A few not at all fun snippets from the discussion.

- “99% of the earth’s resources are consumed by 1% of the world’s population, with the remaining 1% resources being fought over by 99% of the population”.

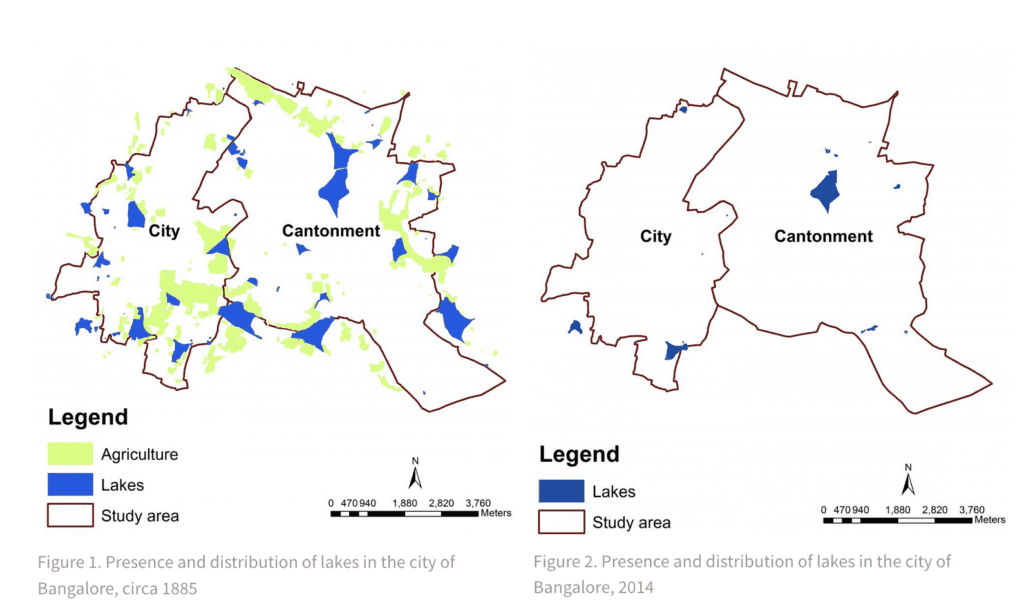

- Bengaluru’s urban cover increased 350% over a 25-year period between 1992-2017, whereas its green areas shrunk from 17% to less than 6%’.

- The WHO recommends at least 9 square metres of green space per capita, in Bengaluru, it is only 2 two square metres per capita.

Citizen Matters and Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy, in collaboration with the Bangalore International Centre (BIC), held a panel discussion on ‘Green or Gone? Development Projects and their Impact on Bengaluru’s Environment’ on February 11, 2022.

The focus of the discussion was two-fold. One, the impact of development projects on Bengaluru’s ecology. Two, the efficacy of mandated Environment Impact Assessment (EIA) processes.

