The first ten days of November 2017 has seen a furious and unprecedented level of dialogue and mainstream-media conversation around the topic of air quality, specifically in and about the city of New Delhi. While the situation in the national capital is indeed dire, a large part of that conversation has been aided by citizens, journalists and community activism groups having access to scientifically validated real-time, hourly-updated data of the air quality levels in their neighborhoods and surrounding areas.

The conversation around air quality levels for several years primarily involved scientists and researchers from leading Indian institutes and a few committed non-profits and policy research groups. The introduction of scientifically validated real-time data has suddenly enabled ordinary citizens to start tracking and monitoring their levels on a daily basis and to start questioning their elected representatives on the steps they are taking to mitigate the problems.

Tweets from editors and concerned citizens showing real-time air quality data from government approved monitoring stations started to gain wide reach and traction:

And now monitors at three #AirPollution toppers (ITO, Anand Vihar, Ghaziabad) are conking off? @rsutaria @UrbanSciencesIn @airqualityindia @soniandtv #MyRightToBreathe Overall Delhi tonight may break last year's record of 497 #DelhiSmog pic.twitter.com/HnXqy1DIe4

— Chetan Bhattacharji (@CBhattacharji) November 8, 2017

Public health experts also were tracking real-time data of air pollution levels and started sharing their perspectives on the issue:

Yet another reminder that whether it be stubble burning, brick kilns, thermal power plants or industrial emissions, the impact is widespread. Nothing shows that more clearly than the extremely high AQI figures in the indo-gangetic plain right now. pic.twitter.com/WOYYII0nRP

— Bhargav Krishna (@bhargavkrishna) November 8, 2017

And citizens from everyday walk of life started reporting real-time data too:

Stay indoors everyone. https://t.co/eRaCKhc580 pic.twitter.com/rKa9Ix2ij8

— Nikhil Pahwa (@nixxin) November 11, 2017

Automated technology solutions like #breathe allowed people to access real-time data by just sending a tweet:

Air quality levels as recorded over the past 1 hour. #breathe pic.twitter.com/HkZha6KaIt

— Chasing Methane (@IndiaSpendAir) November 12, 2017

Why this matters

The access to such data has allowed a more focused and credible dialogue to happen around the critical and time-sensitive issue of air pollution. The alerts and health advisories related to air quality need to be issued in a timely context (on a daily or weekly basis) and not a few months before or after. The access to real-time data in the hands of citizens mean that elected representatives and policy-makers who have access to budgets and the responsibility to implement effective policies can be questioned more regularly and not only during election time. This is a good thing.

One of the reasons for the level of focus and dialogue happening in the national capital right now is also because of the very high number of air quality monitoring stations that are reporting real-time data from different locations there.

