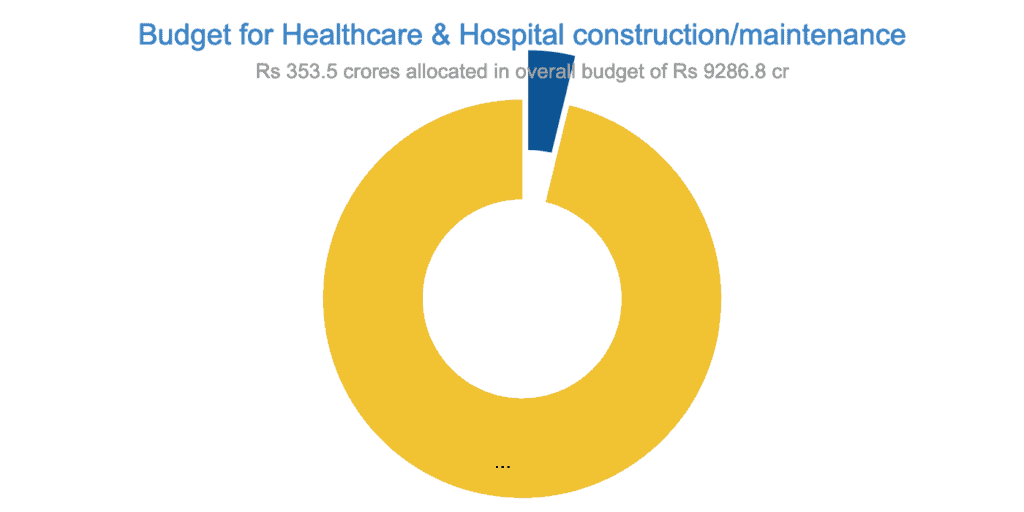

The most important lesson for the Covid first wave was the urgent need to strengthen the state’s public health systems and infrastructure. But the current year’s budgets of both the state government and the city government ignores this need. In fact, the state’s 2021-22 budget has been criticised for its low priority to strengthening the public healthcare system overall.

As of now, all attention inevitably is on managing the Covid second wave. “Rs 50 cr is earmarked towards ‘natural calamities’, that is, Covid management”, says Thulasi Maddineni, Special Commissioner (Finance) at BBMP. The BBMP had spent Rs 90 crore on this last year.

“All the big-ticket expenses, such as equipping hospitals with oxygen concentrators, gas oxygen pipelines, testing, contact tracing, etc, will come from the state government,” says Maddineni. “There is no shortage of funds from the government. We will use our funds for expenses like maintenance of offices, phone bills etc”.

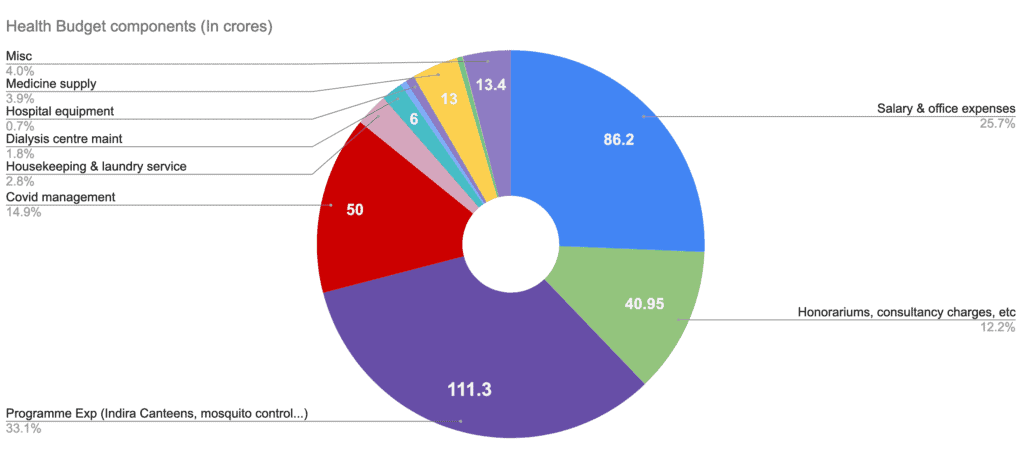

Of the remaining Rs 285 crore of the health department budget, Rs 111 crore goes towards various other programmes like food supply through Indira Canteens (Rs 80 cr), mosquito and street dog control, stents for heart patients etc. Around Rs 86 cr goes for salaries and office expenses and payment of honorariums and incentives.

