At 8 AM Sunday, on February 6*, 2022, about 150 people congregated at the Khajaguda Cave Trail in Hyderabad. Among them were young scientists, engineers, IT professionals and artists. There were young couples, grandparents and children. There were adventure sport enthusiasts and bird watchers. Most of them had never met each other except through social media. Very few considered themselves activists.

Yet, this was no casual social occasion. They were agitated. They had a hunch that they were witnessing something horrifying: a mound of dirt the size of two football grounds and some twenty feet high, that had been created over less than six weeks. Under this mound, they knew there were several Indian screw trees and night-flowering jasmines which attract butterflies. Buried under this mound were rocks and caves that bear the marks of two and half billion years of evolution, have been challenging generations of rock climbers, and in some way, catapulting them into national and international adventure sport arenas.

Known alternatively as Baba Fakhruddin Gutta and Khajaguda caves, this hill was a quiet home to a dargah, a shepherd’s temple and a spiritual centre for Meher Baba devotees. It was discovered by the Society to Save Rocks in 2004 and became the daily haunt for the growing climbing and trekking community in 2011. In the last ten years, this hillock — carrying the signature marks of many hillocks in the Deccan Hyderabad region — has been engulfed and devoured by rapid development, and stands in the middle of high end real estate. It is now barely a 15 minute-drive from the Financial District of Hyderabad, which is home to multinational giants like Amazon and Microsoft.

Read more: Does nature stand a chance in this urbanisation frenzy?

The Khajaguda Hill, in the Manikonda Jagir Municipality — a satellite municipality of Hyderabad — is home to over thirty unique species of trees, about thirty species of aquatic and non-aquatic birds, and more than twenty species of butterflies. The terrain of these hills directs the movement of water towards surrounding agricultural land. Migrant workers often visit the hills in their free time, as do temple worshippers from Puppalaguda village (in whose revenue limits the hill falls), worshippers at the dargah, and Meher Baba devotees on Saturdays. Over the last ten years, at least ten thousand people have visited the hill for recreational trekking.

What’s happening at Khajaguda

After February 6th and over the following three weeks, the group that gathered that morning pulled together resources to amplify their reach through social media, and after a sustained campaign supported by several people, managed to draw the attention of K T Ramarao, Minister of Municipal Administration and Urban Development. The latter, in turn, directed Arvind Kumar, Chief Secretary of Urban Development, to inquire into the claims and demands of the campaign. Several days after the protest, the local police station registered a FIR against unnamed wrongdoers for encroaching into a heritage area.

As days turned to weeks and weeks to months, it became clear that the responsibility for this crime will never be fixed. The Mandal Revenue Officer and the Forest Department have both claimed lack of jurisdiction over the area.

Eventually it became clear that the Hyderabad Road Development Corporation (HRDCL), was the only agency holding the keys to the mystery. Authorised by the Hyderabad Metropolitan Development Authority (HMDA), HRDCL was furthering the construction of a 100 feet road that would inevitably cut through a large section of the rock formations.

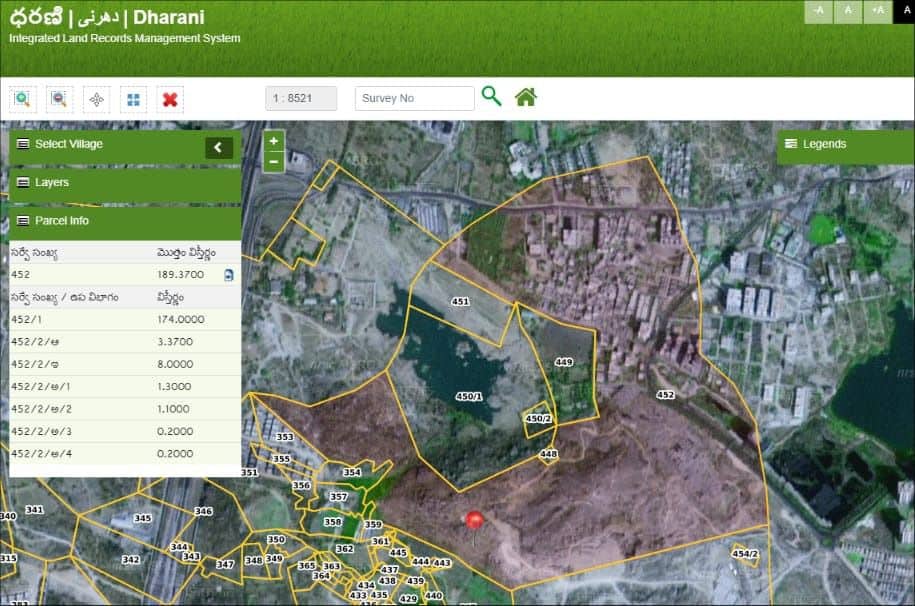

The construction of this road was sanctioned by the HMDA in July 2021. The road was to pass through several survey areas, one of them 452/1, which constitutes a part of the Khajaguda Hills. This sanction was in clear violation of a July 2019 High Court order that had directed the HMDA to take all measures to ensure that the rocks at Khajaguda (survey area 452/1, but also at 448, 450/1 and 450/2) were not “disturbed, damaged or destroyed.”

