Bengaluru is not typically imagined to be a hotspot of biodiversity, and the urban biodiversity here often gets missed in conversations about the environment. The city’s water bodies and green spaces, apart from being recreational spaces, are a home to biodiversity as well as a source of livelihood for many citizens.

In this set of illustrations, we examine the components of Bengaluru’s lakes, and get a glimpse of what lies beneath the concrete layers and dense human population in our city.

Every artwork has elements of household and construction waste that the artist found in her neighbourhood in Bengaluru. Look closely and see if you can spot them.

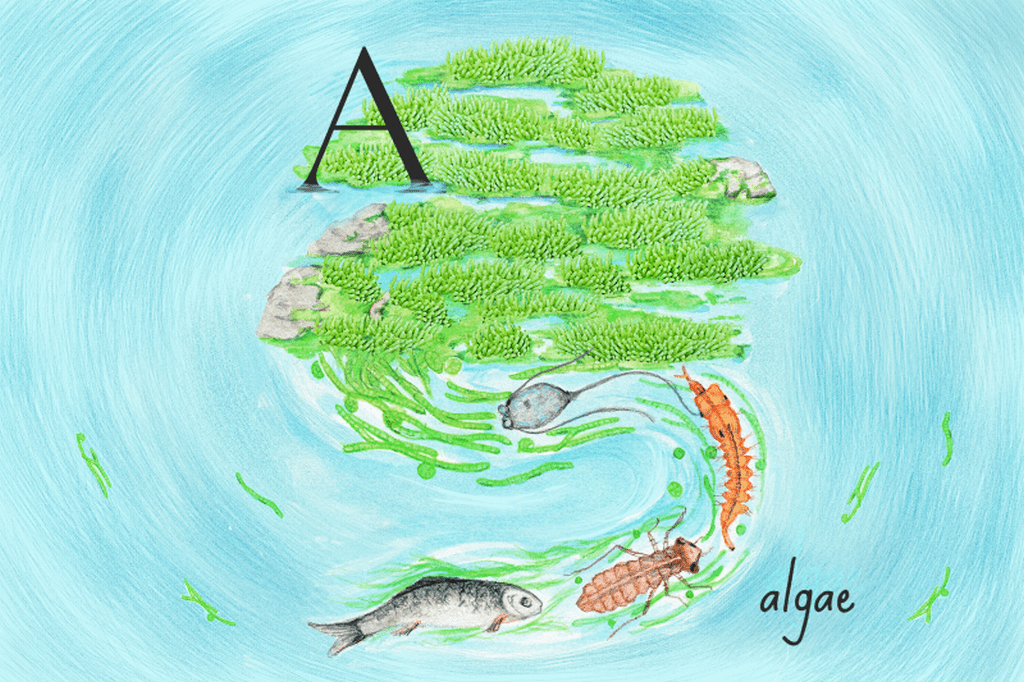

Algae

Why are many lakes in Bengaluru green? It is because they are blanketed by microscopic plants that contain chlorophyll, called algae. But are they good or bad for the lakes?

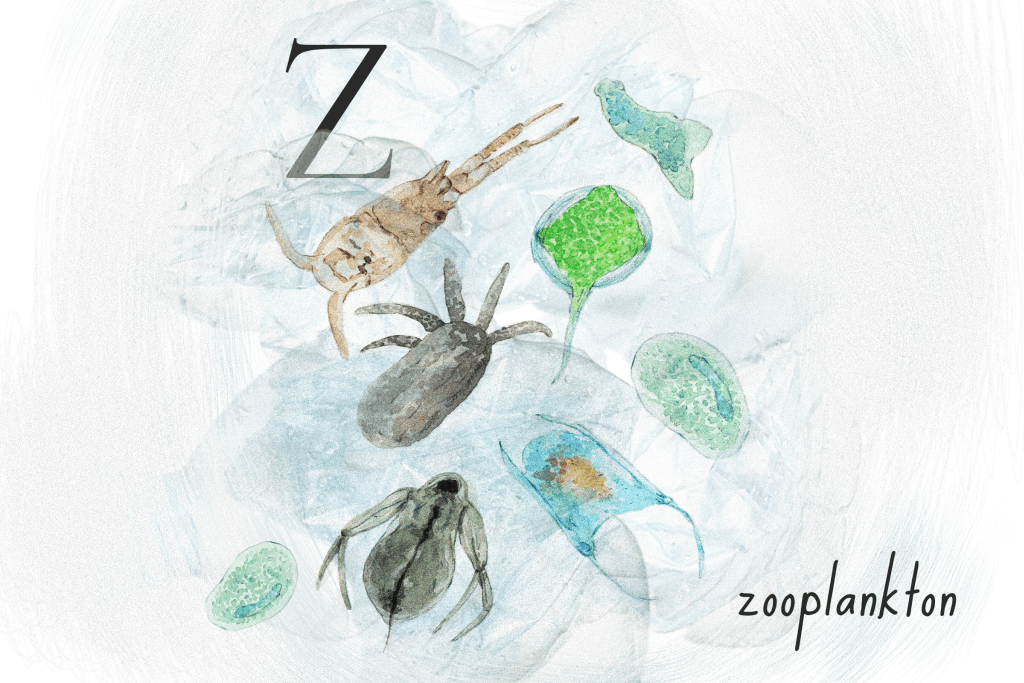

Fixers of carbon, generators of biomass and inconspicuous primary producers in the ecosystem – algae are vital for healthy lakes. These microorganisms convert water and carbon dioxide to sugar, through the process of photosynthesis. This generates oxygen as a by-product. Zooplankton, small fish and other aquatic creatures consume algae, launching the magical process of the food cycle.

But too much of a good thing can also be a bad thing. Excess algae, especially the harmful types, can be detrimental to the lake, indicating pollution and high amounts of nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus which cause eutrophication. The overgrowth of algae can also cause ‘dead zones’ in the lakes, where aquatic life cannot survive because of insufficient oxygen.

