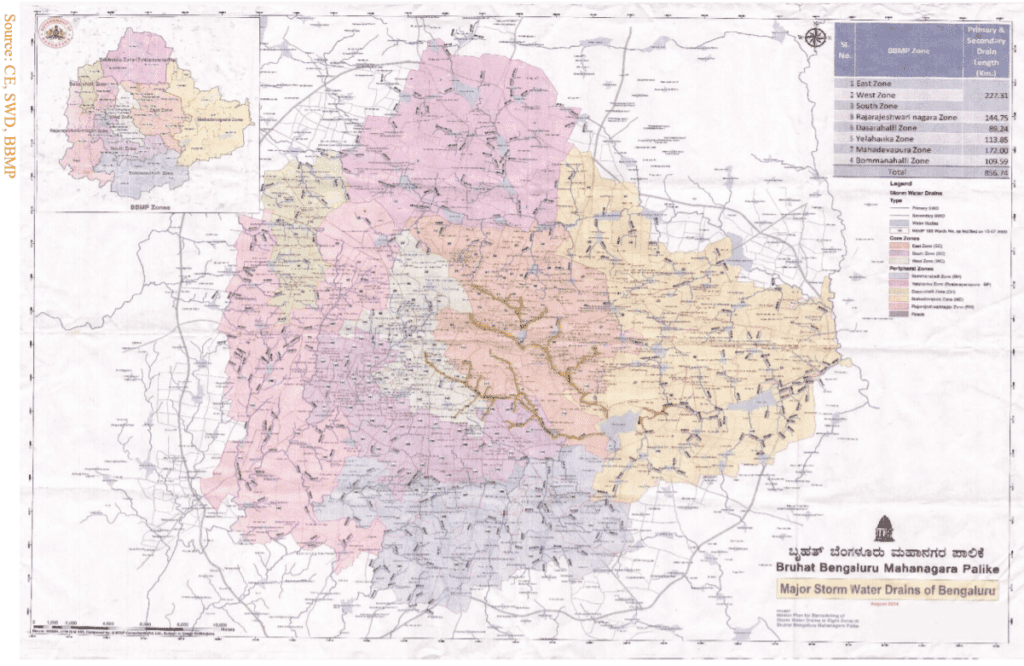

In Part 1 of this series, we saw that a CAG report of 2021 revealed Bengaluru does not have a complete map or database of its stormwater drain network. Drains are mapped in two master plans – the Revised Master Plan (RMP 2015) by the BDA (Bangalore Development Authority), and the BBMP’s master plan of drains. But the former does not indicate the type of drain (primary/secondary/tertiary), and the latter does not include tertiary/roadside drains at all. Neither plan has marked the buffer zones around drains; and many drains are missing in either document or both.

BBMP’s Stormwater Drain (SWD) Department is responsible for maintaining drains and preventing floods. But the lack of data on drains and their capacity means that the city’s drainage network can’t be properly assessed or improved.

SWD Dept has no estimate of water runoff in different areas

As per the National Disaster Management (NDM) guidelines, it’s not just drainage network data that SWD authorities should possess. They should also have a comprehensive database of the different types of roads (including their dimensions, perviousness, gradient, etc) collected at regular intervals, so that water runoff for each road/drain can be quantified. But the audit report says BBMP’s SWD department doesn’t have this data.

Also, despite the city seeing floods for the past several years, no study has been done to assess the capacity of the existing drainage network.

