If you could time travel to the 1800s, how would Bengaluru’s lakes and water channels look? This passage from the ‘Deccan Traverses’ by Dilip da Cunha and Anuradha Mathur gives us an idea.

‘The sugarcane and rice crops looked most flourishing in the low wet land under the great tanks, which have all the appearance of natural lakes. Many of these have been most skilfully constructed, giving proof that the natives knew something of engineering, long before English rule and public works were thought of.’

The passage, referring to Bellandur Bund, is from a letter written in 1868 by Mrs L Bowring, the wife of the then Chief Commissioner of Mysore. The city of Bengaluru has often been referred to as Kalyananagara, or City of Lakes, owing to the numerous lakes that once existed. The British described the city as a ‘land of thousand lakes’.

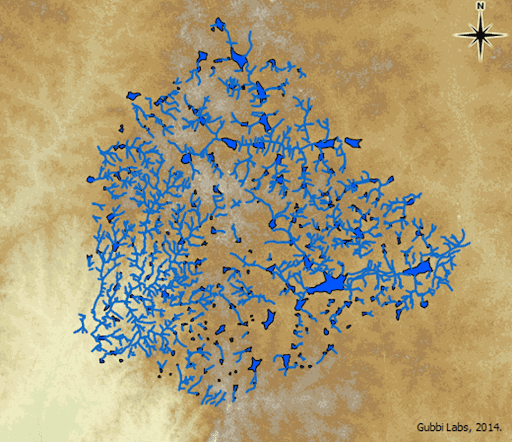

Bengaluru’s lakes or keres, as referred to in Kannada, are human-made tanks, built to serve as irrigation tanks, over centuries. Located at an altitude of 920 metres above mean sea level (MSL), Bengaluru does not have a river source, though it sits on two river basins, the Cauvery and the Dakshina Pinakini. These tanks were interlined through a cascading system with kaluves (canals) and rajakaluves( larger canals) connecting them.

Janaki Nair in her book ‘The Promise of the Metropolis: Bangalore’s Twentieth Century’ notes the role of tanks in the city’s development: “For a site that was not close to water source and was situated on an elevated ridge, a reliable supply of water for agricultural or domestic purposes was imperative… The provision of water through a system of tanks became a crucial element of a city building throughout the twentieth century.”

Smriti Srinivas in the ‘Landscapes of Urban Memory: The Sacred and the Civic in India’s High Tech City’, observes how the kere, along with the kote (fort) and pete (market), was central to Bengaluru’s spatial order from the mid-16th century till around 1800.

Esha Shah, author of the book ‘Social Designs: Tank Irrigation Technology and Agrarian Transformation in Karnataka, South India’, makes an important observation, “although tanks are spatially dispersed they actually are hydrologically linked’ – a “hierarchical system of flood control and water use” as Dilip da Cunha and Anuradha Mathur note.

Read more: Floods in Bengaluru: Engineered, legally!

The 2018 Environmental Management and Policy Research Institute report describes the three parts of drain-fed tank system: a) Catchment area through which the rainfall flows along the ground into the tank b) Tank bed, where water is arrested and stored, and c) Command area, where the overflowing water from the tank irrigates the crop. The other structures include sluice gate/valve, also called toobu, which is used to let water out of the lake into the canal system and waste weir or kodi, which is part of the bund, acting as a safety tool to let off excess water from the kere or lake.

Different kinds of water bodies in Bengaluru

Within the lake system, there are numerous, smaller water bodies, and other watersheds that were part of the wetland ecosystem. The Karnataka Lake Conservation and Development Authority Act, 2014 (KLDCA) states: “A Lake is defined as an inland water-body irrespective of whether it contains water or not, in revenue records mentioned as Sarkari Kere, Kharab Kere, Kunte, Katte or by any other name. It includes the peripheral catchment areas (Raja Kaluve) main feeder inlet and other inlets, bunds, weirs, sluices, draft channels, outlets and the main channels of drainages to and fro”.

The document also defines catchment area or watershed as an adjacent area draining into a single water body, consisting of streams, wetland, underlying groundwater, artificial channels, and stormwater drains.

What’s in a name?

Francis Buchanan-Hamilton, the Scottish physician-turned traveller, geographer and botanist, defined katte as a small reservoir supplying water for cattle to drink; kere as a large reservoir used for watering lands; and kunte as a tank formed by digging a square cavity into the ground.

In her book ‘Nature in the City’, Harini Nagendra explains the categorisation of water bodies by the Hoysalas: samudra (large water bodies); kere or eri (medium water bodies) and katte or kuttai (small sized pools of water used for washing clothes or for cattle). Smriti Srinivas, in the book ‘Landscapes of Urban Memory’, adds among other water bodies kola, a natural pond for the provision of drinking water, bhavi or a well and a kalyani or an artificial reservoir near a temple.”

