Uyali* was among the 220 garment workers fired by Slam Clothing Private Limited in January 2020. Two months later, the textile manufacturer situated at Mahindra World City in the outskirts of Chennai shut down operations, citing ‘irrecoverable losses due to the COVID-triggered lockdown.’ More than half of the workers haven’t received their dues from the Provident Fund (PF) yet. Like hundreds of her colleagues, Uyali is still waiting. “My salary of two months remains unpaid to this day. I had to hunt for a job in the middle of a pandemic when I did not even have the money to afford my daily commute,” says Uyali, who managed to find a job at another garment factory.

In the shadow of COVID-19, hundreds of garment workers fell prey to wage theft and illegal layoffs. “30-40% of workers were laid-off, dismissed or refused jobs in the Chennai belt alone,” says Sujata Mody, president of the Garment and Fashion Workers Union (GAFWU).

But while the pandemic actually worsened the plight of these workers, leaving them in the lurch, injustice and exploitation of workers in the garment industry has been a historical, albeit rarely discussed, reality.

The garment industry in Chennai

Women hold a majority of the low-paying jobs in India’s multi-million-dollar garment industry, which employs at least 12 million workers overall. Hopes of a decent salary and respite from their poverty-stricken lives lure many women from the underprivileged sections to the industry, where they work as tailors, helpers, quality checkers and supervisors.

Ready-Made Garment (RMG) exports from India were to the tune of USD 1106.7 million in May 2021, showing a positive growth of 114.2% against the corresponding month of May 2020, according to a report from the Apparel Export Promotion Council (AEPC). The largest RMG manufacturing centres, spread across Bangalore (Karnataka), Tirupur and Chennai (Tamil Nadu) and the National Capital Region (NCR), have a combined workforce of well over a million women and men, according to another report.

In Tamil Nadu, Chennai is the second biggest epicentre of the garment industry, after Tirupur. Pockets of Chennai such as Ambattur Estate, SIPCOT, Poonamalle and Thiruporur comprise the hub of the industry, strewn with factories that manufacture global brands such as Zara, H&M, Polo etc.

There are more than 40 registered factories in and around the city, with a minimum of 300 (and a maximum of 2500 workers) in every factory. These factories get orders from global brands that take various parameters such as quality and price into consideration before placing work orders. “Only a few companies, however, check if these factories safeguard the rights of their workers,” says a supervisor from a garment industry in MEPZ Tambaram.

A never-ending cycle of exploitation

The real picture is depressing. Women workers are chronically underpaid. In gross violation of human rights, garment workers fight exhausting targets, low pay and sexual harassment on a day-to-day basis.

The garment industry has historically seen a dominant proportion of women employees, because as Sujata Mody, president of the Garment and Fashion Workers Union (GAFWU), puts it, “it is easy for male employers to extract work and throw their weight on women”.