Which leave littles money available to maintain and improve BBMP’s own public healthcare facilities – procuring and maintaining hospital equipment (Rs 2.5 cr), drug supply for health centres (Rs 13 cr), maintenance of dialysis centres (Rs 6 cr), etc.

In addition to the Rs 336 cr allocation to the health department, the budget also allocates around Rs 17 cr to BBMP’s Public Works Department to build and maintain hospitals and health centres.

Read More: What BBMP’s budget holds for the ordinary Bengalurean

In short: Some progress, major challenges remain

- Low budget allocations point to low priority to improving public health care systems

- Severe shortage of ASHA (Accredited Social Health Activist) and ANM (Auxiliary Nurse Midwife) staff who reach out to the community.

- BBMP’s previously derelict PHCs have been upgraded with more doctors, lab facilities, lab technicians, pharmacists, etc to manage Covid

- BBMP has been building more general hospitals. However, getting them operational depends on state government sanctioning posts of doctors, nurses, and other support staff.

- BBMP will work with private medical colleges for doctors in referral hospitals. A model MoU is being prepared for this.

- In recent health camps, it was found that more people are vulnerable to Covid due to uncontrolled comorbidities like diabetes or hypertension.

- There is no acknowledgment that primary healthcare is best provided locally, and best monitored by the local government

Shortage of community workers

The allocation for health does not address the severe shortage of ASHA (Accredited Social Health Activist) and ANM (Auxiliary Nurse Midwife) staff who reach out to the community. Till a few years ago, BBMP had an effective network of link workers who reached out to communities. But this system was dismantled when these workers were moved to the Solid Waste Management department.

The adverse effect of that move is being felt now. “BBMP needs manpower for contact tracing, testing, identifying cases through syndromic approach, vaccinations, etc,” says Dr Giridhar Babu, co-chairman of BBMP’s Covid-19 Task Force. “ASHAs and ANMs are supposed to do this, but their numbers are not sufficient to cater to even one-fiftieth of Bengaluru’s requirements. Currently everything is a stop-gap arrangement.”

According to Dr Girdhar, rural areas have one ASHA per 1000 of the population, and one ANM per 5000 people. They work at the community level – ASHA volunteers educate people and bring them to the health centres, while ANMs are formally trained in ante-natal care and vaccinations. “On my request, former BBMP Commissioner Manjunath Prasad did move files to recruit ANMs at the required rate of one per 5000 of population,” says Dr Giridhar. “The Urban Development Department (UDD) too gave its approval, but has not identified the funds to be used for this. So even the existing vacancies for ANM posts have not been filled. The cost of hiring ASHAs/ANMs now would not be more than Rs 100 crore per year, and the BBMP itself can easily include this in its budget”.

According to an officer at BBMP’s health department, currently, there are only 1100 ASHAs and 440 ANMs for Bengaluru’s population of around 1.27 crores! This translates to an average of one ASHA for nearly 11,500 people, and one ANM for every 29,000 of population.

PHCs upgraded, but other health facilities ignored

The pandemic had one positive fallout. BBMP’s previously derelict PHCs have been upgraded with more doctors, lab facilities, lab technicians, pharmacists, etc, and are playing an important role in Covid management. But at the cost of BBMP’s other facilities—maternity homes, referral homes, and general hospitals. According to the BBMP Health Department website, there are 26 maternity homes, six referral hospitals, and one functional general hospital, the JJR Nagar General Hospital. The other main hospitals in the city – Victoria, Bowring, general hospitals in Jayanagar, Yelahanka, etc, all come under the state government.