Disappearing boundaries

How did the HMDA violate a court order?

How did it mark a protected area for the 100 feet road?

At the heart of this crime is a process that environmental activists across the country’s big metropolises are now aware of. Anant Maringanti, Hyderabad Urban Lab calls it the “unmapping and remapping of urban commons”.

As land hunger grows, agricultural land in the urban periphery gets converted into real estate. But agricultural land never exists in isolation. It is embedded in ecological commons. These commons, which serve a variety of balancing functions, are gradually rendered as “wastelands”, their boundaries erased and encroached on. Maps disappear. Survey stones on the ground disappear. This wilful erasure of crucial land related knowledge in the form of documents, measurements records and maps leads to absurd situations.

Take the case of survey area 452/1. It came under the ownership of the erstwhile Hyderabad Urban Development Authority (HUDA), the predecessor of HMDA in 2004. In 2006, the HUDA issued a public notice with the intent to notify 452/1 (along with 448, 450/1 and 450/2) as a heritage precinct, which was eventually done through a government order, in 2009. This means that these survey areas had to be protected and preserved against any activity that would damage them.

But in 2011, the HMDA, through its 2031 Master Plan, marked 452/1 for road development. And when in 2019, the question of safeguarding these rocks at Khajaguda was brought before the High Court, the HMDA stated that it had issued a letter to the Collector of the area in 2013, directing demarcation and fencing of the survey areas for their protection.

In July 2019, the High Court directed HMDA to take measures to protect these rocks; two years later, in July 2021 the HMDA sanctioned the 100 feet road that would cut through them. And as this has happened the HMDA has been unable to ascertain where the boundaries of 452/1 lie.

This is not the first time a government body in Hyderabad has been negligent in marking boundaries of an area it was meant to protect. The story of encroachment of water bodies in Hyderabad is replete with similar omissions. The Necklace Road at Hussain Sagar, with its boulevards and restaurants, stands at the Full Tank Level (FTL) of the lake, the highest level at which water can be stored before it flows out of a surplus weir. When flash floods occurred in Hyderabad in October 2020, water in Hussain Sagar expanded, and finding no buffer or channel, inundated everything around the lake.

Across the city, the story has been the same: no government agency has released any data on FTLs or undertaken any exercise to fix the FTLs and by extension, boundaries of water bodies in the city. It is only when the government has to create property in a lake bed or foreshore that such an exercise is conducted. Through this deliberate act of not marking boundaries and revealing them only when required, a government agency often creates prime real estate in sensitive areas.

Blurring rural-urban boundaries

In the case of Khajaguda Hills, the location is important too. The HMDA was able to spend almost a decade deciding the fate of 452/1 without knowing its boundaries because the hills are situated in what is currently a satellite township: the Manikonda Jagir Municipality.

The area that currently constitutes the Greater Hyderabad Municipal Corporation (GHMC) has been shaped over many years, by absorbing villages around Hyderabad that were first declared satellite towns, which were then absorbed into the GHMC. Manikonda Jagir is one such recent satellite town, and like others before it, is in a transitional phase: agricultural activity still takes place and infrastructure is not fully developed.

Read more: How the upcoming Satellite Town Ring Road will affect lives and livelihoods around Bengaluru

Ownership of agrarian land in these places is often not private. Because land is embedded with the village commons, it becomes possible for different parties to encroach upon it, because such encroachment usually goes uncontested. In the case of 452/1, this encroachment would have taken place in the form of the 100 feet road meant to connect the patches of high-end real estate around Manikonda Jagir.

Will citizens save Khajaguda?

But now groups holding different stakes to the hills and the area around it have emerged. For the villagers residing close to the area, the possibility of the road brings with it the question of what they stand to gain from it. Will there be new business, will they be a part of the new development?

Rock climbers who frequent the hills almost every day have pressed upon the government to take custodianship of the hills. A campaign to protect Khajaguda has been pressuring the HMDA to pay heed to the illegal dumping of dirt and debris, demarcate the boundaries of the survey areas notified as heritage precincts, and ensure that the impending construction of the 100 feet road does not encroach into the rock formations.

Read more: Pune: Road widening stirs debate on how citizen groups can be more effective

In recent years, similar movements to protect urban commons — resources like water bodies, pastures, forests not meant for private use, held and shared in common by citizens — against harm caused by private interests and negligence in governance have grown in our cities. Protests against the Ennore Port in Chennai and the Mumbai Coastal Expressway, for example, have focused on protecting vital ecosystems that support numerous livelihoods.

The campaign to protect Khajaguda Hills, while important, cannot be the last one Hyderabad witnesses, because these hills are not the only vital commons in the city. Water bodies and wetlands that regulate the movement of water in the city have shrunk and disappeared at an alarming rate, increasing the possibility of floods during heavy rainfall.

The campaign to protect the Khajaguda Hills is also helping Hyderabad’s residents connect with and learn about the rich geology and ecology of the city, and can become the first step in acknowledging the necessity of these commons in our city. This is where new hope in building a civil society around shared resources and a resilient city lies.

*Corrigendum: The date had been mistakenly mentioned as February 5th in the first published version of the article and has been corrected. We apologise for the error.