The word sandra, means samudra, or sea and so places suffixed with ‘sandra’, had some reference to a lake or tank nearby. Localities with names ending with kere or gere were once lakes, some of them man-made, some’ natural’. Other common names include Hiriyakere, Heggere, Piriyakere for big tanks, Chikkakere for small tanks, and Kannegere for a new tank.

Bengaluru‘s stormwater drain network was designed for its topology

“Given the (design of) interlinked waterway systems, stormwater drains (SWDs) are important lifelines and they (now) play a very important role in preventing floods, ensuring groundwater recharge”, says Ram Prasad, co-founder, Friends of Lakes.

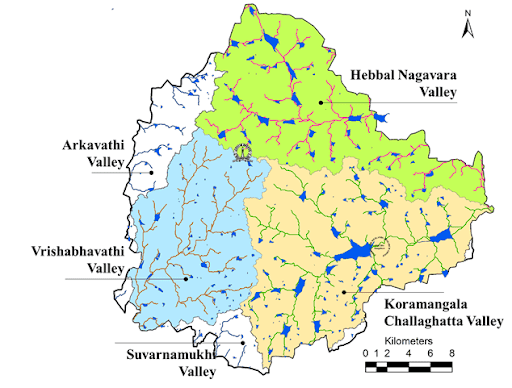

Bengaluru has four watersheds as precipitation flows, along the Koramangala – Challaghatta Valley (K & C Valley), Hebbal Valley, and Nagondanahalli Village (Ward 84- Hagadur, Bangalore East). In the eastern part, rainwater runoff flows into the Ponnaiyar river sub-basin through Bellandur and Varthur tanks (which are part of the Koramangala and Challaghatta valley) and Hebbal valley. In the western part, the runoff flows into the Cauvery river sub-basin through its two tributaries – the Vrishabhavati and Arkavathi rivers.

In addition, there are lesser-known five minor valleys – Marathahalli to the east, Arkavathy and Kethamaranahalli to the northwest and Kathriguppe and Tavarekere to the south. These lie outside the tributary area of the major valleys – Hebbal, Challaghatta, Koramangala, and Vrishabhavati, and they drain independently.