BBMP’s maternity homes and the referral hospitals provide only maternity and ante-natal care. “Maternity homes can refer complicated cases to referral hospitals which don’t provide any other service,” said a health department official. “Also, JJR Nagar General Hospital is not functioning to full capacity. As a general hospital, it should at least provide 24X7 services, but currently, it works only from 9 am to 4 pm, mainly because of shortage of support staff and equipment.” For example, there is a surgeon in the general hospital, but no proper operation theatre or trained staff like operation theatre assistants. Hence no surgeries happen here. “The hospital now works like a big PHC”.

Read more: Battle-weary Covid warriors dreading second wave

Hospitals without staff

BBMP has been building more general hospitals, but they won’t be able to function until the state government sanctions posts of doctors, nurses and other support staff. A dysfunctional BBMP hospital system means citizens rely on state government hospitals for even minor problems, and those facilities get overcrowded.

“The referral system in a rural setup is that the PHC refers cases to the CHC (Community Health Centre), above it is a taluk hospital, and then a district hospital,” said the BBMP official. “But in Bengaluru, cases from the PHC – even a fever or minor surgery – are directly referred to the state government’s general hospitals which are actually like district hospitals”. This also means patients have to pay out of pocket to travel to a tertiary facility, with potential loss of daily wages.

“There should at least be one BBMP general hospital per assembly constituency that’s well-equipped; they can least function as CHCs, so that PHCs can refer cases to them,” added the official. “This is critical for Covid management too. BBMP’s referral hospitals and general hospitals should work 24X7 during Covid. If a person tests Covid-positive in a PHC, he should be referred to these hospitals instead of the state hospitals. The doctors there can do triage and decide if the patient should be sent for home isolation or to another facility. Also, say a Covid patient in home isolation develops breathlessness due to panic, he can go the BBMP hospital instead of an overcrowded state hospital”.

Thulasi Maddineni agrees. “New hospital buildings are coming up, but there are not enough sanctioned posts,” says Maddineni. “During Covid, we will work with private medical colleges so that there are doctors in the referral hospitals.” Her budget speech mentioned that a model MoU was being prepared for this.

More people vulnerable to Covid

This brings us back full circle— why the government needs to invest in public healthcare in the long term, so as to manage a future pandemic or disaster. “Even the first point of contact – that is, PHCs – should be able to offer all services – staff, outreach workers, drugs, lab testing, ambulances, etc,” says Dr Sylvia Karpagam, a public health expert. “PHCs should be able to treat most of the common diseases and do minor surgeries”.

The BBMP should identify why the system was unable to cope during the first wave, and plan its budget so as to plug those gaps, argues Dr Sylvia. For example, last year, people with cancer or HIV, or senior citizens with ailments couldn’t get medicines due to financial crunch or being turned away by hospitals. “In recent health camps, we found that many senior citizens now have uncontrolled diabetes or hypertension because of this. If BBMP facilities were more prepared, they would have been able to fill this gap. Now, more people are vulnerable to Covid due to uncontrolled comorbidities”.

Dr Sylvia also calls for a rethink on government reimbursing private hospitals during Covid. “In many private hospitals, asymptomatic patients were occupying beds, this was not rational or ethical. This sector is so unregulated and public funds are going to it, while there is no investment in public facilities”.

Read More: A hundred years ago, Bengaluru beat the plague; here’s how

Possible solutions

But given that currently, healthcare is almost entirely under the state government, and BBMP only has a supervisory role and is heavily dependent on the state government for funds, how can BBMP revamp the system? Especially when a large portion of allocations for healthcare are for specific programmes such as the HIV programme.

“Providing efficient health services in an urban area is very expensive,” points out Madhusudhan B V Rao of the Centre for Budget and Policy Studies. “BBMP can try different models—-offer primary care for different specialisations at a lower cost (say Rs 150-200) than in private hospitals. Or instead of having one PHC per ward, have one with all services—including mobile services—for a larger area. BBMP also needs to collect user data, so that it can know which users have to be subsidised and who can pay”.

But such options are not even being discussed. “There is no acknowledgement that primary healthcare is best provided locally, and best monitored by the local government,” adds Madhusudhan. “There should political space for councillors to discuss healthcare needs in their area and demand funds from the state and centre, and citizens have to work with councillors for this.”