The recent flooding in Bengaluru made national headlines as the ‘high-tech’ IT capital of India was ground to a halt in the wake of heavy rainfall spells. The severity of the event shone the spotlight on the state of the city’s lakes, particularly the extent of encroachment, and poor waste management that have impaired the ability of Bengaluru’s water bodies and stormwater drains to act as flood buffers.

With climate change, the frequency of such extreme weather is likely to increase, underlining the need to understand the city’s complex and integral waterscape better. Lesson one, in this regard, is that lakes in the city are not isolated pools of water that rise and fall independently, unaffected by other lakes in the vicinity. The lakes in Bengaluru form what is called a cascading system – where when one lake fills up, the excess empties into the next one in the chain.

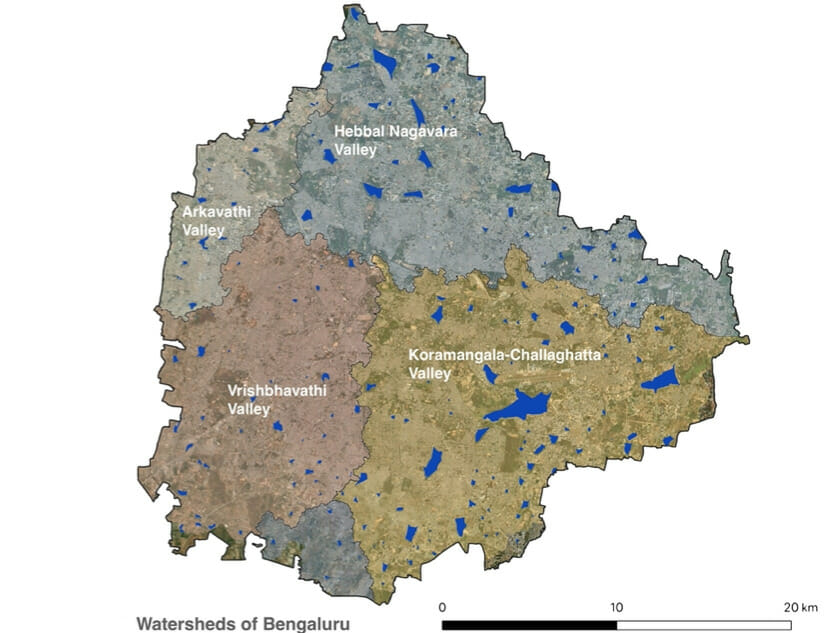

Bengaluru consists of three major valleys; the contours of which were key to shaping the city’s network of interconnected lakes over centuries.

Since at least the 6th century, settlers in what is now Bengaluru city used their knowledge of the region’s undulating terrain and direction of water flow to build tanks or lakes to store water, and connected them through stormwater drains, which are locally known as ‘rajakaluves’. The absence of a major river flowing through the city led to the need for a system that could harvest rainwater and ensure inhabitants had water for irrigation and household needs even during the peak of summer.

The network of lakes formed a system in each of these valleys, which meant that changes in even one lake have consequences on the functioning of the entire system.

But the problem now is that the city once renowned for over a thousand lakes is, at present, just left with a few hundred. Rapid urbanisation and the complex history of governance and stewardship for these lakes have resulted in them either being encroached upon, degraded or isolated from the cascading chain over time. It is important to assess the current state of water in the city to understand which areas are prone to flooding and what measures need to be taken and where.

Read more: Whom do you call to fix your lake?