In Bengaluru, with the discharge of industrial waste and untreated sewage, algal blooms (rapid increase in the population of algae) occur. The water then gets polluted, discoloured, clogged, and gives out a certain odour.

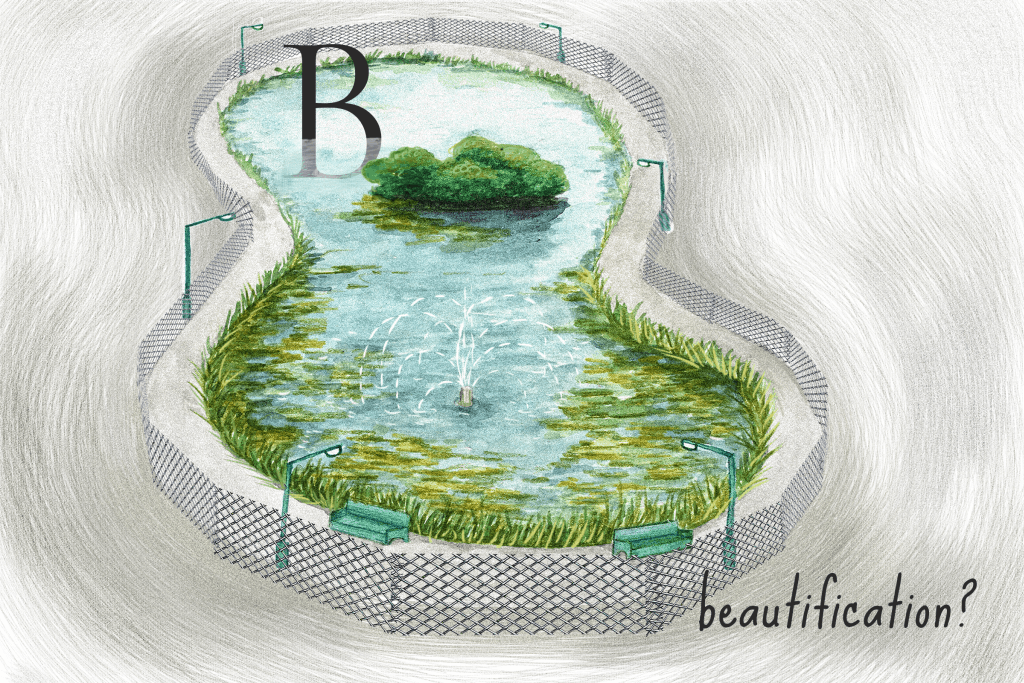

Beautification?

A lake’s beauty comes from the biodiversity it hosts, its calm waters and views. But in recent times, ‘beautification’ in the urban context is associated with artificial structures and concretisation. Landscaping, boating, paved pathways and restricted entry through ticketing are some of the elements of the brick-and-mortar beautification of Bengaluru’s lakes, while activists call for use of the funds for regular rejuvenation actions like desilting, de-weeding and sewage management.

Environmental activists argue that instead of focusing solely on superficial beautification of water bodies, the plan should be to restore them and maintain them. Because, by simply beautifying lakes, development projects end up shrinking their size by destroying the wetlands surrounding the lake, which has a deleterious impact on lake health. Excess concretisation, and planting of non-native trees rather than the native species typically found around the lake, affects biodiversity.

Coracle

Round, light-weight boats – coracles – are a reminder of Bengaluru of yore. Before a joyride on a coracle became a tourist attraction, these boats were widely used by fisherfolk for traditional and sustainable fishing. Fishing communities used the coracle to spread nets and harvest fish. The practice is less popular now as urbanisation has changed the landscape and fishing practices have been modified too, though fishermen still use coracles made from synthetic materials instead of natural materials. The coracle remains a symbol of the journey of Bengaluru lakes from fishing hotspots to recreational sites.

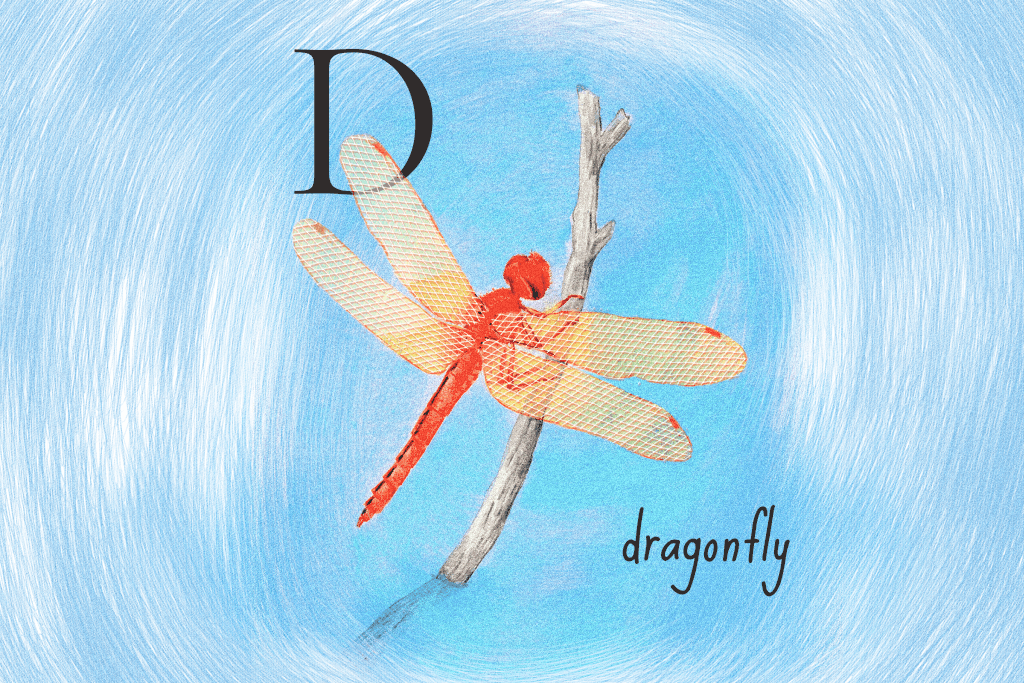

Dragonfly

Buzzing around Bengaluru lakes, dragonflies are often on a hunt for insects on the lake. These speedy fliers spend most of their life near water bodies and are part of the lake ecosystem in Bengaluru. The larvae live in water, and the adults are terrestrial and find their food by the water.

