Bengaluru is increasingly becoming a city with more roads and flyovers, and with less spaces for public interaction or informal encounters. As in other Indian cities, here too, administrators imagine a city that meets global standards of urban form and infrastructure. Whereas, at the neighbourhood level, people continue to nurture and sustain spaces like ashwath kattes (peepul tree shrines), informally generating community spaces. And these spaces – which assimilate the rural within the urban – survive even as government agencies have been rampantly usurping public spaces for various projects.

There are two competing processes in city-making – one, from above, generated by administrators; and the other, from below, based on how people informally inhabit public spaces. The case of ashwath kattes prompts us to ask: Can these two processes work together? Can there be a more people-centred approach to city planning that retains our traditional informal spaces?

Read more: Citizens take pledge to save trees from felling

Ashwath kattes are religious, social, ecological spaces

The Peepul tree (known as the Ashvattha in Sanskrit literature, or Bodhi tree in Buddhist contexts) is a type of Fig tree (Ficus Religiosa). And the platform around the tree is the ‘katte’. In Bengaluru, ashwath kattes are commonly found adjoining Mariamman temples.

Many ashwath kattes in Bengaluru are hundreds of years old. Ashwath kattes are also linked to the city’s growth – for example, after the plague epidemic in 1898, an extension was given to Basavanagudi layout, and Mariamman temples along with ashwath kattes became very popular there (as the goddess was believed to protect people from diseases like plague).

Ecologists consider the peepul tree as one of the ‘keystone’ species. These are species crucial in maintaining the diversity of their ecological communities. In India, the ecological significance of the peepul tree is embedded in daily rituals and religious ceremonies.

In the last few years, we, at Everyday City Lab, have documented 75 ashwath kattes in Bengaluru with the support of citizen volunteers. We have learnt that people come to ashwath kattes to not just pray, but also to socialise.

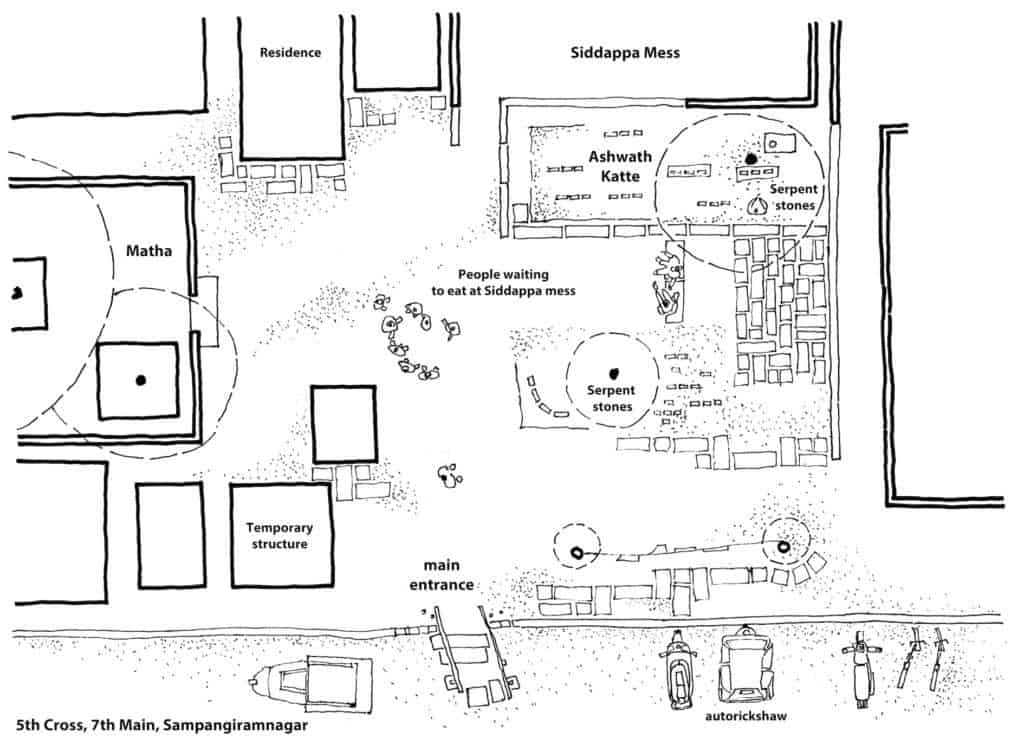

While a few kattes in the city are fenced and used exclusively for religious worship, the majority are open spaces where people socialise and engage in various activities, where informal vendors sell their wares, and children play. Some like the Siddappa Mess katte in Sampangiramnagar (where a mess adjoins the katte) are secular spaces too, fostering interactions between visitors to the temple and the mess. It is not uncommon to see a local resident, a flower vendor, a tea vendor and a group of retired men spend their time together at an ashwath katte, exchanging views or sharing experiences.

