Bengaluru, once known as the ‘City of Lakes’, has made national and international headlines as the ‘City of Burning Lakes‘. Lakes in Bengaluru have caught fire several times – mostly at Bellandur lake, but also in other parts of the city. The fire burns for hours, polluting the air with smoke and creating a public health hazard.

| Bellandur Lake, the city’s largest lake, has burst into flames many times in the recent past. The first instance was in May 2015, and then again in August 2016, February 2017, and January 2018. The 2018 fire lasted 30 hours, with smoke engulfing the neighbourhood. To solve the issues at Bellandur, Varthur, and Agara lakes, the National Green Tribunal (NGT) set up a committee of experts headed by Justice Santosh Hegde. As per the NGT order, BDA, the lake’s custodian, is responsible for de-weeding and desilting the lake. BDA started work in 2019. All inflow into the lake has been stopped, and desilting has been on since this April. However, some environmentalists have raised concerns about heavy metal pollution in the silt and its safe disposal, and have called for a study before this is undertaken. |

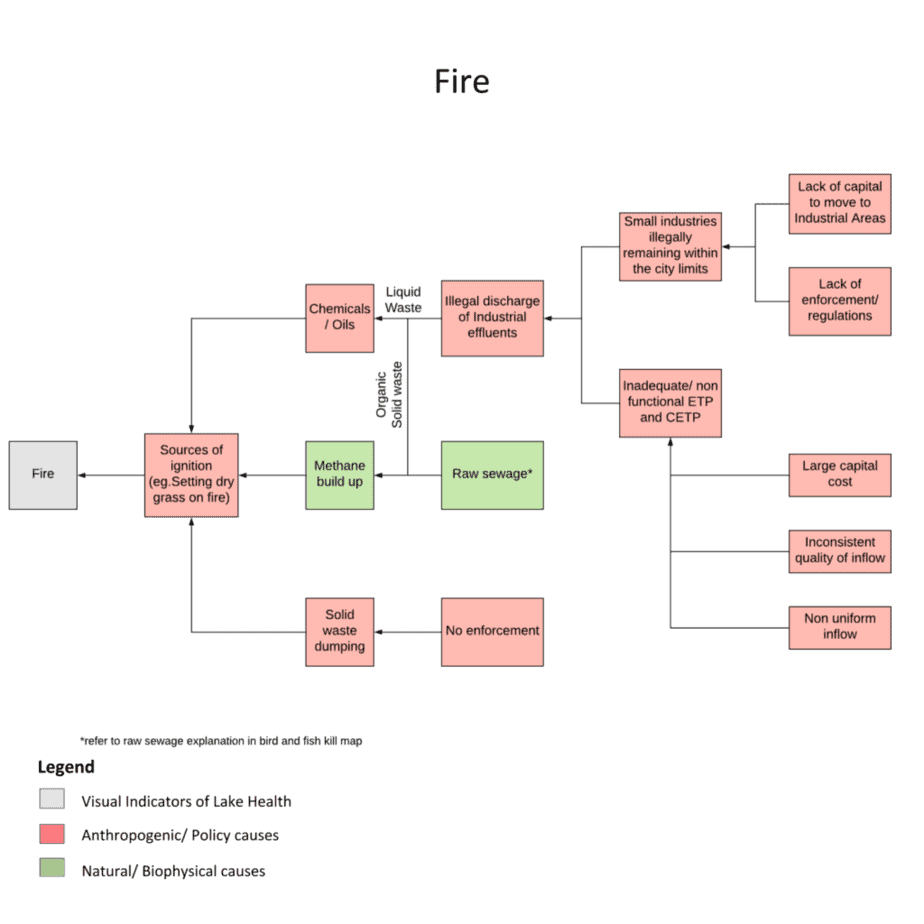

To better understand the problems with Bengaluru’s lakes, we created a series of lake system maps to visually represent these problems and their root causes. The first article in this series depicted the root causes for bird and fish kills. In this article, we look at the problem of fire in Bengaluru’s lakes.

Reading the system map

Scientists are still exploring the root causes of these fires. There are several theories that have some credence. All of these ultimately point to the presence of untreated domestic sewage, industrial effluents and solid waste being discharged into the lakes.

Excess raw sewage and industrial effluents high in organic content entering the lake can create anaerobic conditions for the build-up of gases. One such gas is methane, which is highly flammable.

To understand how raw sewage affects Bengaluru’s lakes, we need to first understand the traditional drainage system that was meant to hold and distribute stormwater throughout the city. Bengaluru sits on a ridge 900 m above sea level and has three major valleys – Vrishabhavathi Valley, Koramangala-Challaghatta Valley (KC Valley), and Hebbal Valley. Water from the top of the ridge flows into the three valleys, and each valley in turn has its own series of lakes. The lakes were created such that water from an upstream lake would overflow into a downstream lake through stormwater drains.

