The novel coronavirus scare globally has eclipsed many other issues, but water scarcity and how it adds to the challenge of the COVID-19 fight is one that cannot be ignored at any cost. Easy and regular access to clean water and proper sanitation is one of the fundamental requirements to keep the disease at bay, but in many urban areas of India, lack of such access may also emerge as one of the biggest hurdles for people trying to stay safe and healthy.

And it is not just the metropolitan areas or the bigger cities that suffer from insufficient water supply and flawed water management, but also smaller hill towns in the Hindu Kush-Himalayan (HKH) belt of the north, as a recent study has clearly shown.

A first study of its kind, conducted by a group of researchers from four countries during 2016-19 has been published by the journal Water Policy, highlighting the effects of haphazard urban planning, poor governance, water management and climate change on the water resources in 13 towns across India, Nepal, Pakistan and Bangladesh. The study was done under the project Himalayan Adaptation, Water and Resilience Research (HI-AWARE).

In India, the study was conducted in the towns of eastern and western Himalayas, namely Singtam, Kalimpong, Darjeeling, Devprayag and Mussoorie.

Water scarcity, urbanization and climate change

Most of these Indian towns were developed during the British colonial period as tourist destinations. In the course of time, as several national institutions and industries were established here, they began to attract migrants from rural areas. Population grew, exerting pressure on limited resources.

All these towns depend on springs that are fed by numerous local aquifers – which are natural underground water systems and form the primary means of water supply. The springs also contribute significantly to base flows in the Himalayan rivers. Monsoon rain replenishes the groundwater systems in the towns.

However, with increase in concrete surfaces in these urban centres, the water infiltration rate during the rainy season decreased considerably. This led to high surface overflow during monsoon, marked by overflowing of river banks and urban drains during heavy downpours but insufficient recharge of the underground aquifer system. While catchment degradation was identified as the main cause for drying up of springs in the last century, climate change is now emerging as a new threat in the 21st century.

The water stress in urban Himalayas is due to a combination of many factors. Management of the springshed, distribution lines and infrastructure are some of them. Climate change has emerged as a force multiplier as it further puts stress on the system.

Climate change is also responsible for changing the water regime of the river basins through its impact on glaciers and rainfall patterns. This change in the water regime affects the availability of water in the urban areas of the HKH region. It is manifested in reduced discharge in the rivers, springs and overexploitation of groundwater resources, and aggravates water demand. The crisis worsens during the dry seasons, particularly in cities that are popular tourist destinations where consumption levels soar during travel seasons, while recharge is limited.

Inefficient water management and distribution have caused further problems and deepened the rich poor divide in urban centres. Most of these towns receive piped water through the municipal distribution network, but a huge gap in demand and supply exists. Water supplied from these piped sources is found to be insufficient, irregular with high chances of contamination from industrial and domestic effluents.

Depleting sources

As local water sources have shrunk over the years, urban authorities have been compelled to augment supply by developing planned water supply systems from other distant sources, such as rivers, surface water bodies, etc. The physical topography of these Himalayan towns also restricts water supply from other sources.

As per a Niti Aayog Report on ‘Rejuvenation of Springs in the Indian Himalayan Region,’ natural springs provide 90% of drinking water supply in the hilly regions of Uttarakhand. Unfortunately these too, have been drying up due to rapid environmental degradation.

In the hill town of Mussoorie, two biggest sources of natural water, Jinsy and Bhilaru springs, have witnessed a reduction of almost 20% in their discharge. From 450 litres per minute in 2008 it went down to 365 litres per minute in 2017. Consequently, water tankers have become the most favoured source of water supply in the town. Similarly in Devprayag, another town in Uttarakhand, the natural springs have witnessed a decrease of more than 50% in discharge at the source in the past three years.

In another eastern Indian town of Kalimpong in West Bengal, springs are drying up, resulting in inadequate water supply. The town is a major tourist hub due to which several homestays, hotels, lodges have flourished in the last few years. These commercial units require almost 10,000 to 12,000 litres of water daily to run successfully, which is not possible with a regular connection. As a result, the business of water tankers have boomed in Kalimpong, making right to water contingent upon purchasing power. The hotel owner who is able to pay more gets a water tanker more easily.

Kalimpong town is a major tourist hub where several homestays, hotels and lodges have come up in the last few years. These commercial units require almost 10,000 to 12,000 litres of water daily.

Adaptation and coping: Rich versus poor

Many households now rely on deep boring from groundwater to meet their increasing demand for water. How well one copes or adapts again depends on the economic capacity of the household, with the more affluent households adapting better to water scarcity than the urban poor.

With dwindling water supply, most residents in these towns now depend increasingly on water tankers, bottled water and other private sources. Once again, this is more pronounced during the season when tourist footfall is high, with big hotels and businesses buying more water to meet increasing tourist demand. As a result, access to water is getting increasingly expensive.

Rich households can afford expensive bottled water or water from private tankers; while many have deep boring facilities and better storage facilities installed within their premises. This clearly depicts the divide between the rich and poor, and how climate change-induced water scarcity has differential impacts on these classes.

In towns like Singtam and Kalimpong, it was found that rich households and hotels and businesses had more than one municipal connection. Here again, was a case where the rich paid their way to access more water than their fair share.

