipal corporations, town panchayats, police, highways department, transport department, Metro water, and so on.

So fundamentally, when planning for 1189 km2 has failed, what is the point of expanding the CMA five-fold?

Forget all the bodies involved, let’s look at just GCC which is the biggest municipal corporation in the region, and the oldest one as well with years of experience and a bigger budget than the smaller towns/panchayats in the area.

In 2011, the city (GCC’s jurisdiction) expanded from 174 km2 to 426 km2. A decade later, the newly added areas are still awaiting basic amenities like piped water supply.

Media reports say that though the CMA is now 5904 km2, the 3rd masterplan for Chennai will continue to be for the earlier CMA (1189 km2) and a regional plan will be developed for the extended CMA. Again this raises the question, why expand the CMA then?

The Town and Country Planning Act, 1971 requires regional plans and it is good that the government is finally looking to develop one but does that mean the CMDA will develop both the city masterplan and the regional plan? Do they have the capacity?

What is obvious is the benefit – to the real estate space. Being marked as an urban area or part of a metropolitan area increases the real estate value, and makes it easier to change land use. The CMDA through the masterplan lays out what kind of construction can happen where and also decides the FSI (floor space index) that determines the ratio of built-up area to plot area. Fundamentally this impacts how many floors can be built and thereby the value of the space. The CMDA also is mandated to approve building plans (one of several approvals to be obtained before construction).

Rethinking Chennai’s growth

However, if we are to make our city sustainable, liveable, and circular, this is not the track to take. What Chennai, as do all urban areas in India, needs is cohesive planning at regional and local levels that brings together all stakeholders, including citizens. That plan has to be implemented effectively, with checks and balances, reviews in place so as to factor in hiccups, problems, unexpected deviations and so on.

The city needs to have a vision on where it will be 20 years from now – a sprawling concrete jungle or a compact, liveable, clean, low energy (low carbon) urban space.

For the latter, it will need to preserve its water resources, greenery, promote public transit, look to promote agriculture in urban and peri-urban settings to improve circularity, and decentralise resource management and planning. Key to all of this will be capacity building of all stakeholders involved.

[This story was first published on the blogs of Citizen Consumer and Civic Action Group and has been republished with permission. The original post can be found here.]

Chennai City boundaries should be extended from 426sq.km to 5904sq.km in line with Shangai City (6340sq.km). The megacity will be under the control of Greater Chennai Corporation. This will increase the own revenue of GCC and make it self sustainable instead of relying on grants from Government of Tamil Nadu and India. As we know outer Chennai has many industries, educational institutions, Tech parks and residential areas whoch will generate more property taxes, professional tax, entertainment taxes, etc and this will make the suburbs of Chennai to provide the facilities that current Core City enjoys.