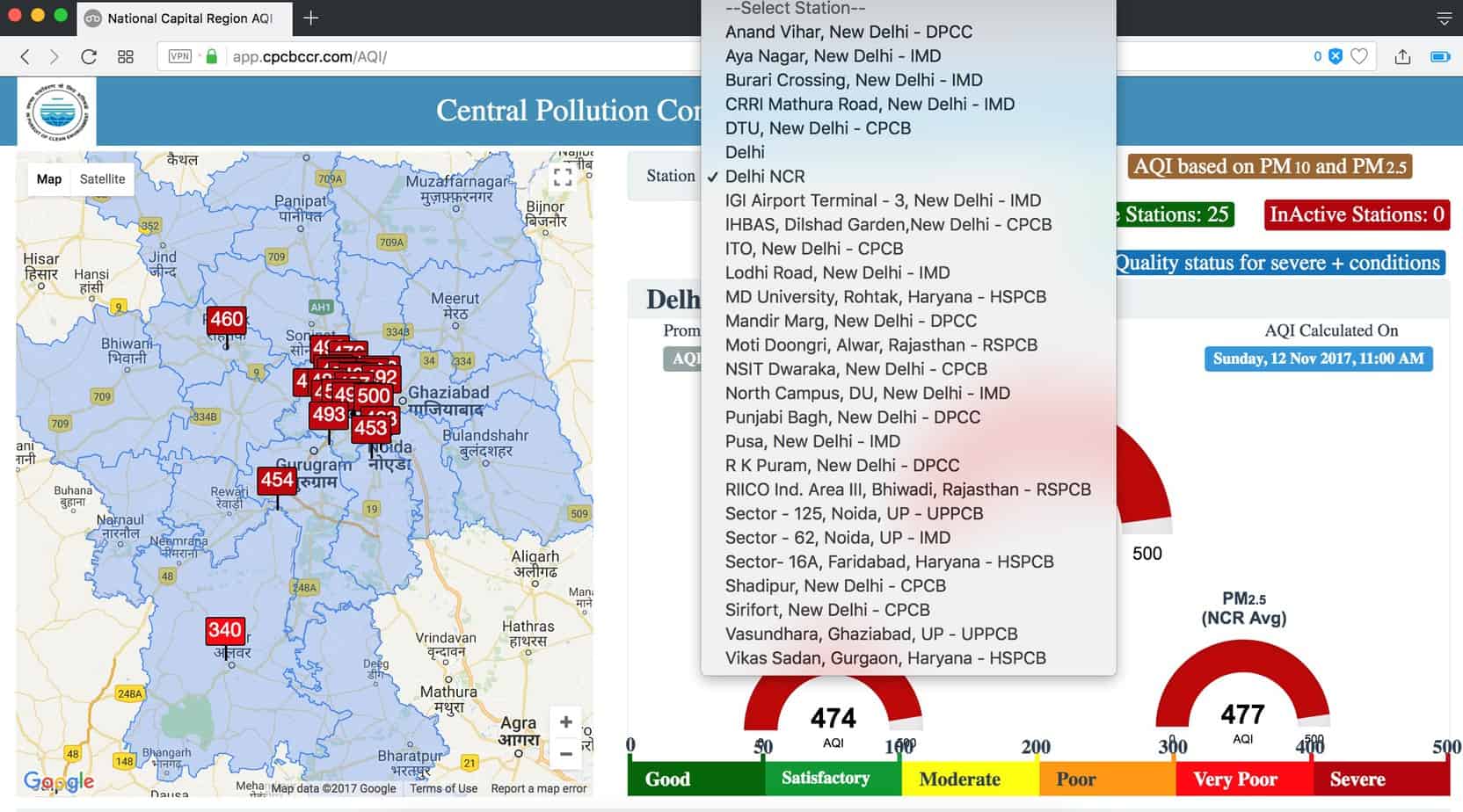

A recently launched “National Capital Region AQI Dashboard” for the Delhi NCR area, home to an estimated 46 million people, showed data from about 25 real-time monitoring stations for the region from different government agencies – including DPCC (Delhi Pollution Control Committee), CPCB (Central Pollution Control Board), IMD (Indian Meteorological Department), UPPCB (Uttar Pradesh Pollution Control Board), HSPCB (Haryana State Pollution Control Board), RSPCB (Rajasthan State Pollution Control Board). As of September 2017, the CPCB itself had around 86 Continuous Ambient Air Quality Monitors (CAAQM).

Are we doing enough?

However, for a country that has five mega cities (urban agglomerations having population of over 10 million people), 50 urban cities having a population of over 1 million people and about 475 cities and towns having a population of over 100,000 people, the number of government run realtime/continuous ambient air quality monitors are woefully inadequate.

New Delhi has a disproportionate number of real-time air quality monitoring stations, as reported in The Wire. Being the national capital region, having the highest population in the country and the maximum resources (financial, technical/scientific and administrative), administrators in New Delhi have a responsibility and are in a position to set the direction that can be followed by the rest of the country.

The neighbouring state of Uttar Pradesh, having a population of over 200 million people has the next highest number of continuous air pollution monitoring stations across the state, a meagre 10!

Singrauli, a town of over 1.2 million people and a designated Critically Polluted Area (CPA) in Madhya Pradesh has no real-time government monitoring stations. This is symptomatic of the pollution monitoring situation in the country.

Independent scientifically validated low-cost and real-time air quality monitoring stations can assist in tracking air quality levels in towns and cities where there are no government monitoring stations available.