So far, our key lessons from closely observing ashwath kattes are:

- It is a place where religion and ecology intersect.

- The peepul tree has a wide canopy and provides ample shade for people to sit, to interact or to sell.

- Ashwath katte is a place of gathering for both men and women where social relationships are nurtured and strengthened between people of different backgrounds.

- The interactions of people at the ashwath katte help create collective memory and social capital. And higher the collective memory, lesser the chances of government encroaching upon these public spaces.

Read more: New green movement in city to focus on native trees

Urban planning in India

In the post-independence period, urban planning in India was largely influenced by the ideas of western architects like Corbusier and Louis Kahn. Nehru had invited Corbusier to propose a plan for the new city of Chandigarh.

As James Scott, the political scientist and anthropologist has pointed out, Corbusier drew up these plans the same way he had planned cities like Central Paris and Buenos Aires earlier – as if no city existed there before, with no reference to the urban history or traditions of the place. Corbusier planned Chandigarh with the same geometry, and affinity for order and efficiency, and with little connect to the city’s past or its present.

In the following years, Indian planners and administrators continued to nurture this approach that planned the city from a distance, making the everyday life of the city invisible and therefore non-existent.

Is there an alternative?

The random gathering of people on the street during a festival; a disorderly platform around the peepul tree; the clustering of push-cart vendors – should it all be cleaned up for a formal plaza with stone benches neatly arranged around a water fountain? We believe it is possible to develop an Indian idiom of urban design if we understand how our existing public spaces work – who comes there, how long they stay, what is the nature of interactions it harbours, and so on. Our planning processes could integrate the existing ashwath kattes into the changing urban fabric of older neighbourhoods.

Patrick Geddes, the biologist and sociologist who drew a series of plans for Indian cities in 1915, advocated an ecological theory of town planning. He argued for an urban planning approach where the work of officials and planners would be associated with fruit growers and gardeners, where the focus would be on nature rather than on engineering. He appreciated local customs and the role of festivals in Indian cities in order to conceptualise urban space for the future.

Taking notice of an ashwath katte in Thanjavur in 1915, Geddes had remarked that this street element should be repeated a thousandfold. Today, having researched the ashwath katte for a few years, we too believe ashwath kattes should be a part of our urban fabric, that can work as small, public spaces in every neighbourhood.

We believe that at the city level, Bengaluru needs to find its own relevant and local solutions to the problems of urban growth. At present, there is no mechanism to resolve the conflict between the urban planning criteria the government relies on and everyday life at the neighbourhood level.

If our existing cities are seen to have developed through historical chance, can there be a middle ground for designing our future city – which rests partly on the logic of how we know a city to work, and partly on the reasoning that our urban spaces are transforming based on the changing social, cultural and economic processes that make the city liveable?

Our online book on ashwath kattes is now available for free download here. You can also watch our film on ashwath kattes on YouTube.

In kannada they are called aralikatte. Ashwatha is a different tree than Peepal.

That’s true, Manjula. In Kannada, it is called the arali katte.

However, the Ashvattha is Sanskrit term for the Peepul tree. There is a reference here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ashvattha

And, another reference can be found here: David L.Haberman. People Trees:Worship of Trees in Northern India. Oxford University Press. pp. 73–74.”

In the Bhagavadgeeta, Krishna says “ O, Arjuna, of……, and of trees, I am the ASHWATTHA “. This ancient belief rooted in the fabric of India is one reason why the ASHWATTHA is considered sacred. ASHWATTHA Naaraayana is one aspect of Naarayana, a primal deity. My grandfather taught Sanskrit a hundred years ago under a huge old ASHWATTHA near Holenarsipur. So

did many others over millennia.