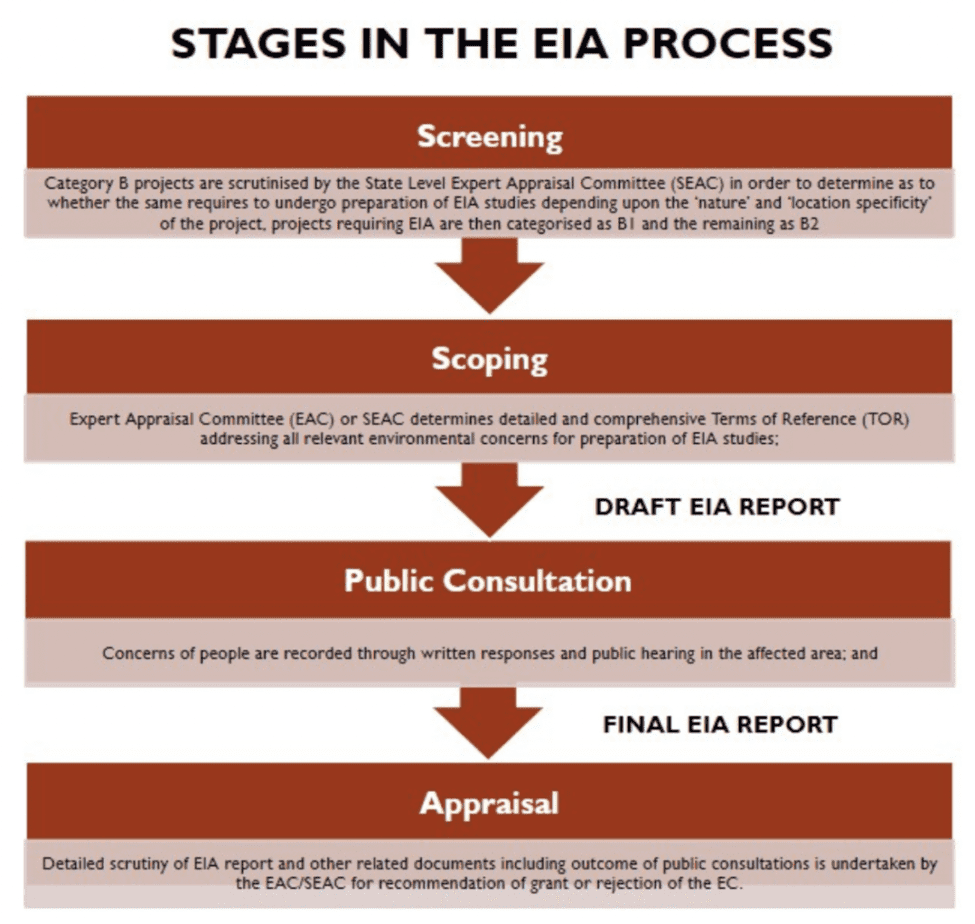

Giving an overview of the EIA process and its stages (seen in images below), Debadityo Sinha, Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy, spoke about the disappearing green and blue spaces in Bengaluru. “The roots of the city’s environmental problems emanate from its rapid expansion due to urbanisation and infrastructure development, resulting in the degradation of natural ecosystems besides putting pressure on the remaining natural assets,” said Sinha. He highlighted the vanishing lakes, grasslands and wetlands, noting how the BBMP shrugged responsibility by ‘citing lack of funds’ to develop or conserve wetlands.

Read more: Real estate developers face few hurdles in getting environment clearance

Meera K, Citizen Matters, opened the discussion by citing key figures to highlight the dismal state of Bengaluru’s ecological health and how it is all linked to Bengaluru’s climate future. One example of which was the alarming increase in land surface temperature that impacts not only rainfall patterns, flooding and water scarcity but also the physical and mental health of citizens. “The question is the foreseeable liveability of Bengaluru in the context of the climate crisis,” said Meera.

Mohan S Rao, Environmental Designer and Landscape Architect, noted a shift in the nature of the city from a “responsible, decentralised model” which saw smaller areas nestled in particular topographies, to that of large-scale developments. “The heart of the problem is institutions and departments operating in silos, without an understanding of nature and natural systems as organic and dynamic, drawing instead on outdated land use models for urban planning,” said Rao.

One example of such an outdated model that Rao noted was the lack of imagination in how open spaces are framed only as recreational spaces in the form of parks, rather than their functionality in multiple contexts such as enabling livelihood interconnections. Rao highlighted the importance of contextualising environmental regulation, keeping in mind that ecosystems serve not only ecological but also socio-cultural uses.

Journalist Bhanu Sridharan noted that while ‘nature’ is often constructed as remote, far off places like the Western Ghats, not much attention is paid to the local environment. “More of us are living in cities, or wherever we are living is going to become a city,” said Bhanu. “The physical and mental health of the urban population is linked to protecting the local environment, highlighting the need to consider urban ecology”.

Ulka Kelkar, Director, Climate Program, WRI India drew numerous connections between local and global in terms of impact of climate change. “There are limits to engineered solutions to climate adaptation given the extreme costs involved in dealing with the climate crisis,” said Ulka, pointing to the floods in Germany last year that cost them 50 billion dollars.

