A study conducted by the Chennai-based NGO, Information and Resource Centre for the Deprived Urban Communities (IRCDUC), on World Bank-financed housing projects in Chennai and across Tamil Nadu reveals that nearly four decades after the implementation of the project, a majority of the beneficiaries still await land titles and sale deeds that were promised to them.

The study, titled ‘Implementation of the World Bank-financed Housing Projects in Tamil Nadu and its Impact on the Deprived Urban Communities’, has been compiled based on the existing information and updates available in various citizens’ reports and participatory assessments that were facilitated by IRCDUC along with technical support from the International Accountability Project (IAP).

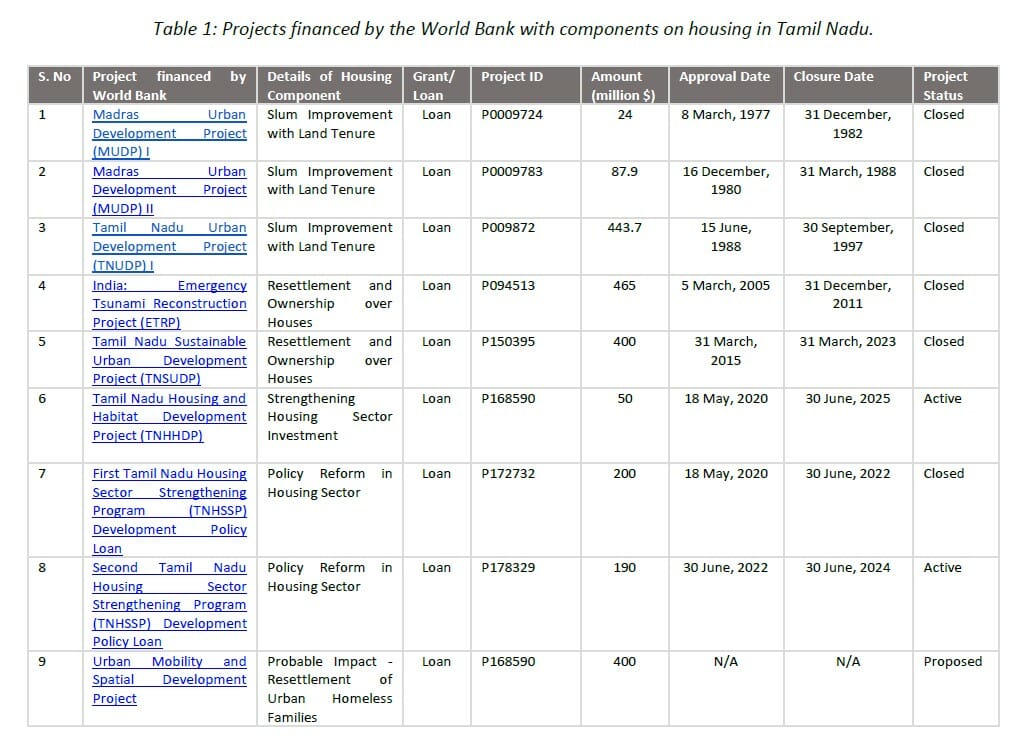

According to the study, the State government has been receiving grants and loans from the World Bank since June 1958. For more than four decades there have been several projects financed by the World Bank with housing components impacting the lives of the urban poor in Chennai and across Tamil Nadu.

However, decades on, the intended beneficiaries of the projects continue to live in fear of being evicted from their homes.

Read more: A wishlist to tackle homelessness in Chennai

Evolution of World Bank financed housing projects in Chennai

The Madras Urban Development Project (MUDP) I, which was initiated with World Bank funding commencing from 1977 to 1982, is considered to be the testing ground for urban reforms in Tamil Nadu. The second phase of the project was carried out from 1982 to 1987. These projects were implemented in two phases with an objective ‘to develop and promote low-cost solutions to Madras’ problems in the areas of housing, employment, water supply, sewage, and transportation, and in particular making investments responsive to the needs of the urban poor’.