The result: Poorly designed and managed drains

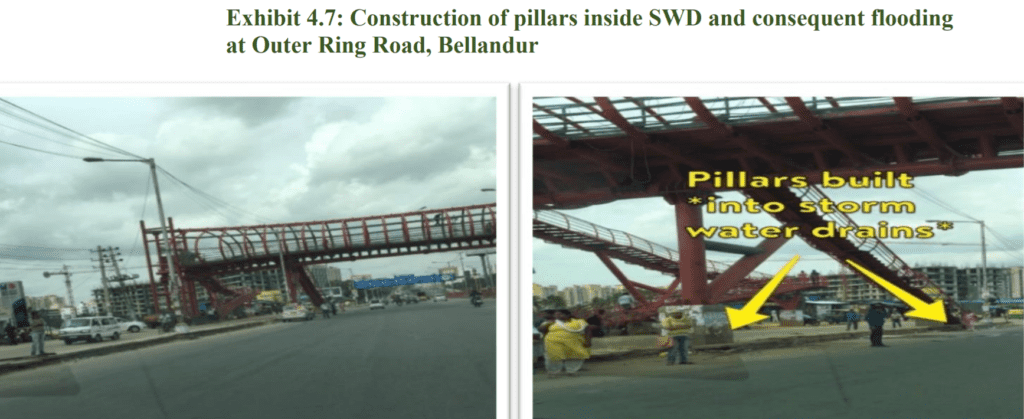

Such lack of data on roads, drains and water runoff affects the design and management of drains, says the CAG report.

The primary parameters for designing a drainage system is the intensity, duration, and frequency of rain in the catchment area. Other parameters include soil permeability, slope, etc. Based on these, the runoff coefficient for each stretch should be calculated, and used to assess and improve the drainage system.

While the drain master plan lacked full data of drains and roads, its calculations on water volume were also off. It did account for rainfall, but not the huge quantities of sewage flowing through drains. The auditors couldn’t figure out how calculations had been made for the drain improvement works, since the SWD Department had not maintained Detailed Project Reports (DPRs) of the works.

Bengaluru-based architect Naresh Narasimhan says, “All SWDs are full of sewage, so when it rains heavily, there is no place in the drain for rainwater. So the rainwater mixes with sewage, flows out, and floods the area.”

Read more: 50% stormwater drains lost: Bengaluru’s flooding is no surprise

Auditors found that flooding was common even in newly-built roads, including TenderSURE roads that cost Rs 10-12 crore per km of construction (as opposed to Rs 2-3 cr for a regular road). This clearly indicates that the stormwater drainage system is deficient in these roads, the report says.

Standards for stormwater drain design, construction and maintenance

The IRC (Indian Road Congress) manuals on urban drainage and road drainage have clear specifications on how stormwater drain systems need to be designed, including surface and subsurface drainage, hydraulic and hydrological design, groundwater recharge, etc. It also mentions special considerations for flyovers and bridges, subways, intersections, etc.

The manuals point out that the design strategy is to let the stormwater falling on a particular catchment area slow, spread and soak within that catchment area itself. IRC guidelines also require regular drain maintenance which includes desilting of drains, clearing obstructions, repairing damaged linings, etc.

BBMP also has general guidelines for the construction and maintenance of city roads, which explain how SWD design is important to prevent waterlogging and ensure roads last well. For example, kerb openings of adequate width at suitable intervals, with grating, are key to preventing road flooding. Maintenance is critical too.

As the guidelines state: “Premonsoon inspection is mandatory to find out the conditions of the drains, kerb openings, etc. The longitudinal and shoulder drains are required to be desilted at regular intervals, especially before and after monsoon periods. Simultaneously, the kerbstone entrance should be cleared to facilitate easy flow of stormwater. Wherever there are longer lengths of covering over the drains and it has been found to be difficult to desilt effectively, hydraulic tests have to be conducted to verify whether the drain is functioning effectively.”