Studying the cascading system in Hebbal valley

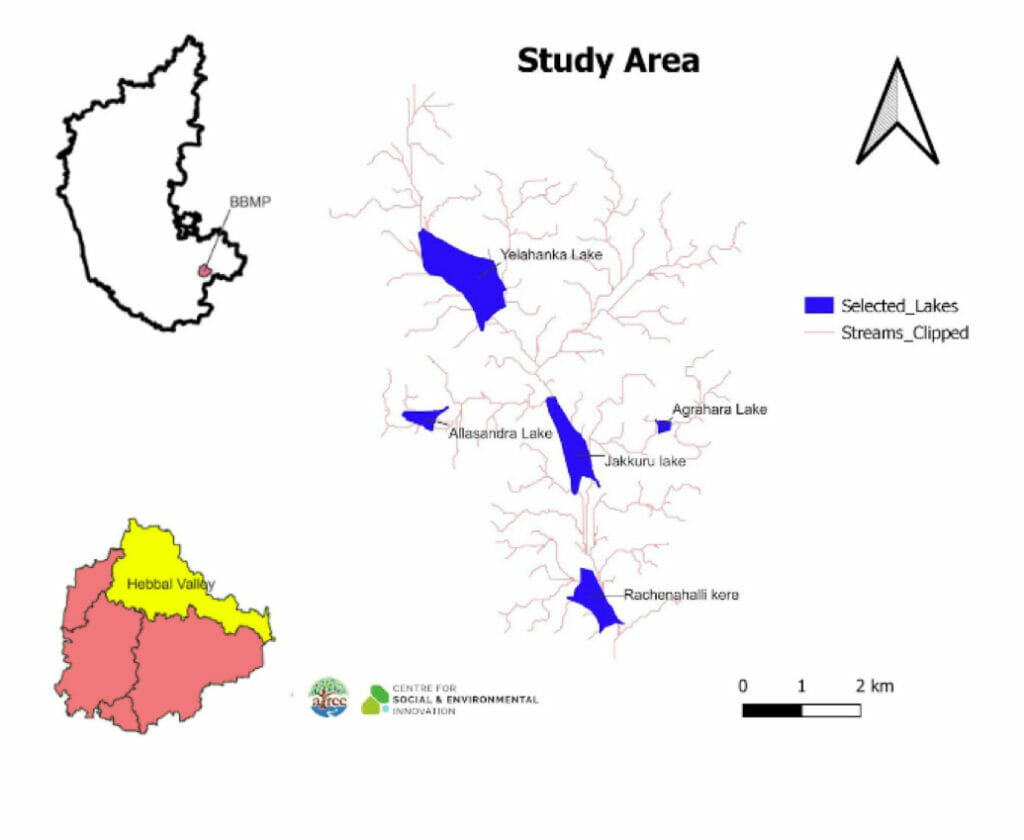

At the Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and the Environment (ATREE), we are researching this cascading system in one of the three valleys that make up Bengaluru – Hebbal – and mapped the lakes, all 72 of them. A team of two researchers and eight interns are studying how a once seamless system of water flows is impacted by new constructions. The data we collect could potentially contribute to larger urban flood modelling exercises, like that run by the Indian Institute of Science.

First, the lakes were identified using data from government bodies as well as Google Earth images. Using a Digital Elevation Model (DEM), which is a map layer that represents elevations on the terrain, we created natural stream networks for the landscape. Through this, we could identify which lake the water would flow into in the event of overflowing. After acquiring the required permits, we began our on-ground surveys to verify the data that we received from government bodies.

Inlet and outlet structures are critical for lakes to be part of a cascading system. To map these on the ground, we used a simple open-access survey application (ODK Collect) and gathered data on the structures, their location as well as images. Other features of the lakes like wetlands, islands, and sewage treatment plants were also recorded. These features also play an essential role in influencing the quality of water as well as the biodiversity around these lakes.

Read more: Surveying maps, roping in authorities and building a community for Bengaluru’s lakes

The few lakes still part of the cascading system

Our study found that only 32 of the 72 lakes in Hebbal valley still have adequate physical structures that allow the flow of water. In many of these lakes, the inlets, outlets, and stormwater drains that did exist were either broken or encroached upon by other structures. Moreover, to avoid raw sewage from flowing into these lakes, diversion drains have also been built upstream of several lakes as ad-hoc measures.

With the loss of these connections, we found that many lakes have become isolated from the system, causing them to dry out. Many of these lakes are almost completely dried up even during the peak of monsoon. Flooding is another problem in many parts here since there is no path for the water to flow and reach the next lake.

Once the lakes that are still part of the cascading system were identified, we selected a smaller part of the chain consisting of five lakes to do a more detailed study. These are: Yelahanka, Jakkur, Allalsandra, Agrahara, and Rachenahalli. Here, we are measuring both water quality and quantity.

Assessing changes in water quantity through sensors

We are installing water level sensors to understand how much water flows in and out of the lake. These ‘capacitance sensors’ measure the depth at which the sensor cable is immersed in water. The water level reading is stored in the internal non-volatile memory, which means the device will retain the data even if there is no power source, along with the timestamp.

Since the data is offline, it has to be downloaded every once in a while. We also estimate the maximum capacity of lakes either through bathymetry studies, which measures the depth of water bodies or from Detailed Project Reports of lakes. These reports are prepared whenever a lake is marked for rejuvenation work and include details on the design of the lake, financial requirements as well as stakeholders involved in project work. Given the web of institutions involved in lake restoration work, these reports are often very difficult to get access.

All this information, along with rainfall data, can be used to estimate when and how much water is going to overflow from these lakes and stormwater drains. We are working to understand how such data could serve two critically important functions: one, as early flood warning systems; and two, help planners make better lake management decisions.

Important to study water quality issues too

Bengaluru’s water problems don’t manifest as floods alone. There are issues related to pollution too. The quality of water has deteriorated to a point that mass fish kill events happen often. We are assessing the composition of water at different points in the water bodies – the inlets, outlets and the centre – and during different seasons.

The water quality data, along with the data on the amount of water flowing in and out of the lakes, can help us identify the ‘self-cleaning’ capacity of a lake. This information is key to the prioritisation of lake restoration projects and making better nutrient management plans since the magnitude of the effect of each parameter will be known. Nutrients can be managed by limiting raw sewage from entering the lakes through sewage treatment plants or by separating sewage drains from stormwater drains and ensuring raw sewage is not discharged into rajakaluves. Setting up wetlands and in-stream treatment facilities can be another approach.

Both water quantity and quality data will be used to model the cascading chain. This exercise will help us understand what changes in individual lakes can impact the entire system and thus clarify the impact of changing environmental conditions and new management decisions. For example, when government agencies decide to widen or narrow a stormwater drain; if they choose to put a diversion drain upstream of a lake; or if they release treated water into a lake – all these are actions that could cause a lake to remain full throughout the year and spill over during the monsoon. It aggravates the impact of heavy rain rather than alleviating it.

Urban planners need to be able to access high-resolution sensor data to ensure that the city becomes more resilient to climate change. Aside from acting as buffers against flooding, lakes provide a form of livelihood to fishermen and livestock owners, are a public space for recreation and are a rich habitat for flora and fauna.

When will this study be completed and what are the outcomes?