Millions of dragonflies migrate thousands of kilometres across the sea each year, from southern India to Africa. Biologists claim this could be the longest migration of any insect. Their presence is very important for humans too. Being aerial predators, they catch unwanted insects like mosquitoes and feed on them. They also catch midges, butterflies, moths and bees.

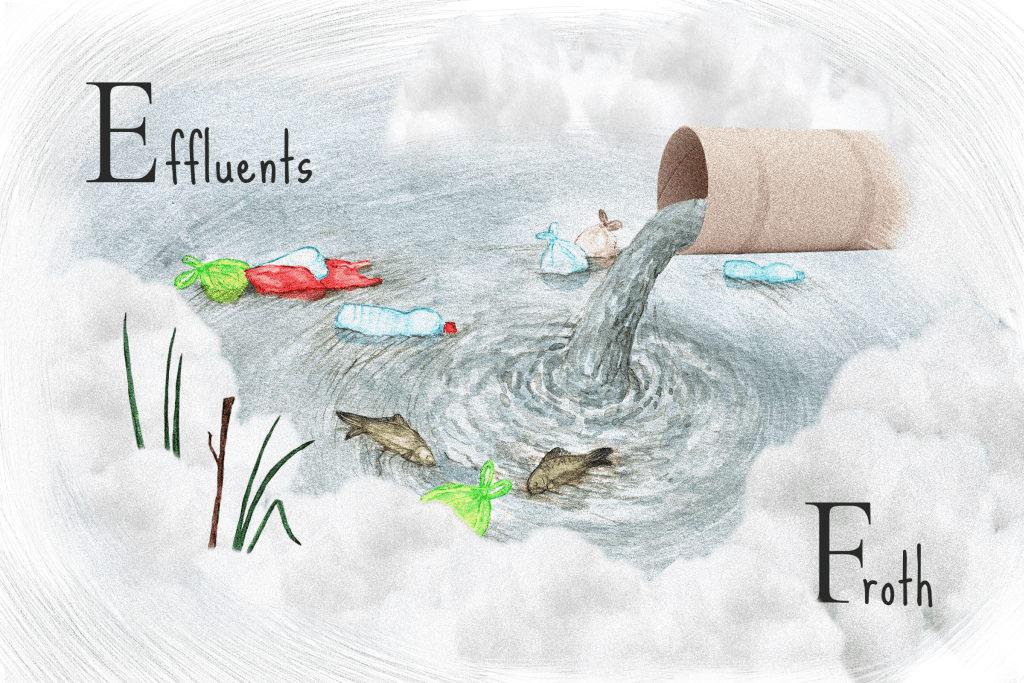

Effluents and Froth

Effluent is wastewater containing a high amount of toxins that flows out of factories, industries or sewer plants, directly into water bodies. Effluent discharge into the freshwater ecosystems like lakes, affects the water, reducing its oxygen content and making it unusable. It also affects the soil that is fed by this toxic water. The poor water and soil quality in turn is harmful to plant and animal life that survive on them.

Effluents are also one of the elements of froth – bubbles of water that form a white layer on lakes. Due to effluents, non-biodegradable detergents and other toxins present in the lake, the lakes belch out froth. Bengaluru’s Bellandur lake, infamous for its pollution, has been found covered with a huge amount of smelly froth. The fluffy white frothy layer on a lake is actually a sign that the lake is unhealthy and needs immediate restoration attempts.

Groundwater

Groundwater is the water present beneath the Earth’s surface. In Bengaluru, one of Asia’s fastest growing cities, groundwater is not available in abundance to meet the water demand. Bengaluru’s annual average rainfall is 970 mm. Well, that seems sufficient to meet our needs! Yes, but in many parts of the city the groundwater is contaminated due to sewage, industrial waste and soil pollution, making it unusable/unsafe.

Conserving groundwater needs action by both the citizens and the government, who together need to ensure that groundwater recharge is carried out at scale across the city.

Hello

Public spaces are what give character to a city. Bengaluru has evolved to become synonymous with lakes because of how successfully people utilise the space. Lakes in Bengaluru are reminders of a childhood spent in the company of nature. The greenery, the water and the biodiversity in and around the water source, people in their calmest moods, make the time spent by lakes a relaxing affair. The lake is a place of many ‘Hellos’ – familiar hellos and new hellos. Here, friendships are formed, much needed alone time is sought, communities come together, and outdoor recreation is pursued.

