Bengaluru’s lakes have been in the news for pollution, froth, fish kill and even fire. Despite the government investing crores of rupees into reviving these lakes, and widespread citizen engagement, not much has changed. While the main reason is the lack of coordination between government departments, the absolute lack of science-based solutions is also a major gap.

In this context, Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and the Environment (ATREE) and Biome Environmental Trust (BIOME) have developed the ‘Bangalore Citizen Science Lakes Dashboard’ to share knowledge and best practices for better management of lakes. We created a series of system maps to visually represent problems at lakes and to link these with their root causes. The system maps were developed by consulting experts and studying the literature in collaboration with the NGO Janagraaha.

In the first part of this series, we look at the problem of fish and bird kills – that is, localised death of a large number of fish and birds – in Bengaluru’s lakes.

Many reported cases of fish and bird kills

In March 2018, over 150 dead fish were found floating in Puttenahalli lake, JP Nagar. The cause was believed to be high temperatures along with the discharge of raw sewage into the lake, which would’ve depleted the lake’s Dissolved Oxygen (DO) levels. The Fisheries Department recommended installing aerators to increase DO levels.

In March 2016, thousands of dead fish were found floating in Ulsoor lake. Studies proved that here too, solid waste and excess sewage had depleted DO levels. On the intervention of Ulsoor Lake RWA, the State Pollution Control Board (KSPCB) conducted a study here, and assigned specific responsibilities to different government agencies to ensure such an incident wouldn’t happen again.

In November 2018, 50-60 Indian Cormorants, a fish-eating bird species, were found dead in Kasavanahalli lake within three days. The local lake protection group contacted the Deputy Conservator of Forest (Lake division), who then sent a veterinary doctor to study the cause of death. The exact reason couldn’t be ascertained, but it was believed to have been caused by avian bird flu or a cyanobacteria bloom.

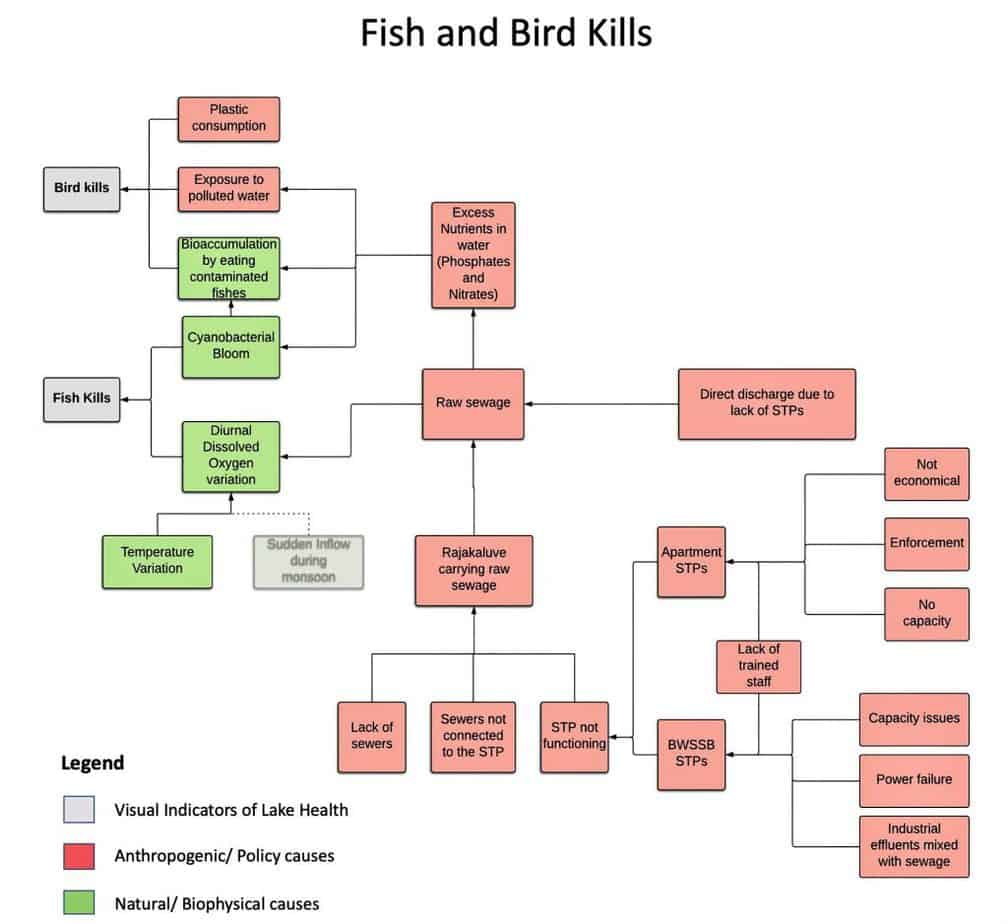

There can be various reasons for fish and bird kills. Some are listed in the system map below, but the situation in each lake may be different, and no one variable can be identified as the sole cause.