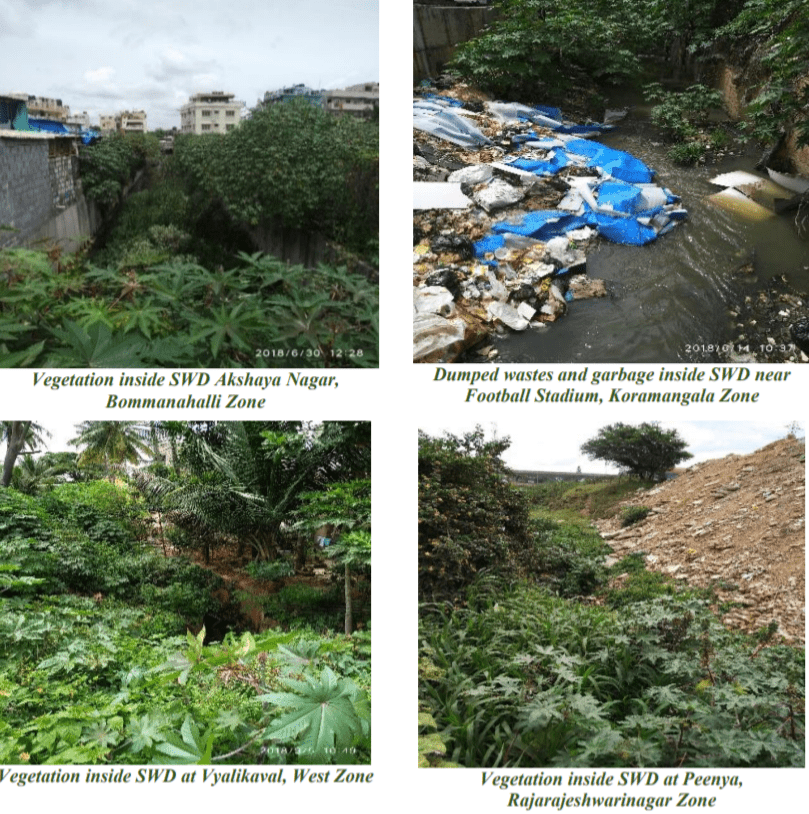

Less than half of stormwater drains maintained

The CAG report finds that these guidelines are ignored. The lack of maintenance had led to drain blockages and damage to drain walls, which result in overflows. Since 2019-20, BBMP has been giving annual maintenance contracts (AMCs) for drain maintenance, but even now, AMC has been given for only 45% of the total drain length (377 km out of 842 km), says the CAG report. The situation was particularly bad in the outer zones, where AMCs were given for less than 50% of the drain length. BBMP also neither maintains records of drain inspections nor prepares action plans for drain maintenance, says the CAG report.

Naresh says, “About 2 m of silt is caked at the bottom of drains, which reduces their capacity. Silting is a continuous problem, and the drain has to be maintained every year. BBMP keeps giving contracts for desilting, but the contractors don’t do a proper job at all – they don’t take the silt out and expose the drain bed. They remove the silt and put it next to drain; and in the next rain, the silt flows back into the drain.”

Besides, IRC and NDM guidelines require desilting of drains before monsoon. But records from the audit period (2013-14 to 2017-18) showed that many of these works were done during the monsoon itself. Desilting works were given to contractors between July and November, and they were allowed time ranging from one month to 24 months to complete the works. Also, desilting was done only in select stretches of drains, which meant that silt from upstream could still flow downstream and defeat the whole purpose of desilting.

Use stormwater drains to recharge groundwater

Given the groundwater depletion in cities, the IRC guidelines stipulate that all urban drains should be used to raise the groundwater table. This can be done by building recharge wells within drains, having drains with porous layers, building detention and retention ponds (to temporarily hold water and later use it for groundwater recharge, etc). All these recharge methods should be used before rainwater is ultimately disposed, which would also reduce the chance of floods.

NDM guidelines too mention the need for recharge structures within drains.

Read more: Two years, one lakh wells: Can ‘million wells’ movement help solve Bengaluru’s water crisis?

But Bengaluru has made no such efforts. While the drains completely lack recharge structures, they are also fully concretised so water cannot seep into the ground. Responding to the audit report, the state government said the reason for this was the high levels of sewage and industrial waste in the drains; if recharge structures are built inside drains, sewage would seep down and groundwater would get polluted. The audit report says that the government’s reply is unacceptable since sewerage lines shouldn’t have been laid inside drains at all, as per the law.

No policy on stormwater management

Clearly, stormwater drains in Bengaluru are not designed as per national guidelines. Also, the state still does not have a policy that addresses stormwater management or looks at stormwater as a resource.

[But what about works worth crores of rupees that BBMP had got done on SWDs over the years? Why have those works not improved the situation? We explore this in Part 3 of this series.]

The need of the hour is to introduce Recharge Pit below Drain Layout/Footpath ( at spacing of 500m) of 1m diameter- 3m deep; Provide(from bottom): 40mm aggregate-1m deep; 20mm aggregate-0.5m deep; Sieved Coarse Sand-0.25m deep; Activated Charcoal- 0.25m deep; Sieved Coarse Sand- 0.25m deep: Place manhole cover.

Looking forward to the part 3.

Please find Part 3 here: https://bengaluru.citizenmatters.in/cag-report-stormwater-drain-works-no-accountability-70663