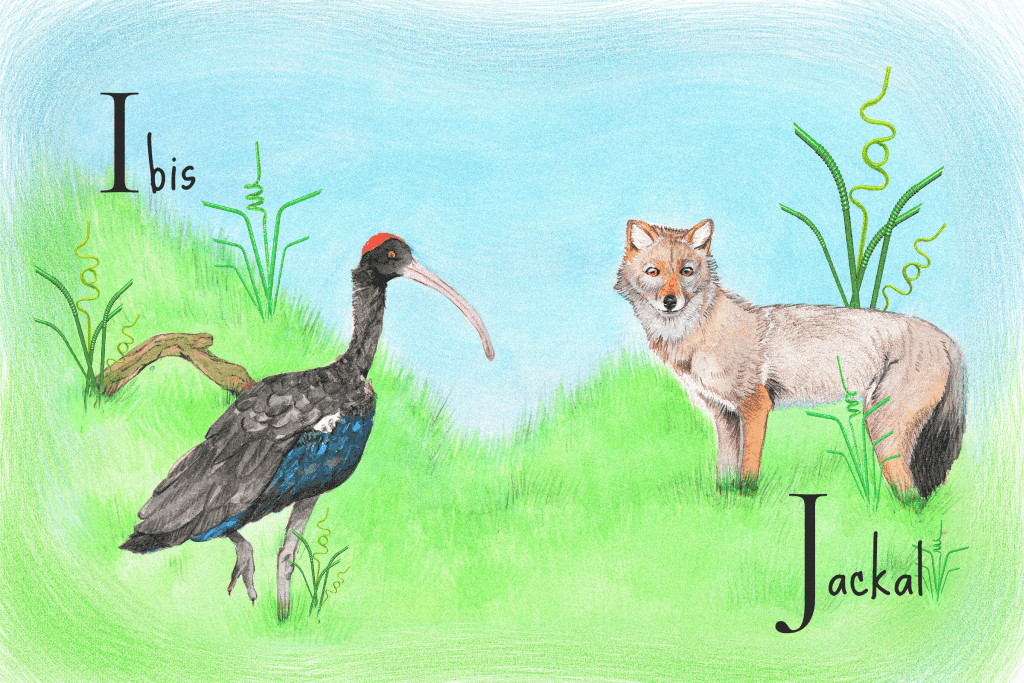

Ibis and Jackal

With its long, downward-curved bill, the ibis is easily recognisable. It usually inhabits wetlands and plains. The red-naped ibis (left) is a regular at Bengaluru’s lakes. The wetlands are also home to the black-headed ibis and the glossy ibis.

Waterbirds like cattle egrets, pond herons, the Eurasian spoonbill, spot-billed pelicans, cormorants and painted storks are other birds who depend on Bengaluru’s lakes, offering many sights for birding enthusiasts and citizen scientists.

The lakes of Bengaluru once also hosted jackals in huge numbers. The shrinking green spaces and water bodies have led to their numbers dwindling as well. Jackals are primarily scavengers, although they are also known to prey on birds, rodents and other small animals. Snakes, jungle cats, mongooses and slender lorises are some of the other urban wild residents of Bengaluru.

Kere

Kere (ಕೆರೆ) is ‘lake’ in Kannada. Since the city does not have a perennial river running nearby, and the water dependency lies on Cauvery which is also very far, keres in Bengaluru are an integral part of the culture, economy and history. Some of the popular lakes are Sankey tank, Madivala tank, Bellandur lake, Chele kere, Hebbal lake, Ulsoor lake, Varthur kere, Jakkur lake, Akshayanagara kere and Benniganahalli tank. Wetlands like kere are productive and biodiverse ecosystems within themselves, but remain unappreciated in spite of the important role they play and their numerous benefits.

You will occasionally hear the Kannada term kere habba which means the celebration of the lakes. Such celebrations are now a way to spread more awareness about the conservation of lakes, and bring the community together to be actively involved.

The city also has a number of smaller water bodies – gokattes (defined as water bodies between 1 and 3 acre) and kuntes (defined as water bodies less than 1 acre) – which have been around for centuries. Kattes and kuntes are important for water security, biodiversity and flood prevention. According to a 2018 inventory in the Environmental Management and Policy Research Institute report, 57.5% of gokattes and 75% of kuntes of Bengaluru have disappeared.

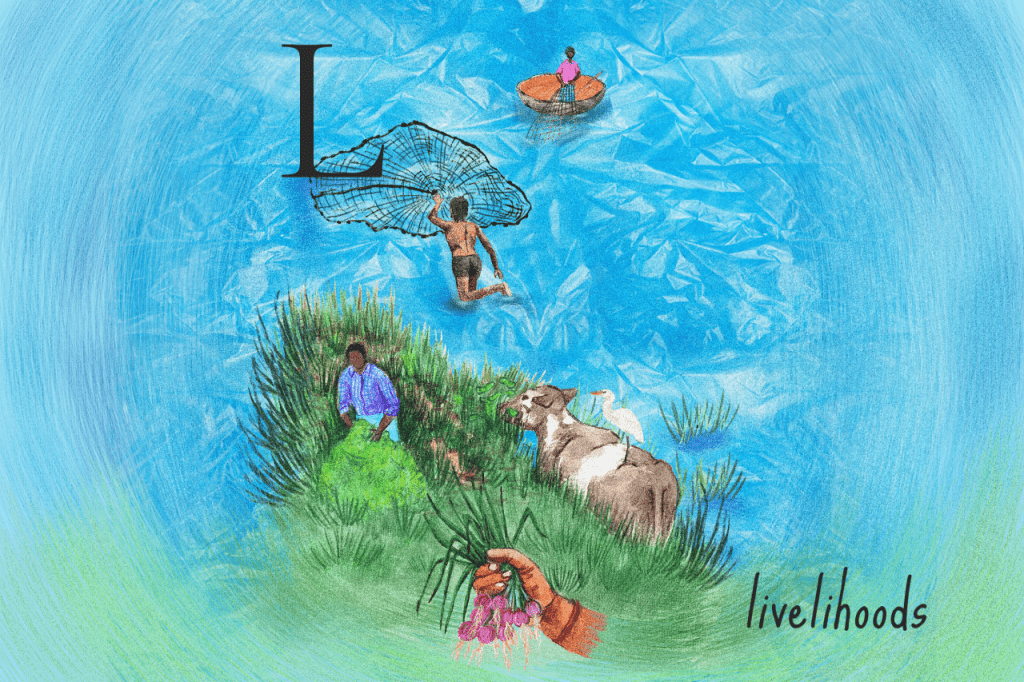

Livelihoods

What does a healthy lake look like? Apart from an impressively balanced ecosystem, the waterbody also provides livelihood opportunities for citizens. With proper rejuvenation of lakes, livelihoods can be protected too.

Farmers, foragers, fisherfolk and artisans depend on the natural resources from healthy lakes. Livestock can graze in the grass of healthy lakes, fishes thrive, plants and trees provide the means of income for farmers and foragers, artisans collect clay and mud for crafts. There are so many people who depend directly or indirectly on lakes for their livelihood. The revival of lakes, thus, must factor in the protection of livelihoods too.