How to Read the System Map

In the system map, we start with the visual indicator of a problem (marked in grey) on the left and then trace the root cause/s of the problem step-by-step. Human causes are marked in red, and natural processes in green.

As the system map indicates, a key reason for fish and bird kills is the discharge of raw sewage (both domestic and industrial) into lakes. Raw sewage enters the lake by direct discharge, or through rajakaluves that were traditionally supposed to carry stormwater.

This happens because the city lacks sufficient sewers and sewage treatment plants (STPs) to handle its sewage, lack of planning to ensure sewers connect to STPs, and because some STPs are not functioning as they should.

Many STPs don’t function as they lack the capacity to handle the volume of sewage inflows. Power issues and lack of trained manpower are also reasons. In the case of apartment STPs specifically, high operational costs and inadequate capacity to fix malfunctions is a persistent problem.

And overall, KSPCB simply does not have the manpower for adequate, regular testing of STP effluents so as to ensure compliance with regulations.

How does raw sewage lead to fish kill though? Sewage is rich in organic matter as well as nutrients like phosphates and nitrates. These nutrients come from human waste, certain soaps and detergents. Raw sewage entering the lake can lead to nutrient pollution, which in turn can result in algal blooms in the lake. Algal blooms can deplete the lake’s DO levels in the early hours of the morning.

This is because, overnight, algae use up the oxygen that fish and other plants need to survive. (During the day oxygen levels in the water may be higher as the algae photosynthesise and release oxygen.) Oxygen levels below 4 mg/l can lead to fish kill. Bird kills, in turn, can occur when birds eat contaminated fish or toxic algae.

| What to do when you see fish or bird kill When you see bird or fish kill, report it to the lake custodian, which is usually the BBMP, or in some cases the BDA (Bangalore Development Authority), Karnataka Forest Department (KFD), Minor Irrigation Department (MI) or citizen groups that have signed an MoU with BBMP to maintain the lake. In case of fish kills, the lake custodian should be the first point of contact, who will then raise the issue with the Fisheries Department. The latter would then conduct a study on the potential causes of the fish kill. If the lake custodian is BBMP, you can contact them on 080-22660000 or contactusbbmp@gmail.com. Fisheries Department can be contacted at 080-22355129. To learn more on whom to contact, please refer to the Biome blogs on responding to fish kill and department roles. For bird kills too, the lake custodian should be the first point of contact. An autopsy will have to be conducted within 16 hours (or within 48 hours if the dead bird is stored in ice). The Institute of Animal Health and Veterinary Biologicals can also be contacted to conduct the autopsy. They are located in Hebbal and can be contacted on 080-23411502 or info@iahvb.com. Refer to the Biome blog here on what to do when you see bird kill. |

How to prevent fish and bird kills in the first place?

Lake groups in Bengaluru have been able to bring communities together to protect lakes. Some solutions to fish and bird kills involve infrastructural improvements where the community must work with various civic agencies.

Primarily, the discharge of raw sewage into lakes should be stopped. This means having better infrastructure to treat raw sewage, having separate drains for stormwater and sewage, and ensuring raw sewage is not discharged into rajakaluves.

But non-point sources of pollutants – where there are several diffuse sources of pollutants rather than singular ones like an STP or rajakaluve – can be harder to rectify. Even the treated sewage entering lakes tend to be high in nutrients.

Hence additional mechanisms may be needed to “scrub” the nutrients, such as wetland plants that can absorb these. These solutions, however, can be hard to implement as they require large capital, coordination between agencies, and stricter law enforcement.

Lake custodians and lake groups themselves can improve DO levels in the lake temporarily, by adding aerators and floating wetlands. These and other methods such as bio enzymes and bokashi balls have been tried at different lakes, but the functionality of each method is still being understood. Ideally, lake groups should systematically collect and report data on the efficacy of these experiments so as to facilitate cross-learning across lake groups.

Citizens can also help improve the lake’s health quality by visiting and monitoring the lake. Just observing and reporting sewage ingress to local lake groups and government authorities is a step forward.

Lake groups can also help prevent the dumping of solid waste and sludge into the lake with higher fencing or by appointing home guards. Education programmes that explain the link between solid waste and lakes may help people make better choices regarding solid waste management, and prevent waste being dumped into water bodies as well.

[Sanjana Alex, Shubha Ramachandran and Suma Rao are part of Biome Environmental Trust (BIOME). BIOME has been set up with the aim to conduct research, public education, practice-to-policy bridging and policy advocacy in the areas of land-use and land-use planning, energy, water and sanitation.

Veena Srinivasan is part of Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and the Environment (ATREE), a global non-profit organisation which generates interdisciplinary knowledge to inform policy and practice towards conservation and sustainability.]