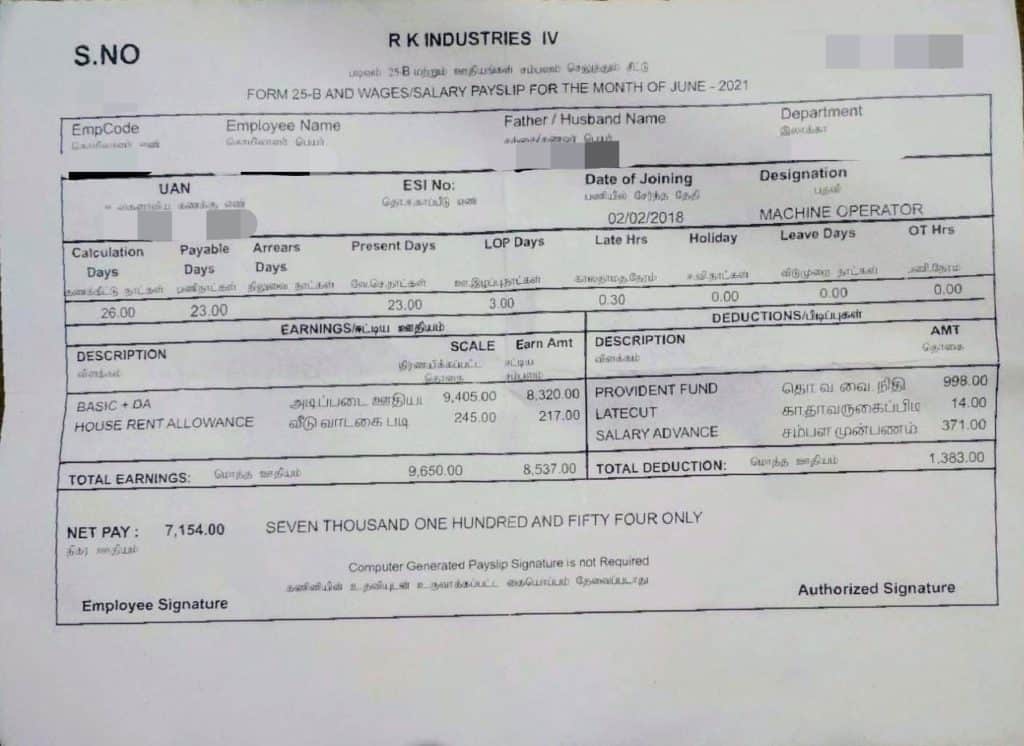

Women face injustice at every phase of their work-life in these factories. A majority of women are hired informally (on contract basis), violating several provisions of the Contract Labour (Regulation & Abolition) Act, 1970. “There is an absence of social security and other benefits for contract workers, even though they are eligible for Provident Fund and health benefits under law. In some cases the deductions for social security benefits are never made from the workers’ wages, while in others they may be made but not deposited in the accounts of the workers,” says a study conducted by the International Labour Organisation on the working conditions of migrant garment workers in India.

Some findings cited in ILO study

- The male-female wage gap in the garment sector is one of the highest in India at 34.6%

- Women and adolescent girls employed in the garment and textile industry have a higher chance of developing menstrual irregularities

- A survey of 200 workers in export oriented factories in the NCR found that only 44% were enrolled under the provident fund (PF) organisation and got account numbers for PF. Similarly, only 41.5% of the workers were enrolled at the ESI corporation and had ESI cards

Ironically, despite discrimination and violence, women from the marginalised sections of society continue to look for jobs in the sector. “My priority was to get a job to educate my children. If not in the garment industry, what choice did I, with no educational qualifications and skills, have?” questioned Srikala*, a garment worker.

Read more: Struggling to meet living expenses, garment workers demand wage arrears of Rs 1862 crore

Laws flouted

The Tamil Nadu Minimum Wages act, 2014 mandates every employer in the garment industry to pay not less than Rs 223.85 a day for all textile workers, regardless of whether the employment is contractual or permanent. This is exclusive of the compensation paid for food and transportation. However, only a fraction of employers adheres to the law.

Kumari* (40), who works as a tailor in a garment company at Thirukulakundram, takes home a meagre pay of Rs 5000 a month, despite having been working for six years. “What these workers get is way less than what the law says. Many companies pay their employees as per the minimum wages law, but do not pay them for working overtime. They even charge for the transportation provided. It is the duty of the labour department to monitor these leaks in the system,” says S Palaniammal, Organising Secretary of Pen Tholilalar Sangam (Women Workers Union).

According to the Gratuity Act 1972, (applicable to those working in factories for wages), permanent workers in the garment factories, who have completed 5 years of service in an organisation, are eligible to receive 15 days of pay a year. A worker earning Rs 300 per day should thus get an additional Rs 4,500 every year once she has completed five years of continuous service in the same organisation. This is usually paid cumulatively upon end of service (retirement, resignation, termination etc).

However, employers have many strategies to avoid paying gratuity. “My employer fired me just as I completed 4.7 years in the organisation. Two months later, he called me back and hired me again, but with no hike in the salary and no gratuity,” said Devi*, who works for a reputed textile company in Thiruporur.

“Forced resignations by the workers every four or five years is a common practice in garment factories, as it ensures workers have no continuity of employment. It makes their jobs precarious,” says Sujata Mody. Yet, given the lack of other employment opportunities, these workers continue to accept such terms of employment, despite the injustice they face.

According to the Tamil Nadu Labour Welfare Rules, 1973, every employer in the textiles/garment industry should be a member of the Tamil Nadu Labour Welfare Board and contribute a fixed sum per worker per year to the board, as does the employee and the government. According to the Rules, every employee contributes Rs 10 per year and every employer in respect of each employee, contributes Rs 20 per year to the Fund; the Government in respect of each such employee contributes Rs 10 per year to the Fund.

“Ideally, the labour board should use the money to provide financial compensation to the registered workers in times of need. This, however, remains on paper,” adds Palaniammal.