Microclimate

Do you feel like the city is getting hotter and hotter each year? It’s partly because of a phenomenon called Urban Heat Island (UHI). An ever-expanding, burgeoning city like Bengaluru is home to many residential areas, offices, industries and recreational spaces. When we keep replacing natural spaces like green covers, lakes and other wetlands with dense concrete, glass and steel structures, the temperatures in the city become warmer than the surrounding areas.

Microclimate is the climate of a small, specific area. Lakes play an important role in managing the micro-climate of areas. They maintain atmospheric temperatures and reduce the impact of UHI effect.

Nesting

Some lakes of Bengaluru are havens for nesting waterbirds. Resident birds and summer visitors nest in the greenery on the fringes, or on the vegetation or mini islands in the middle of the lakes. The birds depend on the smaller animals, insects and plants around the wetland to feed their chicks. Grey-headed swamphen, pond heron, cormorant, little grebe, spot-billed pelican, and painted stork are some of the birds that use the lakes of Bengaluru to nest.

Rampant urbanisation, and the loss of surrounding trees in particular, threatens nesting habitats.

Oxygen

Just as we need oxygen in the atmosphere to breathe, fish and some other organisms need oxygen in water to breathe. The oxygen from the atmosphere dissolves in the water and this is called Dissolved Oxygen (DO). Adequate DO is a good measure of a lake’s quality. If the DO in a lake drops, the aquatic life suffers, shrinking the biodiversity of the area. The discharge of waste into the water can deplete DO content, killing fish and other aquatic life.

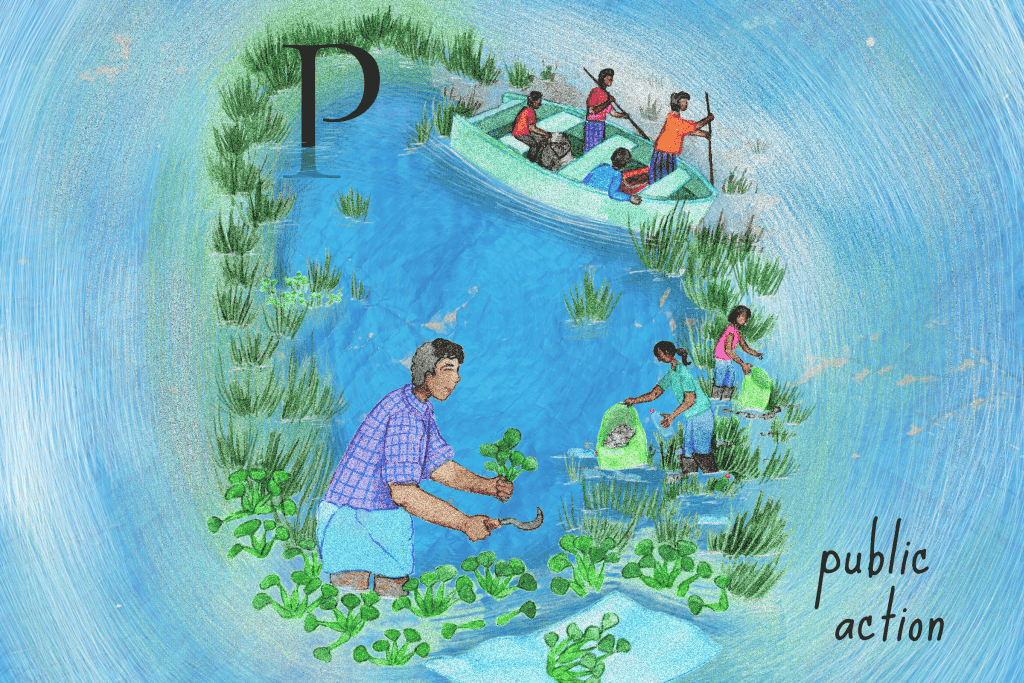

Public action

The quality of a public space has a direct impact on the lives of people and the way they feel. Effective, sustained public action has made a huge difference in the revival of many damaged lakes in Bengaluru. The story of Jakkur lake set an example for the success of inclusive rejuvenation projects. The fisherfolk became the crucial stakeholders and took charge to better the lake. Working together can help restore many lakes to their original state and also help many people protect their livelihoods.

Quiet

In a bustling city like Bengaluru, the tanks and lakes offer momentary quietness. The calm waters, the excited and curious birds, and the trees and plants that cushion the area from the urban din, provide relief from noise pollution in the busy metro.