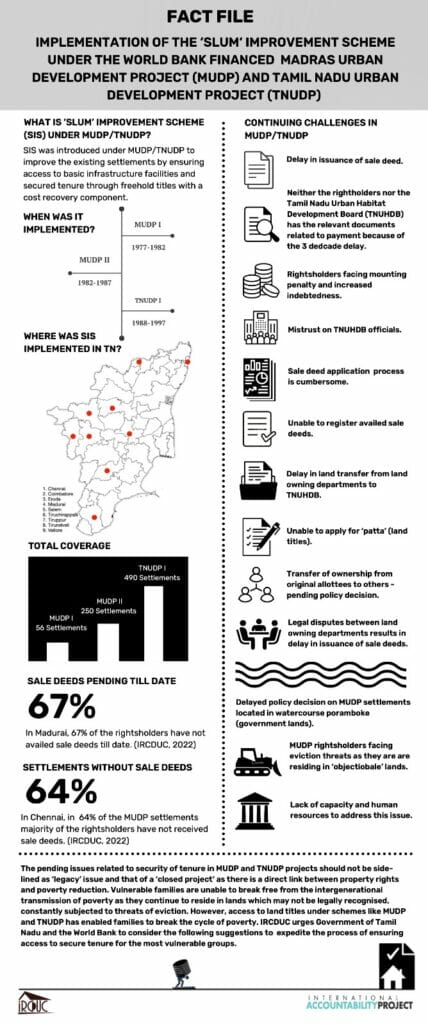

To curtail the programme of constructing ‘expensive tenements’ and to improve the existing settlements, the ‘Slum Improvement Scheme’ (SIS) of MUDP was introduced to provide access to basic infrastructure facilities and security of tenure through freehold titles with a cost recovery component.

The SIS component of MUDP focused on in-situ development and transfer of land rights. In Chennai, both MUDP I and II projects extended to 298 settlements (56 under MUDP I and 250 under MUDP II) benefiting 48,459 rightsholders.

MUDP II was followed by the implementation of the Tamil Nadu Urban Development Projects (TNUDP) in three phases.

Read more: Residents of Chennai’s resettlement sites fight against all odds to receive their pension

Change in approach to financing of housing projects

Under Tamil Nadu Urban Development Project I, the slum improvement scheme was expanded to 10 cities across Tamil Nadu and 490 settlements (84,000 families) were developed.

TNUDP brought in crucial changes to the approach of financing. On one hand, TNUDP I had initiated the concept of a financial intermediary and involved the private sector in the urban process, TNUDP II not only promoted private sector participation but also focused on institutional strengthening of facilitating the services beyond financing the projects. The reforms were driven to ensure a return on the investment along with visible changes within the institutional and policy framework.

The second phase of the TNUDP II brought in crucial changes that have continued to affect deprived urban communities since then.

Under the World Bank-financed TNUDP II, a pre-feasibility study on ‘Identification of Environmental Infrastructure Requirement in Slums in Chennai Metropolitan Area” was conducted for TNUHDB in 2005.

This study pointed out that providing housing at alternative locations is not only 10 times more costlier than upgrading the slums at the same location but also creates disturbance to the social and economic lives of the community. However, in the next few decades, resettlement housing programmes dominated the public housing programme for the urban deprived communities.

The lauded housing programme SIS, financed by the World Bank, that guaranteed land rights for communities soon faded away in the future projects. SIS was instrumental in shifting the focus from constructed tenements to developing individual plots with tenure rights, however after TNUDP I the focus yet again shifted back to the purpose-built tenement scheme.

