Twelve-year-old Sarah vividly remembers the first stargazing trip her parents took her on, about 70 kilometers from Bengaluru, just for a glimpse of the comet Neowise. Her father, who proposed this outing, says, “When I was young, my parents would scoff at the idea of going this far just to look at the sky. Living in a city has snatched away such simple pleasures, and I had to make that effort for my little astronomer!”

Stargazers aren’t the only ones losing out due to the city lights. Studies all over the world have shown that long-term exposure to bright artificial lights can affect our body’s clock (circadian rhythm) and disrupt our sleep patterns. A 2016 study published in the journal Science Advances estimated that about 80% of the world’s population today lives in places polluted by artificial light.

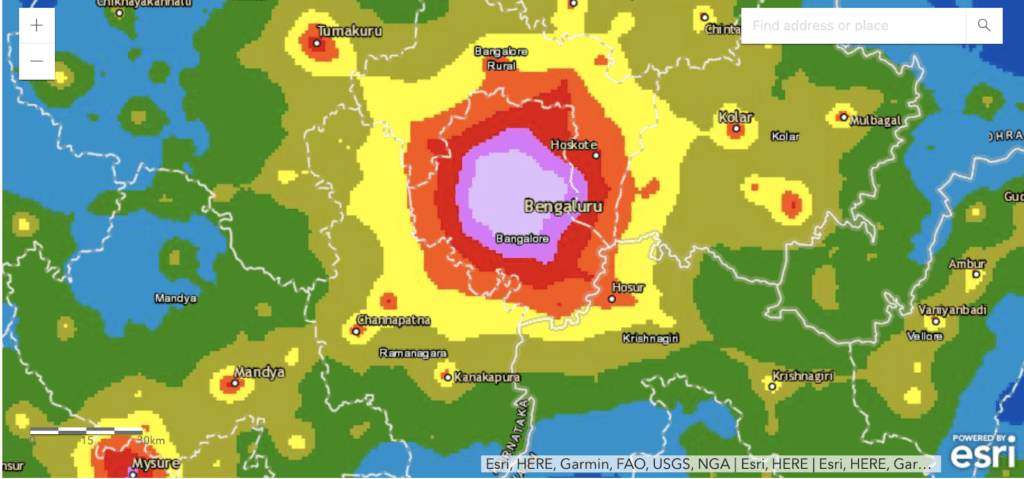

Among Indian cities, Bengaluru figures high on the Light Pollution Map, just behind Delhi and Kolkata. While humans can ‘switch off’ these lights when it gets annoying, what about the non-human residents of our cities — animals, birds and insects?

Studies from around the world indicate that light pollution affects vital activities of living beings including migration, foraging, reproduction and survival. Of special concern are insects, which are already on their way to an apocalypse.

Earlier this year, a study led by Brett Seymoure from USA’s Colorado State University called out light pollution as a major contributing factor to insect decline. As the world gets brighter by 2.2% every year, it makes sense to shine some ‘light’ on the not-so-obvious effects of light pollution on biodiversity in Bengaluru.

Night lights can kill moths, other nocturnal insects

Bengaluru is home to about 2000 species of insects, of which nocturnal insects may be the most affected by artificial lights. While moths make up the majority of these insects, those including fireflies, stick insects and termites are also active at night.

Recent studies from Europe have shown that street lights affect moths as they die of exhaustion after hovering over the light source or fall prey to predators like bats easily. There is no reason why the same detrimental effects will not happen in Indian cities. However, experts say we know very little about this.

“Light pollution no doubt affects moths and butterflies in India, as has been shown elsewhere. Unfortunately, there are no studies on the effects of light pollution on moths and crepuscular (active during twilight) butterflies in India,” said Dr Krushnamegh Kunte. Dr Krushnamegh is an associate professor at the National Centre for Biological Sciences, Bengaluru, and is affiliated with the initiative Moths of India. “We urgently need such studies to be able to manage the night light near wildlife habitats, including the woodlands inside urban areas,” he adds.

“Light pollution is a poorly-studied area, and until now there have been no systematic studies on its effects on insects in India,” agrees Dr Shashank Pathour, an entomologist and scientist at the Indian Agricultural Research Institute, New Delhi, whose research focuses on moths. “Moths are nocturnal and strongly attracted to artificial light, especially to radiations of short wavelength like ultraviolet, blue and green light.”

Animal, bird and plant species affected too

According to the International Dark Sky Association, frogs, toads, zebrafish, bees, butterflies, salmon, bats, as well as owls and many other birds are affected by light pollution. Many of these are found in and around Bengaluru.

For most creatures on Earth, the sun and the moon have been the only sources of light that acted as a compass for navigation. Until recently, that is. Dung beetles, which use the Milky Way for navigating, are known to lose their way with artificial lights. Glow worms, which communicate with their glowing bodies, face a snag in the process.

Nocturnal foragers like bats fail to recognise when it is dusk, and miss their feeding time. Artificial lights disrupt the breeding ritual of frogs and toads that sing their romantic calls in the dead of the night. Birds, including those that use natural light to time their daily and seasonal foraging, communication, reproduction and migration, are also affected by light pollution.

Increased artificial light affects the growth and development of plants too. Studies in Europe have shown that plants in urban areas retained their leaves for a long time in the fall season, and started to bud back into life early in the spring, increasing their risk of exposure to pathogens and frost.

Agricultural crops like maize and soya grow rapidly but don’t produce flowers in the presence of artificial light, thereby affecting yields. Some wild trees are known to produce fewer flower heads, attracting fewer pollinators and fewer aphids that feed on them.

Turning ‘off’ light pollution

On the bright side of things, the issue of light pollution is now starting to dominate conversations on conservation. In February this year, the Conference of the Parties to the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals, held in Gandhinagar, India, released its guidelines for combating light pollution so as to protect migratory birds, sea turtles and shore birds. Among other things, the guidelines call for assessing the environmental impact of any artificial light source, especially in areas close to wildlife habitats.

Thankfully, combating light pollution is not rocket science; it only requires a common sense approach to how we light our cities. World over, suggested recommendations include using outdoor lights that shine down and not up, regulating the amount of light with dimmers, switching off lights in buildings and homes when not in use, and using light of longer wavelengths (red or yellow colours).

The much-awaited LED streetlights of Bengaluru could do more harm to the city’s biodiversity if they are not dark-sky-friendly. Now that they are further delayed, perhaps citizens could demand better from the government?

This article is part of a series on ‘Bengaluru’s Ecosystems and Biodiversity’. This is a joint project with Mongabay India, and is supported by the Bengaluru Sustainability Forum (BSF).

While the LIGHT POLLUTION may have bad effects on the humans & insects, AT THIS HIGH-TECH BENGALURU CITY, these Lights are absolutely necessary in view of the heavy traffic on the roads, chaotic driving, road-side Romeos, platforms & pavements being occupied by the hawkers & road-side eateries, and uneven platforms with missing tiles and the like !! Somewhat dimmer lights cud be one solution ??