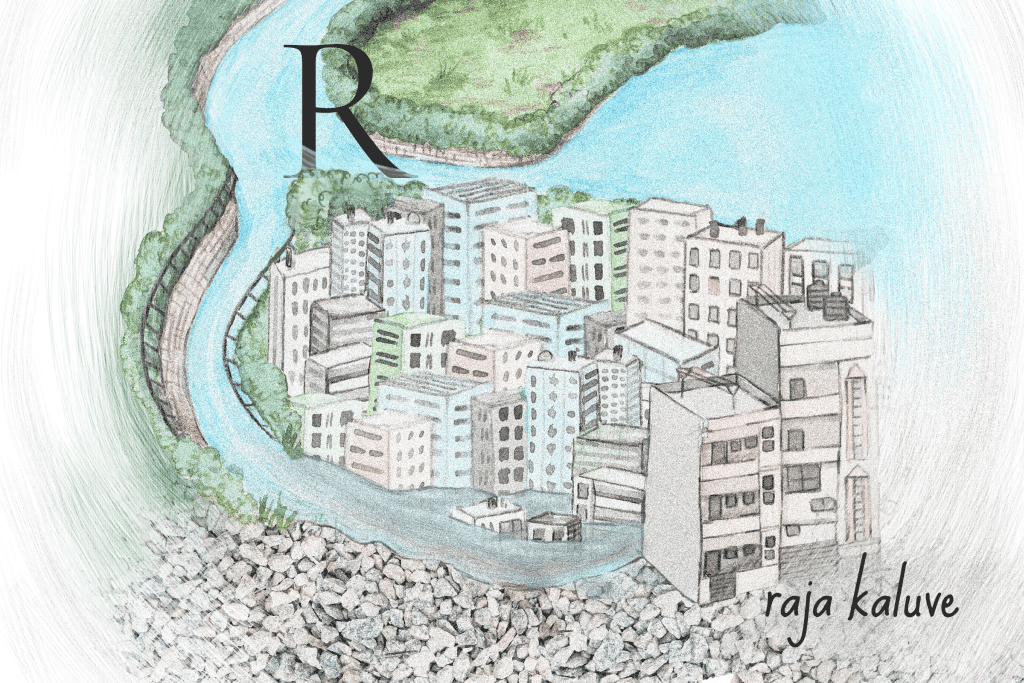

Raja kaluve

Most lakes in Bengaluru are artificial lakes, called tanks. They have been built and maintained for several centuries now, and receive water from rains. The lakes are linked by a network of natural or human-made channels or storm water drains, known as raja kaluves, which transport surplus water from higher elevation lakes to lower elevation lakes. Encroachments, dumping of waste or diversion of these channels cause overflow, and can lead to flooding during rains.

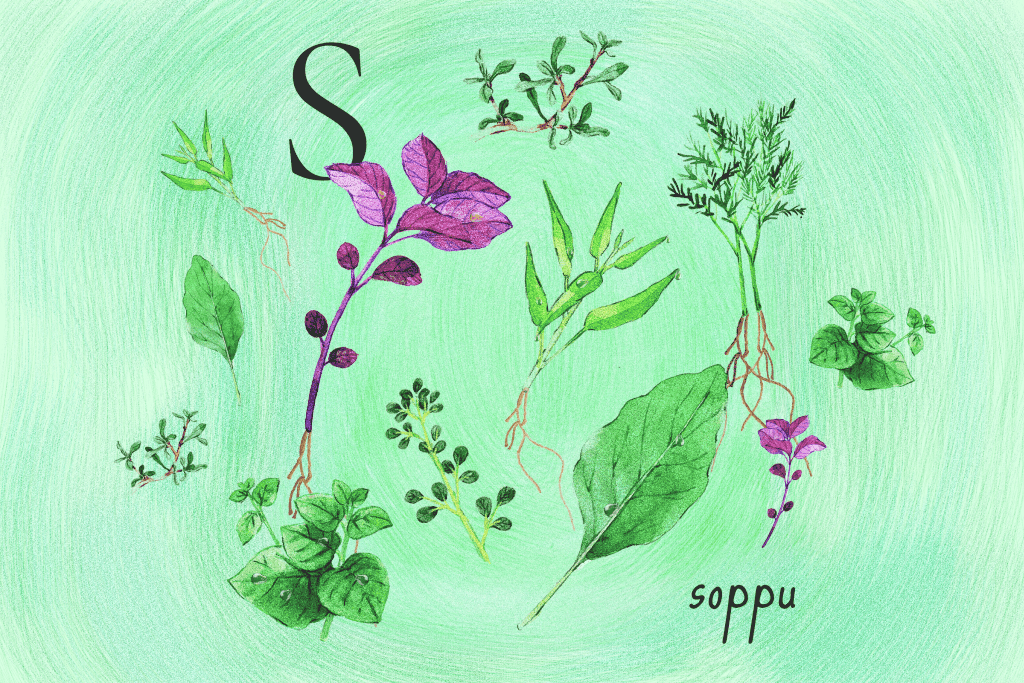

Soppu

Soppu are different types of green leafy vegetables and are an integral part of Karnataka’s cuisine. Soppu are found in the natural growth around the lakes and wetlands in Bengaluru, and many foragers and farmers collect the greens to sell them. Healthy lakes encourage healthy greens and support livelihoods. These greens are also locally consumed and form an important part of the nutrition requirements for poorer families. They are also known to have some medicinal uses.

Sewage and garbage dumping has deteriorated much of Bengaluru’s lakes, adversely impacting biodiversity and means of income for many. At lakes that have been revived or where sewage has been diverted away, there is once again the opportunity for income for those who gather and sell soppu.

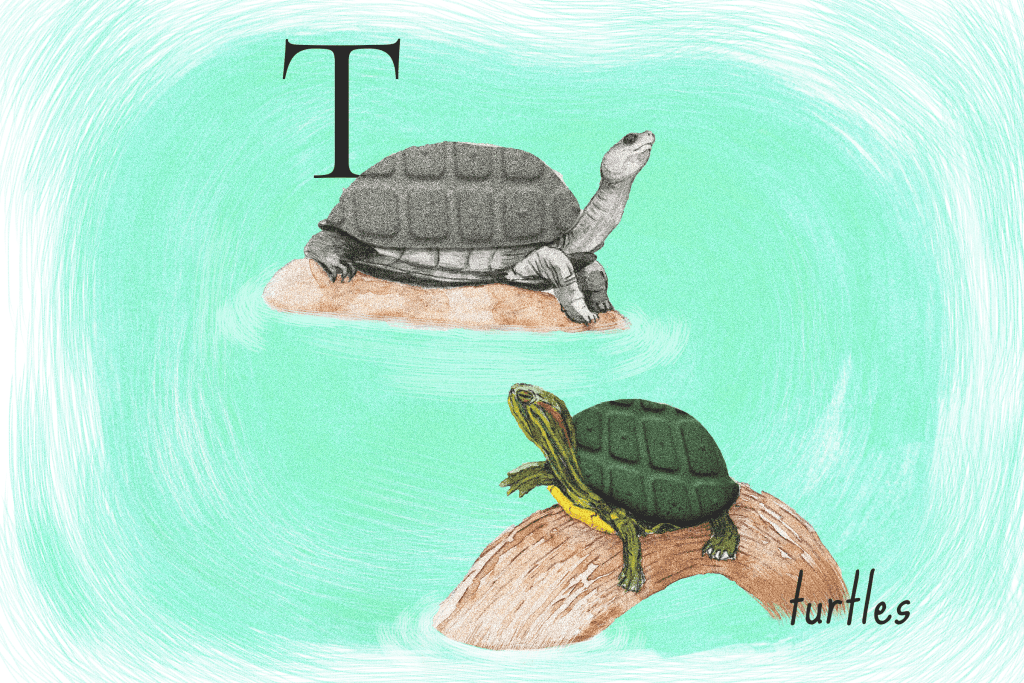

Turtles

India has around 29 native species of freshwater turtles and tortoises. Bengaluru’s lakes are home to some of them, such as the Indian black turtle (Melanochelys trijuga) (top), which is a native species found in the city’s lakes. Turtles are important to maintain a healthy lake ecosystem.

