“Bade mushkil se Eid mana paye,” says Mohammad Irshad, 53, of Shehjenabad locality in Bhopal’s old city area. “Pani hi nahin ghar mein. Mehmanon ki kya khatirdari kar paatey (we observed Eid with great difficulty. There is no water in the home. How could we entertain guests)?

Bhopal, the “city of lakes”, is reeling under an unprecedented water shortage over the past 20 odd days, with the old city area, housing 43 per cent of the capital’s 21 lakh population, hit particularly hard. The entire supply of 30 MGD (million gallons per day) to these mainly low-income residents is from the city’s iconic Bada Talab or Big Lake. What they are currently getting is 20 MGD, which too may be cut off as water levels in the lake reach its lowest point ever.

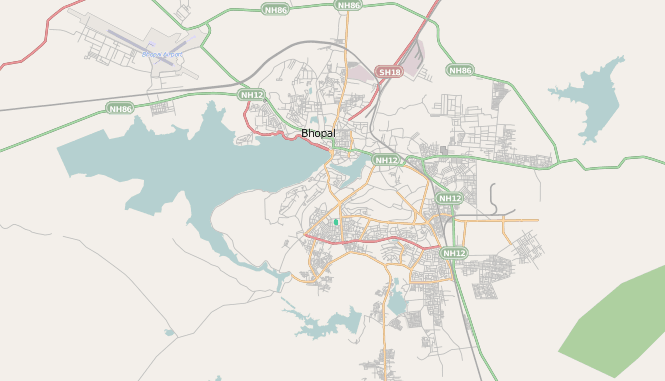

The Upper Lake, or Bada Talab as is it is popularly known, was constructed over a thousand years ago by Raja Bhojdev mainly for irrigation in the region and spanned 250 square miles, according to A L Basham, the author of the “Wonder that was India”. Renamed Bhojtal some time back, it is a single lake on the western side of the city with a surface area of 36 square kilometres and catchment area of 361 square kilometre. Along with the smaller lake or Chota Talab located towards the city centre, the two water bodies constitute the Bhoj Wetland area which is mostly rural, with some urbanized areas around its eastern end. This is a Ramsar site or a wetland area of international importance.

Map created from OpenStreetMap project data,

“Water-pumping from the Upper Lake, which is currently supplying water in the old city’s densely populated areas every alternate day, can continue only for the next 17- 20 days,” said M L Pawar, Assistant Engineer, Zone-II, Bhopal Municipal Corporation (BMC) on June 16.

Given that 90 per cent of Bhopal’s water needs of 72 MGD is met from surface water reserves and 10 per cent from ground water reserves, the importance of ensuring the preservation of the Upper Lake is evident. Yet, such has been the deterioration of the lake that BMC officials now say that the water level has dipped to 1651.80 feet, which is below the minimum level of 1652 feet (the lake’s full tank level is 1666.18 ft) needed to keep the lake alive.

All recreational activity on the lake has been stopped. According to the municipality, the water in Upper Lake would last till June end. To handle the situation, the civic body proposed to minimise supply of water from the lake and make up the shortfall with water from Kolar and Narmada. Thankfully, the arrival of monsoon has offered some respite for the residents of Bhopal and also for the civic body which has been able to maintain its limited water supply because of the rains. “We can maintain water supply for another two weeks,” said M L Pawar. “The demand for water has gone down somewhat over the last few days. But around 300mm of rainfall is needed to make a visible impact on the water level of Upper Lake.”

“We are facing a water crisis,” admitted Bhopal Mayor Alok Sharma. “The rain gods have not been kind to us.” Sharma has asked for Rs 100 crore from the state government to deal with the crisis. He, however, maintained that the municipal corporation is monitoring the situation and “we will ensure supply of water through tankers in affected areas.”

Ineffective lake preservation projects

While authorities talk of short term measures to tide over the crisis, there seems little hope of being able to revive the lake in the near future, despite hundreds of crores being allocated to maintain and improve it over the past 20 plus years.

The first lake preservation project, named the Bhoj Wetland Project, was begun in 1995 financed by a Rs 240-crore loan from Japan and generous grants from the Centre. The objectives were to promote improvement of overall environmental conditions of the Bhoj Wetland and water quality of the Upper and Lower Lakes by implementing several pollution control and environmental conservation measures in the two lakes and their catchment areas.

The project included diverting the sewers from the two lakes, and for their de-weeding and de-silting. But little happened on the ground, and over the years, Bhopal’s Upper Lake continued to shrink in size due to encroachments, while about 35 open sewer nullas from various colonies around the lake continue to empty into its waters.

“In several phases during the implementation of the Bhoj Wetland Project, officials and experts compromised on priorities,” said Abdul Jabbar, a social worker and activist championing the need to conserve the Big Lake. “Money that was meant to be spent for the conservation of Bhopal’s lakes, diverting the sewers away from the Upper Lake and encroachment on the nullahs, was spent on fixing floating fountains, building pathways etc. They are systematically damaging the healthy eco-system of the lake.”

A few years later came Project Uday, this time with a loan of Rs 179 crore from the Asian Development Bank, to ensure clean drinking water supply in Bhopal and to address the problems of inadequate urban infrastructure and degradation of the environment in four cities, namely Bhopal, Gwalior, Indore and Jabalpur.

Implemented by the state’s Department of Urban Development and Housing, its purpose was to provide basic services of water supply, sanitation, garbage collection and disposal in these cities. Indirectly, it sought to promote sustainable economic growth. Some of the main project objectives were urban water supply and environmental improvement; public participation and awareness programme, including the enhancement of community-based inputs for environmental management, capacity building, and training for livelihoods and project implementation assistance via support to the state project management unit (PMU) and city project implementation units (PIUs). Even a gender action plan was envisaged. Unfortunately, much of this too has remained on paper.

Surprisingly, overall, the lake’s water quality has not deteriorated too much. In 2017, a study of the water quality of Upper Lake conducted by Pawan Kumar Singh and Pradeep Shrivastava of the Department of Environmental Sciences and Limnology, Barkatullah University, Bhopal, showed that most water quality parameters were more or less within the permissible limits.

Vanishing green cover

Adding to Bhopal’s woes is the fact that the city has lost much of its green cover in the last couple of decades, compounding its water woes. According to a report released by the Global Earth Society for Environment Energy and Development: “Bhopal has been fast heading to be a city without trees…due to a massive decline in the forest area of Bhopal from 35 per cent to 9 per cent during 2009 to 2019.” If the trend continues, the city will be left with just 3% of its forest cover by 2025.

On June 10th, a meeting to draw up the City’s master plan was held where it was decided that a team of officials will study the master plan of Amravati, the newly built capital of Andhra Pradesh for the planning of Bhopal Capital Area. The meeting was attended, among others by Urban Development and Housing Minister Jaivardhan Singh and Science and Technology Minister P C Sharma. Ironically, Amravati itself has come under criticism from several environmentalists.

At the meeting, however, Rajya Sabha MP Digvijay Singh emphasised that while making the master plan, the catchment area of the Upper Lake should be planned in such a way that water flow to the lake is not interrupted. The meeting also decided that special care should be taken to enhance Bhopal’s green cover and that more trees should be planted than the number felled for development work. According to Minister Jaivardhan Singh, the Master Plan will be readied in a year.

Unfortunately, by then, the Upper Lake may well be dead and gone.