Why do garment workers live in silence?

For many women in the industry, wage disparities and the absence of benefits are so common and trivial that they accept it unquestioningly. Harassment at the workplace presents a real predicament, though.

As the day ends, Kumari comes home fighting back tears every other day. Kumari has to get a token to use the loo. Her supervisor yells at her if she takes more than two loo breaks during her shift and Kumari’s salary is deducted even if she takes a day of sick leave. “Every day, I have to shed my dignity, only for the money,” she says in a low tone.

Sexual harassment by male employers and seniors are not uncommon either. Pramila*, an employee at a prominent factory, was sexually harassed by her supervisor three years ago. “He made me work beyond the office hours. and turning off the lights, he touched me inappropriately,” says Pramila, fighting back her tears. More than that one incident itself, it is the overall bitter experience with the system that leaves her distraught.

Pramila has made two visits to the Kancheepuram collectorate, three visits to the Chengalpet collector’s office and countless visits to the welfare office at Kancheepuram and the Chengalpet police station, seeking justice. “I had to borrow money from acquaintances to make these visits. While I am still repaying my loans, my perpetrator just left the country and is happily working abroad today,” she says.

Read more: Survey: Garment factory workers say they won’t, and can’t, work longer hours

Who is responsible?

The heartrending narratives of these women raise an important question: Are there no complaint mechanisms or legal support systems in place that these workers may rely on? There are, in fact, strong legislative frameworks that safeguard the rights of garment workers in India but lack of enforcement and an anti-worker attitude in the labour department is what makes the situation how it is.

As per the Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal) Act 2013, factories must constitute an Internal Complaints Committee (ICC) with seven to eleven members. But through our conversations with about ten workers, we learnt that only one worker was aware of the existence of such a committee, while two admitted to having faced sexual harassment at work. Clearly, awareness is sorely lacking.

Even an employee in the Human Resources department of a prominent firm in the industry responded in the negative when asked if their firm has an ICC. “But there is a welfare officer, who addresses any complaints by workers,” he said.

“Most factories have poorly functioning ICCs or none at all. The only complaints these committees receive are about things like non-availability of drinking water (at the workplace). In a few cases when workers did complain about sexual harassment, they were the ones who ended up getting fired,” says Dhanalakshmi A, Vice President, GAFWU.

It is the responsibility of factory inspectors in the labour department to inspect the companies in their jurisdiction once in three months. “The district monitoring committee, comprised of the District Collector, Deputy Commissioner of Labour (DCL) and Assistant Commissioner of Labour (ACL), should inspect the factories to ensure smooth functioning of the ICC. But it seldom happens,” says S Palaniammal.

Despite repeated attempts, Secretary, Labour Welfare and Skill Development Department, R Kirlosh Kumar was not available to comment.

More voices needed

Taking on the multi-billion dollar companies and holding them accountable for the prevailing working conditions will require collaborative efforts by the labour department, union and workers. But while there are many representative bodies that fight for the rights of garment workers, statistically the participation of workers in the unions has been disappointing. “Only three or five out of 100 workers join the unions in the sector,” says Sujata Mody, adding that the employers actually discourage workers from joining the unions.

There is evidence, though, that a full-fledged union representation can turn the tables. When companies failed to pay the workers as per the TN Minimum Wages Act, 2014, GAFWU launched various campaigns. “We sent various representations to the labour department, which eventually ordered the companies to pay the arrears to the workers,” says Dhanalakshmi.

“We took part in letter campaigns, sent notices to companies and even protested multiple times. Only one textile company in the whole of Chennai paid the arrears to the workers. The impact could have been much bigger if more workers were part of the union,” she adds.

Why don’t workers join the unions then? “Because the management makes the lives of those in the union a living hell. My pay was drastically reduced and my work was harshly criticised after I joined the union. Unions are only for those who have the resilience and the means to put up a strong fight against the system,” says Srikala.

One thing that clearly emerges from all the conversations is that the persistent discrimination and violence against garment workers stems from the absence of effective monitoring by the labour department. Companies that breach and manipulate labour laws are never penalised so that they carry on with impunity. “Ideally, the labour department with its many departments should enforce the 44 labour laws (including the Minimum Wages Act and the Factories Act). But, the reality is different and painful,” says S Palaniammal.

(*Names of the workers have been changed to protect their identity)

Good report. It is painful to note they are not having organized unions to fight the injustice.Govt. should come forward to help them