Findings on World Bank financed housing projects in Chennai

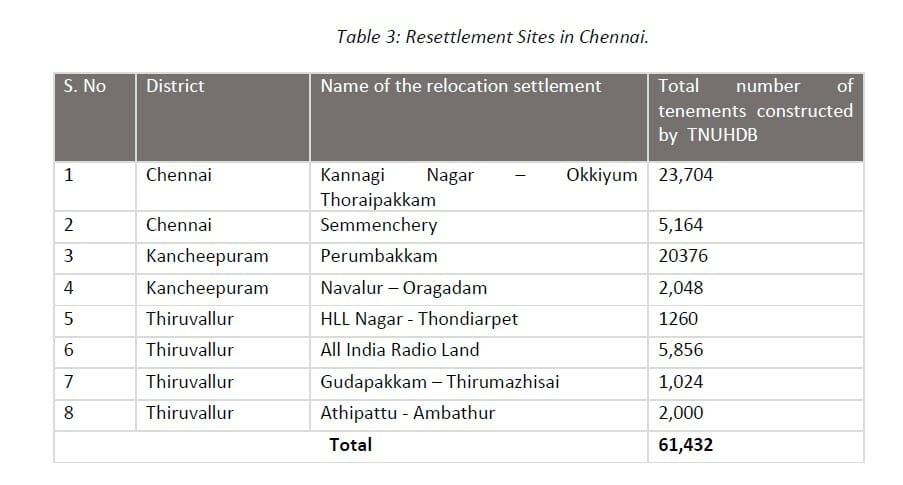

Chennai has around 8 resettlement sites (located on the fringes of the city) that have emerged over a period of 20 years (2000-2020). These resettlement sites in Chennai comprise 61,432 families where over 2.5 lakh displaced slum residents are currently residing.

After 35 years of implementing the MUDP and TNUDP schemes in Chennai, IRCDUC conducted an assessment in the months of August and September 2022 to understand the challenges faced by the rightsholders in accessing the security of land tenure that was promised to them.

Some of the findings of the assessment are mentioned below:

Delay in issuance of Sale Deeds: Of the 50 settlements assessed by IRCDUC in Chennai, sale deeds (which will ensure the security of land tenure) have not been provided to the families in 32 settlements. Even in the other 18 settlements, some families have received the sale deeds but not all.

Challenges in applying for Sale Deed: Because of the decades-long delay, some of the original allottees have passed away and the families find it difficult to identify a legal heir because of non-cooperation and dispute among family members. In cases where the original allottees are alive, the elderly parents are dependent on their children for finances and hence are unable to make the pending payments. It is further difficult for elderly widowed women to convince their children to make payments.

Non-availability of documents: Many families do not have the basic required documents over a period of time due to floods, fires, or pests. People also did not know that the absence of payment receipts amounts to non-payment. Therefore, many who claim to have paid the amount, do not have the receipts to prove their claims nor does the Board have any documents to verify peoples’ claims.

Mounting penalties: Various reasons including upward revision of prices midway through payment, lack of transparency, and limited access to the right information have deterred people from making the payments on time which has resulted in incurring penalty interest.

Because of the mounting penalty, people have expressed they are willing to pay the dues however in two to three instalments. However, it is revealed that people have dues from Rs. 8,000 to Rs. 54,000 and hence they are unable to make the payment in a single instalment as demanded by the TNUHDB. It is also to be noted that the penalty amount will increase even for the period between the instalments which has not been communicated to the rightsholders.

Mistrust of TNUHDB officials and cumbersome process in applying for sale deeds: In some cases, the payment details available with the communities and TNUHDB vary, resulting in mistrust. There are no transparent mechanisms for making people understand the calculation for pending payments. Officials claiming to be representing the Board have demanded bribes further increasing the mistrust.

Delays by landowning departments affecting beneficiaries

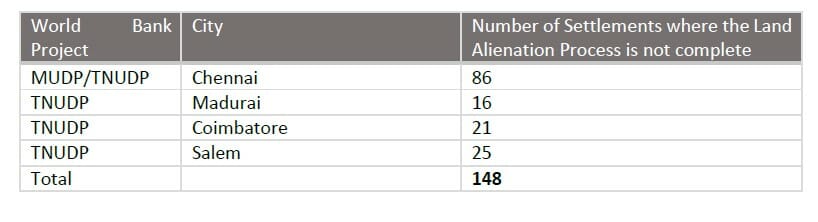

One of the problems for the delay in issuing sale deeds is the delay in the transfer of these lands by the landowning departments to the TNUHDB. The land, in many of these settlements, belonged to other departments like the Revenue and Disaster Management Department, the Urban Local Bodies, the Public Works Department etc. The TNUHDB in these cases has developed the settlements only based on ‘Enter upon Permission’ and has not completed the land alienation process.