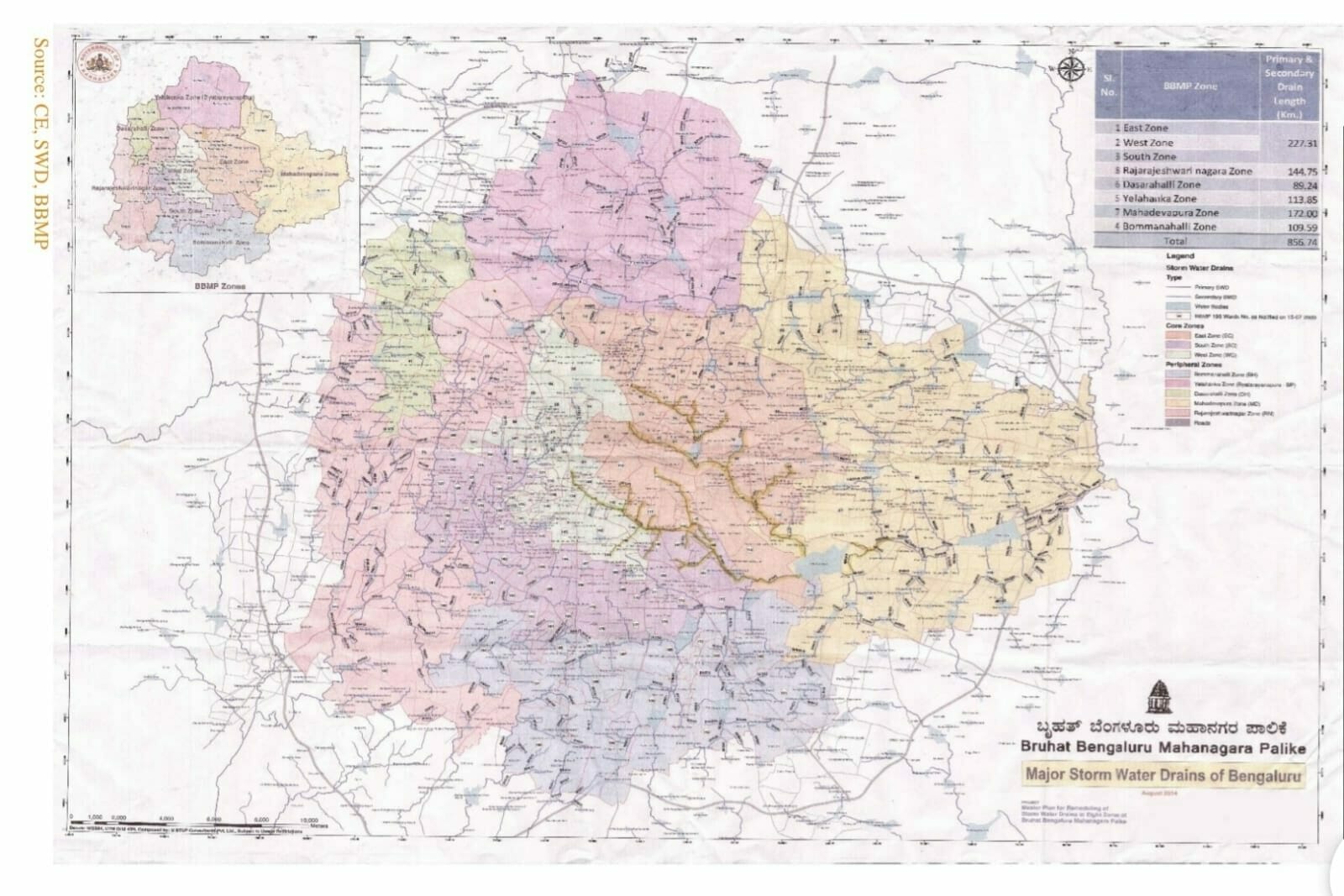

The nine valleys together form a unique and natural drainage system and both excess rain water and sewage flow down the city. The total length of storm water drains is about 840 kms. In the core areas, the length is 240 kms and outer areas it is 600 kms. The city has an average of 60 rainy days and receives over 900 mm of rain.

So what happened to the landscape of the city then?

As Harini Nagendra explains, the landscape in and around the city changed drastically over the centuries, even millennia. Harini says, “Fertile valleys in the gentle slopes of the maidan, where small streams could be dammed, and natural trenches deepened to store rainwater in lakes, became preferred locations for the establishment of settlements”.

As Bengaluru developed and industrialised in the late 19th century and the early part of the 20th century, its growing population as well as a number of private and public sector industries needed a reliable water supply. Hesaraghatta tank was first used to serve the drinking water needs of Bengaluru city, and piped water supply started in 1896.

The biggest impact was brought by the provision of piped water supply that removed the dependency on local water sources. Ram Prasad says, “Bangalore’s cascading drain system, a self-sustaining model, was disrupted in 1890 when piped water supply came to be (the norm).” In addition, there has been a lot said and written about the real estate lobbies and the pressure for land that led to the destruction of the tank systems.

Read more: Why Bengaluru is not immune to floods: It’s all about land (and money)

Disappearing water bodies and its impacts

A 2018 inventory of water bodies in 590 villages of Bengaluru Metropolitan Area (BMA) report by EMPRI revealed that there were 1521 water bodies in 512 villages, and the remaining 78 villages had no water bodies. The report highlighted the 684 water bodies existing in Bengaluru Metropolitan region, comprising 395 lakes (above three acres), 85 gokatte (between one and three acres) and 204 kunte (below one acre). It pointed out that about 837 water bodies have lost their characteristics and are no longer in existence.

T.V. Ramachandra, Coordinator, Energy and Wetland Research Group and Convenor at the Environmental Information system, Indian Institute of Science (IISc), in his 2017 paper Frequent Floods in Bangalore: Causes and Remedial Measure, points out, “Frequent flooding (since 2000, even during normal rainfall) in Bangalore is a consequence of the increase in impervious area with the high-density urban development in the catchment and loss of wetlands and vegetation.”

Current state of Bengaluru’s drains

There has been renewed focus on storm water drains, every time it floods, and recent years have seen a higher budgetary allocation on storm water drains. The BBMP Budget allocated Rs 51.7 lakh for the development of SWDs, especially in outer areas; Rs 186.7 crore for development works under CM’s Nava Nagarothana Yojane; Rs 50.8 crores for annual maintenance of SWDs; and Rs 50 lakh for desilting of drains. Yet little has changed on the ground.

The Performance Audit of Management of Stormwater in Bengaluru Urban area by the Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG), released in 2021, notes that the city ‘is a victim of a paradoxical situation – urban flooding on one hand and depletion of ground water table levels, on the other’. The report also points out the mismanagement of drains and the BBMP’s failure in protecting and maintaining drain infrastructure in the city.

It is time to redefine storm water drains as critical natural resources worthy of conservation.

The author would acknowledge inputs from Amanda Gann, Hita Unnikrishnan, Simmy Ganeriwala, Meera Iyer, Malini Ranganathan, Rohini Malur, Beula Anthony Vidya Prakash and Meera K.

[This article is part of a series ‘As the drain goes’, a joint project by Pinky Chandran, Nalini Shekar, and Citizen Matters, and is supported by the Bengaluru Sustainability Forum (BSF)]