Prime Minister Narendra Modi has been extremely keen to promote Indian culture as a virtuous lifestyle both within the country and abroad. Ancient Indian traditions of Yoga and Ayurveda are being pushed by the Government. Modi’s gifts to foreign dignitaries are often thoughtful symbols of historical events and the crafts of India. It therefore comes as a shock, that the same Government that deservedly places such a high value on our ancient and profound heritage, has proposed a dilution of the Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Sites and Remains Act (AMASR Act)of 1958 to allow large-scale construction in the vicinity of nationally protected monuments.

A precursor of the present Act, the Ancient Monuments Preservation Act was first promulgated more than a century ago in 1904. The British Government in recognition of the tremendous archaeological treasures of India decided to accord them protection and entrusted the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) with the preservation and protection of these amazing monuments, buildings, structures and remains.

The 1904 Act was replaced by the present Act in 1958. As per this amended Act every monument would be protected with a buffer zone of 100 meters in all directions, called the “prohibited area.” No new construction of any kind, either public or private would be allowed here.

Beyond that there is a “regulated area” of 200 metres, where construction is not prohibited, but must be approved by the National Monuments Authority, a new body created to ensure that construction and other activities in the vicinity of ancient monuments is not detrimental to the monument itself.

But now, the Union Cabinet chaired by the Prime Minister has approved the introduction of the Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Sites Remains (Amendment) Bill, 2017 which amends Section 20A of the existing Act to allow any Department or Office of the Central Government to carry out public works in the prohibited area after obtaining permission from the Central Government.

A government release announcing the amendment explicitly says that restrictions on new construction within the “prohibited area” adversely impacts various public works and developmental projects of the Central Government. This amendment will thus pave the way for certain constructions, limited strictly to public works and projects essential to the people, within the prohibited area and benefit the public at large.

The rationale behind restrictions

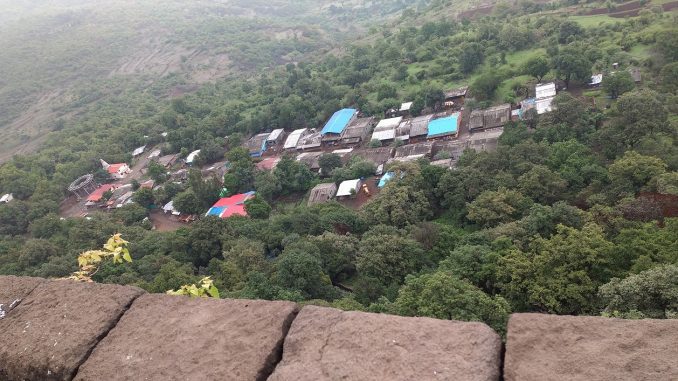

Unfortunately, most of our 3686 nationally protected monuments, some of which are absolutely unique in the world, are not in great shape. They suffer not only from neglect and gradual disrepair, but sadly are also being encroached upon, ruining the ambience and aesthetics of these magnificent structures.

In Hyderabad for example, unauthorised structures and encroachments have sprung up at and around historic monuments in the city, such as Golconda Fort, Charminar and Qutb Shahi Tombs, leading the state government to consider a special task force to clear these and seek UNESCO recognition for the monuments.

The boundaries of the prohibited and regulated areas under the existing AMASR Act (1958) can in fact be increased beyond their default limits, if an ancient monument requires a larger protection area.

Keeping in mind the unique nature of each monument, the Act also provides for monument-specific “heritage bye laws” to be made by an expert heritage body, such as INTACH. The bye-laws would ensure that the aesthetics and function of the monuments and its surroundings are not affected. As an example, Jantar Mantar, the astronomical instruments built in 1724, require that buildings in the vicinity should be built such that they do not block the sun rays from reaching the structures.

However, hardly any of the monuments have well designed and informative displays or visitor centres, such as those that one sees very routinely in other countries. The significance of the monuments is therefore not understood by the public at large. No wonder then that most people, other than archaeologists and historians, see these monuments as a nuisance, something that impedes “development” rather than as something that needs to be preserved and cherished.

The same attitude is now reflected in the Government’s stance, leading to a proposal to dilute the Act in order to allow public works, or construction undertaken by the Central Government inside the prohibited area.

A real and present threat

That this misguided proposal may spell doom for many of these monuments is obvious. Public works undertaken by the Central Government are usually extremely large projects – railway lines, ports, airports, highways etc – the construction of which is bound to have an enormous impact on some of the more fragile monuments.

In May 2015, a crane positioned within the Walled City in Jaipur to facilitate the ongoing underground construction work for the Jaipur Metro came crashing down on the 250-year-old Naval Kishore temple and the Udai Singh Haveli, causing damage to both structures. Clearly, therefore, an exemption for public works poses grave risks to the monuments near which such work shall be carried out.

On the other hand, the 100-metre boundary around any protected monument could be easily avoided with better planning. A classic example is the Delhi Metro, which was constructed even with this restriction in place, in the NCR which incidentally has 174 nationally protected monuments, more than any other metropolitan area in the country.

The direct amendment of law by the government without any consideration of such carefully planned and sustainable alternatives, raises certain questions.

What is the value we place on the environment and our built and natural heritage?

What is the value of the lives of the poor and marginalized (the tribals)?

Do we want development at any cost, even at the cost of those who cannot speak or stand up for themselves?

Many of these monuments have stood the test of time, but will they succumb now to mindless human activity?

It is really up to us as a nation and as a society to decide.

Luckily some prominent historians and policy-makers have spoken up against this move by the Government. Ordinary citizens are lending their support to the issue by signing a petition launched by the Pune-based NGO Parisar. At this stage, one can only hope that good sense will eventually prevail.

Very good .. govt should remove 100 meter law for all private and public… Further dustbin ruin should be removed .

It is a nuisance, the law must be amended from 100 meters to jut 5 meters like many countries. People living in the vicinity of these useless monuments are suffering, OR their properties should be purchased at a prime price by the Govt and include and make the effected properties part of these useless garbage monuments, if they are really so important.