A Government Order dated June 15, 2018, was issued in 2018 by the Housing and Urban Development Department for the formation of the Empowered Committee to address the land alienation issue. However, despite setting up an Empowered Committee there is a delay in the process of land alienation from the land-owning department to TNUHDB.

In Kandha Pillai Street of Perambur in Chennai, the rights holders of MUDP Phase II, have not accessed their land titles because of ongoing litigation between the Hindu Religious and Charitable Endowments Department (HR&CE) – the land-owning department and TNUHDB. The 51 families are asked to pay the rent to the HR & CE department in addition to the payment to the Board as the TNUHDB has ‘developed’ the settlement without completing the land alienation process.

In some cases, the original allottees have transferred the ownership to others and have moved out of these locations. For example, in Chennai’s M.S. Nagar of the 88 houses surveyed 12 families have moved to other locations after transferring the ownership to others. There is currently no policy decision about the regularisation of the plot for those who have transferred ownership to non-allottees.

This apart, there is no policy decision (available in the public domain) about the issuance of a sale deed for the settlements that are in the Watercourse Poramboke (government lands). There have been instances where these allotments have been cancelled in Chennai to evict the rightsholders of MUDP. However, the documents related to the decision are not available in the public domain.

In Chennai, out of the 50 settlements assessed by IRCDUC, 7 are in watercourse poramboke lands, with the allottees likely to be evicted and resettled.

The threat of eviction of rightsholders continues to exist because of the delay from the Government to address the issue at the earliest despite acknowledging the existence of this problem.

“The Government of Tamil Nadu was aware even in the 1990s that 60% of the settlements developed under MUDP/TNUDP are in ‘objectionable’ lands. Even though Government Orders were issued as early as the 1990s, there is no policy decision related to the MUDP/TNUDP settlements located in ‘objectionable lands’,” reads the IRCDUC study.

Recommendations by IRCDUC for the World Bank

- World Bank should have a clear position related to closed projects especially when there are continuing impacts on the rights holders. There needs to be specific strategies for addressing prolonged adverse impacts on communities in closed projects.

- The rights holders of the MUDP, especially the settlements located near waterways are currently facing eviction and resettlement because of delayed policy decisions from the state. The rightsholders of MUDP have invested their entire lifetime investment in the houses under the assumption that the house and the land were theirs because the project was ‘guaranteed’. Now they are in the threat of losing their land, housing, and their entire lifetime savings. World Bank needs to continue to monitor the impacts and ensure that the implementing agencies resolve the issues.

- Considering the unresolved issues and prolonged impacts of the projects on the rightsholders – such as non-access to tenure rights, mounting penalties, and increased debts – the World Bank must propose remedial measures through its ongoing Tamil Nadu Housing and Habitat Development Project.

- Need for evolving robust “Responsible Exit Principles” to address issues related to the long-term adverse impacts of projects on rights holders, non-adherence to agreed deliverables of the project and to evolve future courses of action to address gaps in implementation, especially when it is related to inordinate delay or prolonged adverse impact on rights holders. This also calls for evolving mechanisms to assess whether the proposed exit strategy is aligned with the agreed deliverables of the project, identify long-term impacts if any, and explore additional actions to address the gaps in the implementation. The performance audit reports should also have a specific section on exit strategies followed and the future course of action if there are gaps in the fulfilment of deliverables or in the case of pending adverse impacts on the rightsholders

The recent projects financed by the World Bank have reduced the role of the government to that of a ‘facilitator’. This will have a long-term impact on the deprived urban communities for whom, the government is the custodian of their basic rights.

It is high time for the government to take proactive steps to ensure that the rightsholders under MUDP and TNUDP are able to access their right to secured tenure.