But not all turtles are healthy for these lakes. The red-eared slider turtle (Trachemys scripta elegans), found in the city’s lakes too, is an invasive species. The exotic and popular pet is often released into the wild by pet owners and it becomes a threat to the native turtles by competing for food and nesting space, and even spreading diseases. With more than 50% of freshwater turtles threatened with extinction, conserving lake habitats is vital.

Urbanisation

Bengaluru is the third most populous city in India. With the growth of the IT sector and expansion of the city, natural spaces have shrunk. Urbanisation, though inevitable and needed in the process of modernisation, comes at the cost of many natural resources.

There is ample evidence of encroachment and pollution of waterbodies due to excessive urbanisation. Economic growth has had a major impact on the ecosystem in Bengaluru as green spaces have turned into building complexes, and lakes have shrunk in numbers and sizes. The lakes either get built on or are used as dumping grounds for waste and construction debris, killing the lake. Now, both government and non-governmental organisations are working to improve the conditions of the lakes in Bengaluru.

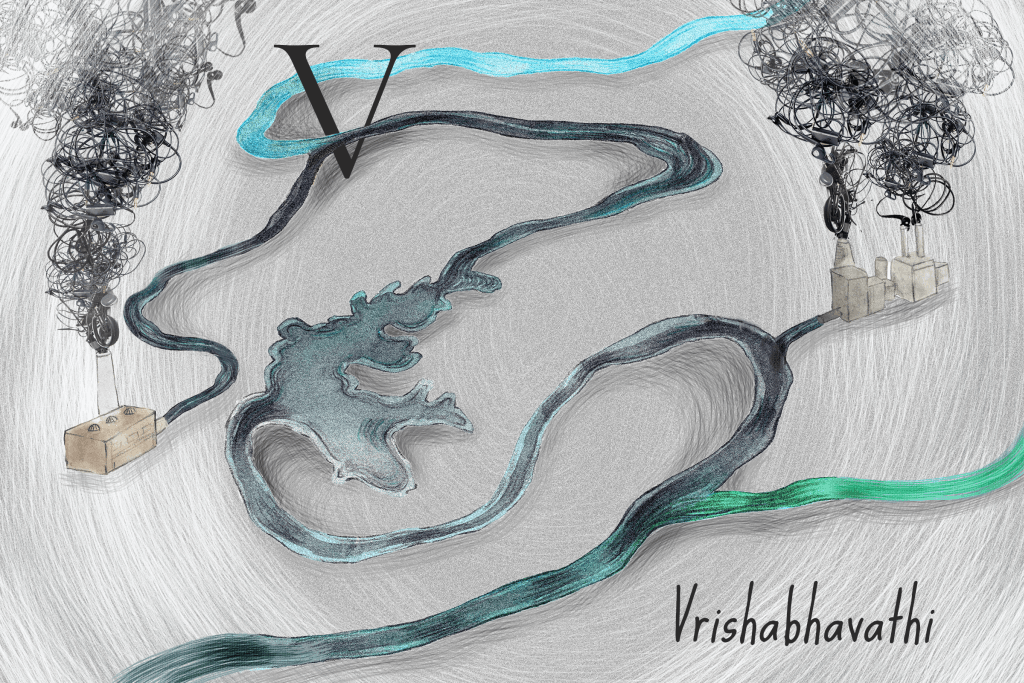

Vrishabhavathi

Vrishabhavathi is a river that flows through the south of Bengaluru, past 96 of the 198 wards of the municipal corporation. A 17th century Nandi statue at a temple in the Basavanagudi area of Bengaluru, has mentions of the river originating from the feet of the statue. The once-pristine river used as a drinking water source is now deteriorating and heavily polluted. Currently, lakes drain into this river, and untreated sewage let into lakes ultimately flows into the river too. Vrishabhavathi eventually winds out in the Arkavathi river, carrying the trash of the city and damaging water supplies downstream.