Bengaluru generates more than 1400 MLD (Million Litres per Day) of raw sewage but only has the capacity to treat 40% of it. The other 60% of untreated sewage finds its way into lakes through the stormwater drain system. Learn more about domestic sewage discharge in the first system map.

In addition to raw sewage, industrial effluents that are illegally discharged into the lake can also contain toxic chemicals and oils. Oils can form an insoluble layer on the water’s surface, making it highly flammable.

Industrial effluents get discharged into lakes due to:

- Lack of adequate effluent treatment plants (ETPs) or common effluent treatment plants (CETPs).

- Non-functional ETPs and CETPs : These treatment plants are designed to treat a certain quantity and quality of effluents, and cannot function well when this is inconsistent.

- Small-scale industries that do not have their own ETPs need to send their effluents to CETPs. Many a time, the CETPs are located far away, making pipelines non-feasible. This means effluents need to be transported by tankers to the CETPs regularly.

- The capital and O&M cost of ETPs and CETPs are extremely high.

Similarly, solid waste from households as well as construction and demolition waste dumped into a lake can form a thick layer on the surface, blocking the diffusion of oxygen from the environment into the lake. This too could create anaerobic conditions that could lead to methane build-up.

Research by ATREE and the UK Centre for Ecology and Hydrology has found that the methane level in Bellandur lake was more than 1000 times the levels seen in less polluted lakes, and is likely an important contributor to the lake catching fire regularly.

Bellandur and Varthur lakes are at the bottom of the Varthur lake series, and are the last two lakes in the KC valley catchment. Hence, the two lakes receive a lot of the diverted sewage from upstream lakes. It is estimated that 40% of the city’s sewage is discharged into Bellandur’s catchment area alone every day. (Water that flows out of the KC valley catchment feeds into the Dakshina Pinakini and eventually flows into Tamil Nadu, where the water is used by farmers for agricultural purposes.)

A spark caused by high summer temperatures, burning of solid waste or dry grass near the lake, or a lit cigarette butt/matchstick thrown nearby can ignite the combustible liquids or gases in such lakes.

Steps to take when you see fire at a lake

The first step is to contact the Fire Department, dial 101, and if possible inform your lake custodian.

How to prevent lakes catching fire

- Identifying hotspots of pollution in the catchment – such as industrial clusters, residential/commercial areas – that are not connected by the underground drainage network.

- Monitoring water quality downstream of the hotspots. The water quality parameters should be selected based on the activities in the hotspots. For example, downstream of industrial clusters, in addition to organic and nutrient contaminants, trace metals, oil and grease should be monitored. Water quality data will help assess the effectiveness of an intervention on water quality.

- Civic agencies such as BWSSB and BBMP should prevent raw sewage and industrial effluents from entering lakes.

- Top-down approach: Setting up large-scale sewage and effluent treatment plants. Ensuring efficient operations by a) treating industrial and domestic effluents separately, b) regular monitoring of the treated effluent c) deployment of skilled personnel at the treatment plants and d) regular supply of electricity for smooth operations of these systems

- Bottom-up approach: At present, raw sewage is diverted from the lake, but diverting it from the upstream lake to the downstream lake just passes the problem from one area to another. Decentralised treatment systems should be deployed to treat sewage locally.

- Fence the lake boundary to prevent solid waste from being dumped near the lake.

- Lake custodian or lake groups can create awareness programmes on better solid waste management, and educate citizens on potential causes of fires such as burning of solid waste near the lake or throwing match sticks/cigarette butts near dry grass, especially during summers.

- Citizens can be vigilant and report illegal solid waste dumping or discharge of raw sewage/industrial effluents into the lake, to the lake custodian.

This Lake System Map series is created by Bangalore Citizen Science Lakes Dashboard. It is an initiative by the Center for Social and Environmental Innovation at Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and the Environment (ATREE) and Biome Environmental Trust (BIOME) to share knowledge and best practices for better management of lakes. The system maps were developed by consulting experts in collaboration with Janagraaha.

Resources

- Report by the Energy and Wetlands Research Group, IISc, on Rejuvenation Blueprint for Lakes in Vrishabhavathi Valley: It addresses short-term and long-term solutions to improve lake water quality.

- A rejuvenation report submitted by Namma Bengaluru Foundation.

[Shubha Ramachandran and Suma Rao are part of Biome Environmental Trust (BIOME). BIOME has been set up with the aim to conduct research, public education, practice-to-policy bridging and policy advocacy in the areas of land-use and land-use planning, energy, water and sanitation.

Sanjana Alex, Priyanka Jamwal, Shashank Palur and Veena Srinivasan are part of Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and the Environment (ATREE), a global non-profit organisation which generates interdisciplinary knowledge to inform policy and practice towards conservation and sustainability.]

Comments: