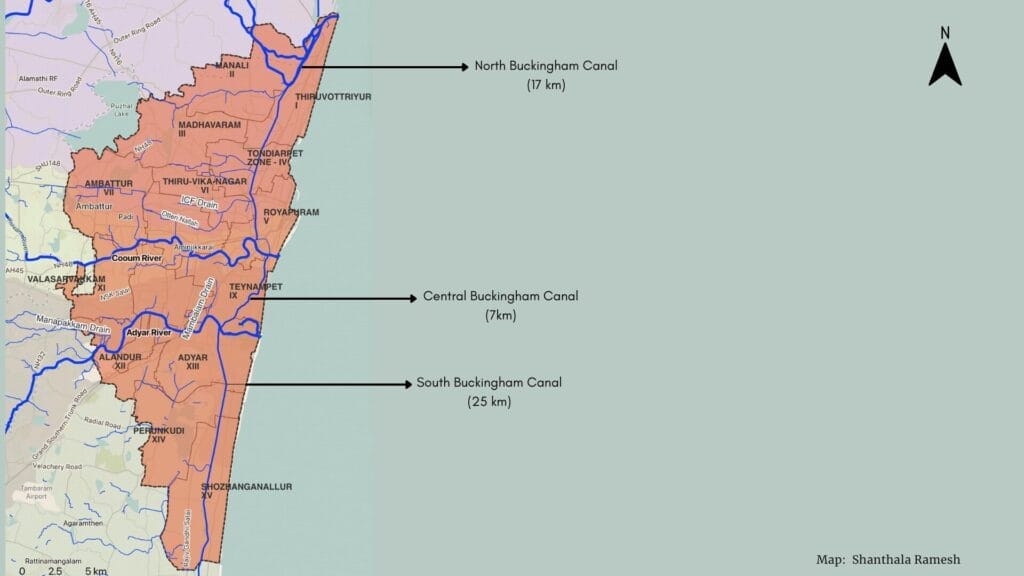

It has been over two centuries since the construction of the Buckingham Canal, a once vital navigational route stretching from Pedda Ganjam in Andhra Pradesh to Marakkanam in Tamil Nadu. At its peak, the canal could carry 5,600 cubic feet per second (cusecs) of water. However, decades of unplanned urbanisation have drastically reduced its capacity to just 2,850 cusecs with the Mass Rapid Transit System (MRTS) being the major encroacher.

Regular desilting is crucial for maintaining the Buckingham Canal, yet its upkeep has been a significant challenge since the early 20th century. Over the years, numerous proposals to restore and beautify the canal have been put forward, but most have either stalled or failed to bring about any substantial change.

Every monsoon, discussions on the Buckingham Canal’s vital role in Chennai’s flood mitigation resurface, drawing attention to its deteriorating state. In September 2022, the Madras High Court issued a stern rebuke to the government, ordering it to demarcate the canal’s boundaries within six months and clear encroachments within a year. The court specifically instructed that all structures obstructing the canal — except for the pillars of the Mass Rapid Transit System (MRTS), flyovers, and bridges — should be removed to restore its navigability.

A restoration project that wasn’t

In response, the Water Resources Department (WRD), the canal’s custodian, submitted a detailed project report to the State government in October 2023 outlining a large-scale restoration plan. The project was expected to cost ₹1696.5 crore. Of this, Chennai Rivers Restoration Trust was to invest ₹716.5 crore and WRD was expected to invest ₹980 crore.

By 2023, it was reported that 40% of the work to demarcate the canal’s boundaries, primarily in the northern and southern stretches up to Marakkanam, had been completed. However, progress in the central portions of the canal has been hindered by strong resistance from local residents.

The Tamil Nadu government recently announced it will abandon the proposed restoration projects for the Buckingham Canal in the Chepauk-Triplicane and Mylapore constituencies, due to a severe shortage of funds. This major setback raises uncertainty about the future of the canal’s restoration.

Read more: Winning ideas to revive Buckingham Canal and make Chennai climate-proof

Diverging visions: Central vs State government

The Central and State governments have contrasting views on the Buckingham Canal’s restoration. The Centre views the canal primarily as a navigational route. In 2010, it allocated ₹1,515 crore for its development between Kakinada and Puducherry. The Inland Waterways Authority of India (IWAI) conducted a feasibility study, which deemed the stretch between Andhra Pradesh and Ennore Creek viable for navigation, leading to funding for the project in Andhra Pradesh.