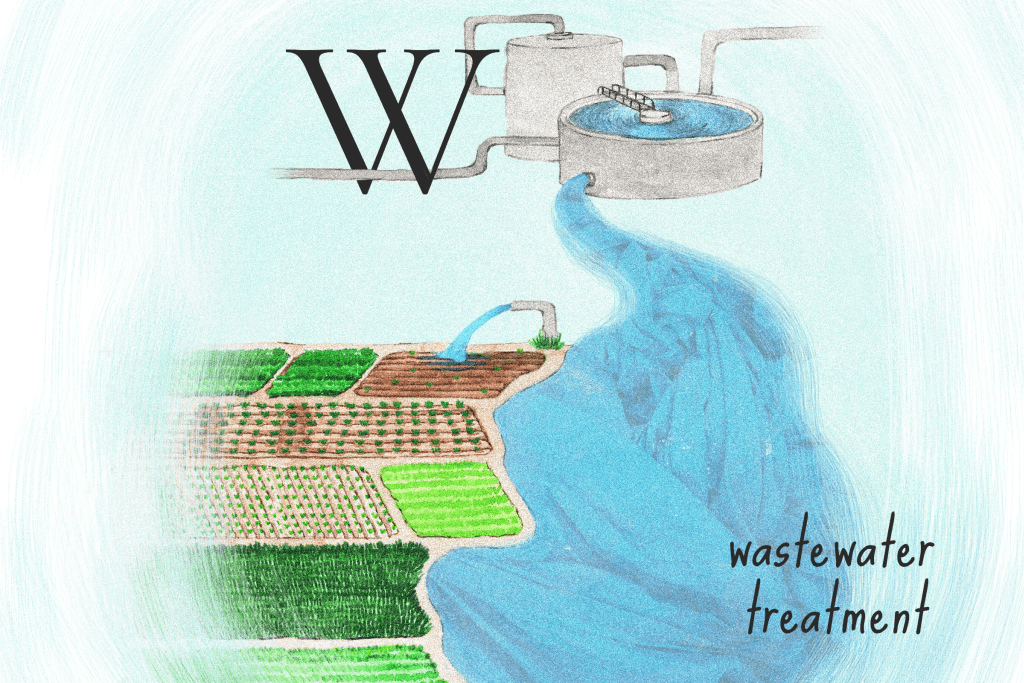

Wastewater treatment

What’s the new drought mitigation strategy to help Bengaluru survive tougher summers? Wastewater Treatment. Treated wastewater from sewage treatment plants are being pumped into city lakes. Currently, treated waste water is let into Doddakere, Sihineerkere and Bettakote lakes. An initiative of the Minor Irrigation Department, this pumping of treated wastewater will ensure that the lakes don’t go dry. The department monitors the water level in the lakes. Farmers are also very happy about this initiative as it has led to the increase in yield of borewells after decades.

Wastewater is also purified by natural wetlands, which are widely found in Bengaluru. Wetlands are known as the “earth’s kidneys” for the role they play in filtering pollutants from the water that flows in them.

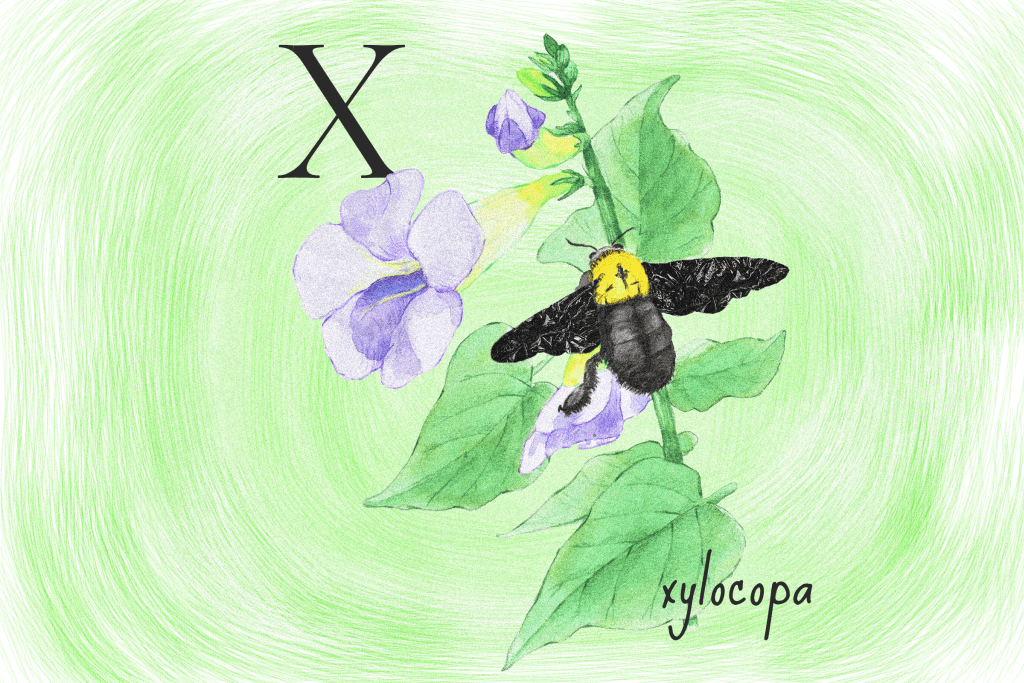

Xylocopa

Xylocopa is a carpenter bee genus with many species native to Asia. Widely found in Bengaluru’s lakes, these solitary bees hibernate during winters and emerge around spring time. Carpenter bees, as their name suggests, carve holes into wood or bamboo with their powerful mandibles. Xylocopa’s wings are iridescent due to light refracting through nanostructures in their wings.

The carpenter bees and other species of bees are essential for lake ecosystems because they help in pollination. Bee-eaters and other birds consume these bees. The bees thus support the entire food chain with their presence.

(Y)Eri

Eri (pronounced as yeri in Kannada) is a bund or structure covering a waterbody. It is usually a low embankment that controls the runoff of water and helps in water storage. Bunds can be naturally made up of soil, or artificially with rocks and cement. In Karnataka there have been incidents of lake bund breach in the past, which have resulted in inundation of many areas. Eri maintenance, therefore, is vital. In Bengaluru, many bunds were constructed while planning the city, way back in the 16th century, and are both historically and ecologically important.

Zooplankton

Zooplankton is a group of microorganisms that are important because they are the source of food for aquatic creatures in the lakes and other waterbodies. They are the bio-indicators of a healthy lake because they maintain biodiversity and act as a link between primary producers and higher trophic levels.

Concept and Editorial: Kartik Chandramouli

Illustration: Labonie Roy

Text: Priyanka Shankar, Aditi Tandon, Kartik Chandramouli

Review and Verification: Team Mongabay India, Team Citizen Matters, Manasi Pingle (Bengaluru Sustainability Forum), Shubha Ramachandran (BIOME Environmental Solutions), Ashwin Viswanathan (NCF)

This article is a part of a series on ‘Bengaluru’s Ecosystems and Biodiversity’, a joint project between Citizen Matters and Mongabay-India, supported by the Bengaluru Sustainability Forum (BSF).

Excellent,educative presentation of the lake system of Bengaluru

Very well compiled and illustrative article on the lakes on Bengaluru.

We live near BENIGANAHALLI Lake and would like to know how we can come together to make it a better Lake as we have seen deterioration in the upkeep of the lake after a lot of money was spent on its restorations a couple of years back.

What a lovely informative and beautiful article!