The potability of water in these cities is also poor, because of year-round contamination. The inability of old water supply distribution systems to be scaled up to meet the current needs, is also responsible for poor water management and distribution. Pipelines and storage tanks are not repaired frequently enough, and often, feeder and supply pipes are rusted, twisted and too weak to hold sufficient water.

A modern metering system, which can ensure optimum water use efficiency and accountability and also preclude illegal tapping at different points, is missing. Hence, there is an overall lack of regulation of water consumption. Further the town also lacks adequate water harvesting systems.

The gender divide

In all of this, women are impacted more across all classes. Women spend a good part of their productive hours trying to collect water, especially in peri-urban areas. During periods of uncertain or diminished water supply, they spend most of their days (and nights) queuing up to collect water, which could otherwise have been spent on other productive work.

When we look at the representation of women in water distribution and management, their representation is nominal and marginalized, despite them being at the forefront of managing water for their household.

The way ahead

The study also analyzed various other adaptation mechanisms that have been put in place and can be adopted across other Himalayan towns and cities. The spring revival program “Dhara Vikas Yojana” of Sikkim has been notable in recharging the ground water sources and aquifers. Similarly, programmes to increase rainwater harvesting at household and community levels will help meet their needs during the dry season.

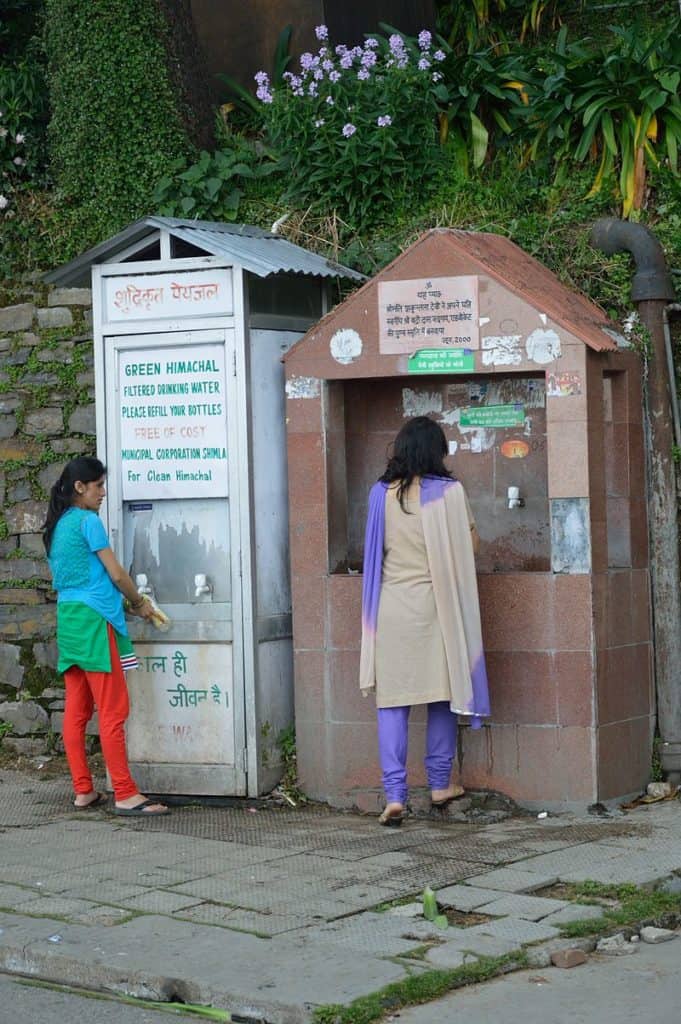

Many households have also started short term adaptation strategies for water efficiency and water conservation methods. In some Indian cities such as Shimla, progressive steps towards improvement and augmentation of the existing water supply schemes have been adopted. These include provision and rejuvenation of water supply lines, pumping machinery, leak detection machine, sluice valves, four water tankers and water meters (AMR), 25 water ATMs in 25 wards of the city and filtration plants at natural springs to improve the water quality, while rejuvenating the existing natural springs.

Various policy initiatives are also in place such as the National Mission for Sustaining the Himalayan Ecosystem in India and Housing Policy of 2011 to support long term adaptation. The National Action Plan for Climate Change (NAPCC) of India is also focused on sustainable urban development in mountain regions.

Good governance in water distribution and management is another issue that needs to be managed; currently lacking in most towns due to corruption and multi-level conflicts.

While planning new water distribution and management plans, it is crucial that climate change projections and impacts be taken into account. In the absence of such consideration and necessary mitigation measures, the new plans will not be sustainable and may fail miserably as water availability at source is declining at an alarming rate.

While I agree to assessment that authors present in the article. I feel Shimla’s case needs to be looked more critically and not glorified. Shimla is in process of initiating a full cost recovery for water. During my 2 month long fieldwork, most people complained about a hike in water bills. They have also set up a corporatised governance mechanism which continues to stay ambiguous when questions of accountability are raised.

It’s also important to remember that despite having a larger installed capacity (than the water demand) they have passed an extremely expensive augmentation project that brings water from Sutlej. This in no way is sustainable.

I do agree that Shimla has had some great initiatives to fix their current water supply system. They have fixed a lot of old infrastructure and that is commendable. I just feel the case needs to be looked more critically.