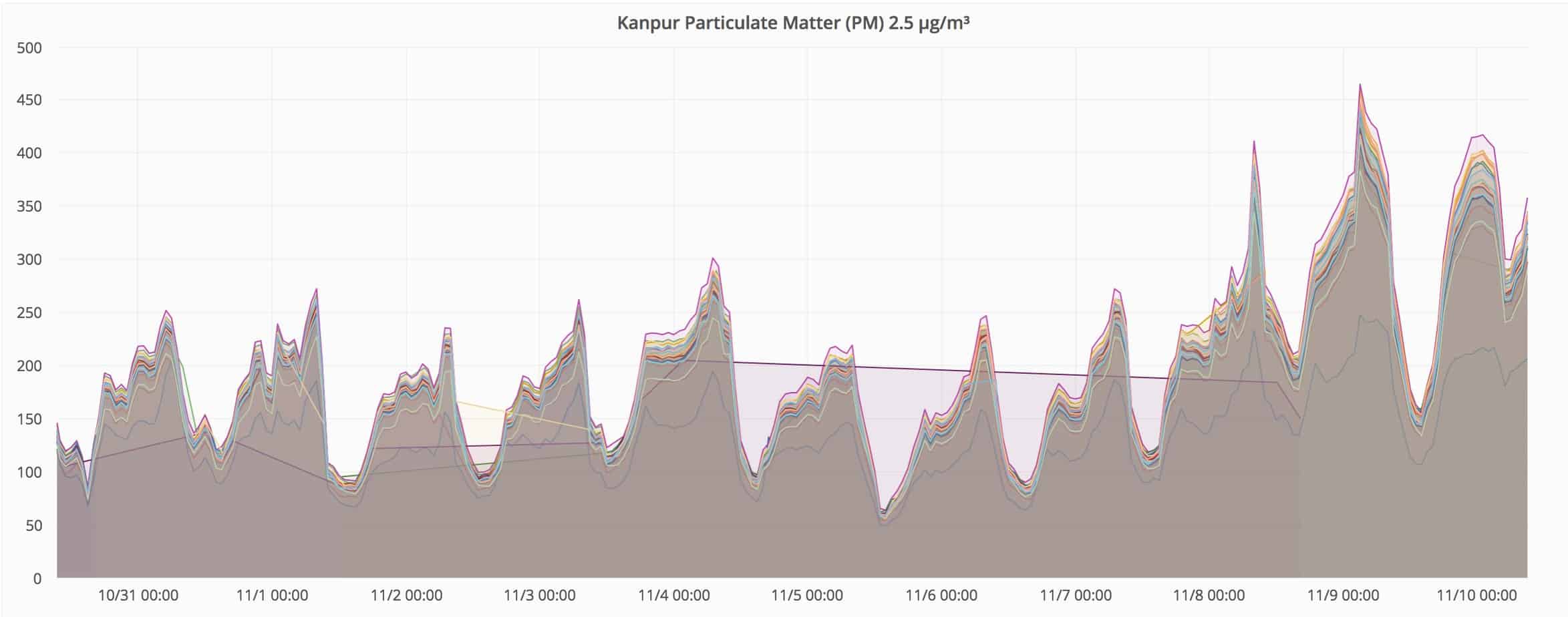

An analysis of real-time air quality data for a period of 10 days – from Nov 1 to Nov 10 – in the city of Kanpur has found some useful diurnal air quality related trends. It was found that the air quality levels there were worse from the hours of 6am to 7am and were the cleanest from the hours of 2 to 3pm.

Similar diurnal trends in air quality have been observed in the cities of New Delhi with a significant difference between the peak levels and the lowest PM2.5 levels during the day.

Insights based on such hourly real-time data can make a direct policy level impact. School timings, especially timings for outdoor/playground activities can be adjusted based on real-time PM2.5 levels.

The Haryana Education Minister released a directive on November 8 to officially change the school timings to 9am to 3.30pm. Steps such as these are examples of a responsive government policy framework. More such policy directives should be encouraged, which are brought about by citizen voices and backed by sound scientific data and information.

Promptness and participation: The key to solutions

The US EPA along with the California-based SCAQMD (South Coast Air Quality Monitoring District) has an advanced programme for performance evaluation of “low-cost” air quality sensors. They have established the “AQ-SPEC” (Air Quality Sensor Performance Evaluation Center) which has evaluated and validated a large number of “low-cost” particulate matter (PM2.5) sensors against Federal Equivalent Method (FEM) grade equipment. The results available on their site clearly indicate that the “low-cost” sensors have highly correlated data with reference grade equipment.

In India, the Department of Science & Technology (DST) in collaboration with Intel have launched a Research Initiative for “Real-time River Water & Air Quality Monitoring”, administered by the Indo-US Science & Technology Forum (IUSSTF). Initiatives such as the one launched by DST-Intel have the right balance of encouraging low-cost monitoring initiatives along with the rigour of building a scientifically-validated and calibrated network.

The building of scientifically validated real-time low-cost air quality monitoring networks in India has been underway for the past few years. An important and critical step in this is for policy-makers to be able to make their policies become responsive to real-time conditions that are affecting the citizens.

The city of New Delhi has developed and launched the “Graded Response Action Plan (GRAP)” in January 2017. The plan received formal approval from the Environmental Pollution Control Authority (EPCA) only in October 2017. Even after having a responsive policy in the city, the implementation was found to be severely lacking. An analysis by IndiaSpend has found that the state government should have released over 30 alerts for air quality levels which it never did.

While the government agencies are slow to respond, it is incumbent upon citizens to become aware of the environmental pollution conditions in their own neighbourhood. Awareness is half the problem solved. Once citizens become aware and start asking the right questions, solutions will start to emerge. There is not going to be one single panacea for the air quality problem that is afflicting Indian cities. It is going to require hundreds or thousands of smaller citizen initiatives to make a difference. The time to start on that is today.

Air pollutant touched calamitous levels in Delhi. The municipal authority ordered sprinkling of water on the roads to get the dust settled and it also banned cutting of trees. Hoping foe the best.