However, once the canal enters Tamil Nadu, its width narrows significantly due to extensive encroachments, particularly from the MRTS.

“This prompted the IWAI’s 2010 Detailed Project Report (DPR) to conclude that the canal’s stretch within Chennai was no longer viable for navigation. As a result, the Central government ceased further funding in this region,” notes N Udhayarajan, Director of the Uvakai Research Foundation, who has extensively studied the canal.

Meanwhile, the State government views the Buckingham Canal as a drainage channel. In addition to runoff from rivers like the Adyar and Cooum, untreated sewage is routinely dumped into the canal at multiple points throughout the city.

Despite several attempts to improve drainage and flood mitigation, the canal’s ecological and functional potential remains underutilised. As Udhayarajan notes, “The State sees the canal’s relevance solely as a flood mitigator, but even in that role, it has failed to perform effectively.”

Neglecting ecological value

Moreover, the government overlooks a crucial aspect of the Buckingham Canal: its role in the coastal ecosystem. Although it is a man-made channel, it has become vital to the region’s biodiversity over time, connecting key ecological zones like the Pallikaranai Marshland, Ennore Creek, and major rivers.

Madhan Karthik, a researcher, highlights the canal’s environmental decline, noting that bee-eaters and dragonflies, once vital to controlling insects and mosquitoes, whose numbers have declined due to pollution. Untreated sewage and waste in the canal foster mosquito breeding and are a public health risk.

Read more: Cement dumping at Buckingham Canal threatens South Chennai’s flood drainage system

Lack of clear vision for restoration

The plan to restore the Buckingham Canal lacks a clear, unified vision. “A restoration plan cannot succeed unless we first define the purpose for restoring the canal,” Udhayarajan explains. Without a clear goal, it is impossible to allocate funds or resources effectively.

WRD Minister Duraimurugan recently proposed handing over non-irrigation water bodies to local civic bodies for better upkeep, with the Virugambakkam and Otteri Nullah canals already transferred to the GCC. There is speculation that the Buckingham Canal may follow suit.

Regulatory and waste management challenges

Beyond funding, the restoration efforts face numerous regulatory challenges. One of the most pressing issues is the pollution caused by untreated sewage. Raw sewage is frequently discharged into Chennai’s water bodies, including the Buckingham Canal, further deteriorating its water quality.

A 2021 audit by the Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG) revealed that 242.73 million litres of untreated sewage are illegally dumped daily into the canal and other water bodies.

Another major issue is the dumping of construction debris. “Large quantities of construction waste, cement debris and other solid waste including thermocol and milk packets, are regularly dumped into the canal, especially near Sholinganallur and Pallikaranai Marsh. Some of this waste, including debris from Metro Rail construction, is linked to government projects,” says Madhan.

This debris blocks the canal’s flow, flooding neighbourhoods across South Chennai. With similar issues in North Chennai, the Buckingham Canal is just 30 metres wide and requires immediate widening. “A multi-disciplinary committee is necessary to monitor and address this issue,” he adds.

We reached out to WRD officials for comment but were informed they would not be available until January due to ongoing flood mitigation work. We also contacted the CMDA to inquire whether the Buckingham Canal restoration would be included in the Third Master Plan but did not receive a response.

A call for purpose-driven restoration

The future of Chennai’s flood resilience hinges on restoring the Buckingham Canal to its full potential.

The canal’s design also presents challenges. Unlike most rivers, which run perpendicular to the sea, the Buckingham Canal runs parallel to the coastline, cutting through the city longitudinally. This lack of slope means that deepening the canal is not feasible, as it could lead to seawater intrusion. The only viable solution is to widen the canal to restore its flow capacity. “This is why we cannot apply the same restoration template to the Buckingham Canal as we would for other natural canals or waterbodies,” says Raju, an environment researcher.

A focused restoration effort must first understand the canal’s current-day relevance and plan accordingly. This means integrating flood mitigation, biodiversity protection, and effective sewage management into the restoration plan. Only with a clear, purpose-driven vision can the canal be restored to its former significance, benefiting both the environment and the people of Chennai.