Indore city has been declared the cleanest city in India for the 6th time in a row in the recently announced Swachh Survekshan 2022 results. Indore has consistently performed well in the Swachh Survekshan survey since 2017 due to its integrated approach to solid waste management and efficient waste processing. The city, with a population of nearly 2 million, generates about 1,900 tonnes of solid waste per day. The Indore Municipal Corporation has successfully integrated the collection, transportation, processing and disposal of solid waste generated in the city.

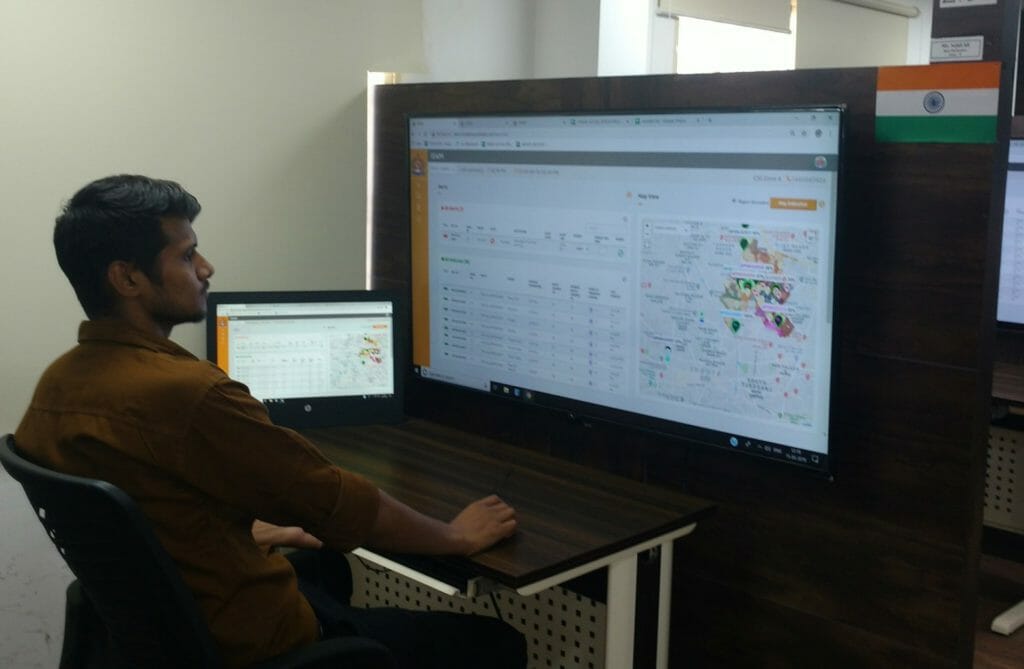

What made this feat possible is the rigorous waste management system Indore follows, where the segregated waste from households is tracked live to ensure the waste is collected in separate bins. The segregated waste is transported to the respective wet and dry waste processing facilities in separate containers. The wet waste is converted into organic compost and biogas, whereas the dry waste is further sorted, cleaned, baled and sent to recycling. This integrated system, supported by strong awareness and people participation, has helped Indore stay on top as the cleanest city in the country.

While a few cities like Surat and Navi Mumbai, which are second and third in the rankings, have set up a decent solid waste management system, other major cities are still lagging behind. Out of the 4,320 cities that participated in the Swachh Survekshan 2022, 48 cities have a population of more than a million, and 382 cities have a population of more than a lakh, the latter generating more than 85% of the 1.5 lakh tonnes of solid waste generated every day in Indian cities.

Read more: How RWAs in Gurugram are showing the way out of urban India’s waste crisis

The Swachh Survekshan 2022 toolkit allocated 40% weightage for processing solid waste, 30% for segregated waste collection, and 30% for sustainable sanitation initiatives. Solid waste processing is the most complex and difficult process in waste management. States like Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh have focused on this process since the Swachh Bharat Mission was launched, which has improved the rankings of their cities. On the contrary, states like Bihar, Karnataka and Tamil Nadu are at the bottom of the table of states with more than 100 ULBs, and have not shown much improvement despite having close to 90% waste collection.

Complexities in processing solid waste

Processing the solid waste generated in Indian cities is assumed to be a simple process, but it is not. The mixed nature of solid waste with varying moisture, quantity and character poses serious challenges to waste processing.

Additionally, the lack of techno-financial resources required to operate solid waste processing plants prevents effective solid waste processing.

The waste generated in Indian cities roughly consists of 60% biodegradable material, 25% non-biodegradable dry waste, and the remaining 15% consists of silt, soil, and other particles. The input to output ratio in waste processing could be 20% if the waste is well segregated. Based on experiences at various waste processing facilities, the same may be around 12% if mixed with dry waste. The remaining portion of the waste is lost as process and moisture loss.

About 5% of the non-biodegradable dry waste could be sold to recycling units, and the remaining 20% could be used as Refuse Derived Fuel. The 15% inert material consisting of silt and soil must be scientifically landfilled.

Municipal solid waste processing requires efficient systems for managing all types of solid waste. Although most Indian cities have set up waste processing facilities and have invested in civil works and electromechanical equipment, the waste processing itself is not carried out efficiently, resulting in unprocessed waste piling up in waste disposal sites, causing serious environmental and health challenges.

Read more: Are micro composting centres in Chennai doing their job?

The challenge for local corporations

ULBs are grappling with a lack of financial resources and technical know-how to implement efficient and sustainable solid waste processing facilities. Also, the business itself is not self-sustainable since most of the recyclables like hard plastics, metals etc. are picked up by formal and informal workers and only non-saleable dry and wet waste reaches landfill.

The process of converting wet waste to organic compost takes about 40 days and requires sieving machines, backhoe loaders, tipper trucks for turning, sieving, bagging etc. Typically, only about 20-25% of the operational expenditure could be recovered from the sale of compost.

The ULBs then have to incentivise the operational deficit of about 75% through tipping fee per tonne of the waste processed, which is a fee paid by the ULB to waste processing plant operators to meet the operational deficit. Many ULBs fail to accommodate this operational deficit, preventing the entry of private players.

A large section of stakeholders assumes that solid waste is just a matter of sieving the waste to recover organic compost. However, composting is a technical process that requires adequate temperature, air and moisture to ensure biodegradation and then sieving, value addition and marketing of organic fertiliser. ULBs fail to accept that the process which can be explained easily is indeed a complex scientific process.

Way forward for poorly performing states

States like Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh have been able to do better due to their sustained focus on waste processing. Prioritising solid waste processing creates a back-end requirement for a segregated waste collection and transportation system, transforming how solid waste is managed in the cities. States like Karnataka and Tamil Nadu should prioritise municipal solid waste processing by budgeting for the required funds, which are marginal compared to their financial ability.

All the ULBs with more than 1 lakh population should be mandated to process the daily waste generated and produce good quality organic compost. The smaller ULBs with lesser financial abilities could try collaborating with NGOs and self-help groups to manage solid waste, although the quantity of waste generated by these small towns is just around 10-15 tonnes per day compared to the 500 tonnes per day and above in cities with a population of more than a million.

Well framed about rural and urban waste process and challenges …