Ulka also spoke of the increasing industrial emissions in India with projected increases in sectors such as steel and cement. She spoke of the importance of local interventions such as rooftop solar power generation, which remain under-utilised in cities due to myriad regulatory reasons, instead of opting for massive utility-scale solar parks which create other local ramifications.

“India’s emissions will get scrutinised by the international community from next year through a ‘Biennial Transparency Report,” added Ulka. “Targets set for 2070 are not far off, which means the next decade will see myriad effects of the driving forces on tackling climate change. India has taken a lead globally with its work on disaster resilient infrastructure and it is important for India to walk the talk locally”.

Read more: Superficial studies and low transparency make Env Clearance process pointless

The EIA process

K C Jayaramu, Professor and Former Chairperson, State Environmental Impact Assessment Authority (SEIAA) shed light on the EIA process for development projects. The EIA must be conducted before and during construction and include the project’s impact on flora fauna, air, water and wildlife. He mentioned cases where SEIAA had intervened in areas like urban heritage conservation issues in Bengaluru, treatment of sewage and sullage water, buffer zones and the need to protect environment and natural resources through innovative design that focuses on conservation.

Bhanu Sridharan took up the thread speaking of her experience of how current EIA processes benefit the real sector and followed up on Meera’s opening comments on the actual working and implementation of EIA processes in Bengaluru.

“The process offers very little scrutiny in the case of smaller projects,” said Bhanu. “In the case of larger projects, the clearance process involves documentation riddled with basic factual errors, plagiarism, incorrect information on flora and fauna among other things. These issues have been documented across India and point to a lack of capacity at SEIAA to adequately scrutinise and monitor implementation of EIA rules”.

Nithin Seshadri, a member of the Koramangala 3rd block Resident Welfare Association, whose community opposed a proposed SEZ which had serious implications for the wetlands in the area, spoke of his experience in dealing with the irregularities in developers’ applications and how environmental and regulatory agencies took rubber-stamp decisions granting clearances without adequate scrutiny.

Dr Jayaramu pointed to the logistical problems that affect SEIAA, its understaffed workforce, volume of work among others . He also admitted that the quality of SEIAA’s functioning was deteriorating due to political interference and pressure.

Mohan S Rao critiqued the EIA processes and regulatory systems for not being thoughtfully designed, which resulted in a systemic failure to protect the environment. “There is a need to tackle citizen apathy and generate awareness to demand ecologically sensitive design and construction in the city,” said Rao.

Mohan S Rao critiqued the EIA processes and regulatory systems for not being thoughtfully designed, which resulted in a systemic failure to protect the environment. “There is a need to tackle citizen apathy and generate awareness to demand ecologically sensitive design and construction in the city,” said Rao.

In summary, Meera K noted lack of awareness of environmental norms amidst key stakeholders, including developers and consumer groups, as being a key challenge and re-emphasised the need to adopt a long-term and holistic vision for environmental conservation in Bengaluru.

The panel discussed the role of citizen participation, the strategies to sustain citizen pressure to protect urban ecology and heritage, and the urgent need for transparency in processes, data and use of funds in projects impacting the urban environment.

The panel also fielded questions from the audience. They looked at the question of whether a city is inherently sustainable, posed by one of the members in the audience. Panellists replied that while the city, by definition, is not inherently sustainable, people should be cognizant that they need to live in harmony with the city’s natural environment and reduce their ecological footprint.

The discussion concluded with comments from the panellists who emphasised the critical importance of decentralisation of political processes, resource management and city administration. Plus transparency from environmental regulatory agencies of their proceedings such as publishing minutes of the meetings online, the need to make city climate action plans in a scientific manner, and the need to urgently focus on implementing existing rules and regulations on protecting the urban environment.

Sneha Visakha from Vidhi Karnataka delivered the vote of thanks.

You can watch the rest of the discussion here.