The Karnataka 2023-24 budget must be examined through the lens of the Congress party’s welfare and policy promises. They gave several assurances towards making ‘public works’ more accessible, particularly in Bengaluru. Towards this end, a section titled ‘Sector 4: Comprehensive Development of Bengaluru’ was added to the budget document. In this article, I analyse to what extent these developmental initiatives align with the needs of the urban poor.

I also highlight the missed opportunities and inadequate measures within the budget and how it fails to address the complexities of Bengaluru’s urban crisis.

Read more: Hundreds of crores of SWM budget lie unutilised, yet no sign of scientific landfills

Poor drainage systems

Point 327 of the budget states: To mitigate the ill effects of climate change and control floods in Bengaluru, a project with the assistance of World Bank at a cost of Rs. 3,000 crore will be implemented. Sluice gates will be installed in all the tanks to control the flood situation under this scheme. It will help in controlling the speed and quantity of flow of water.

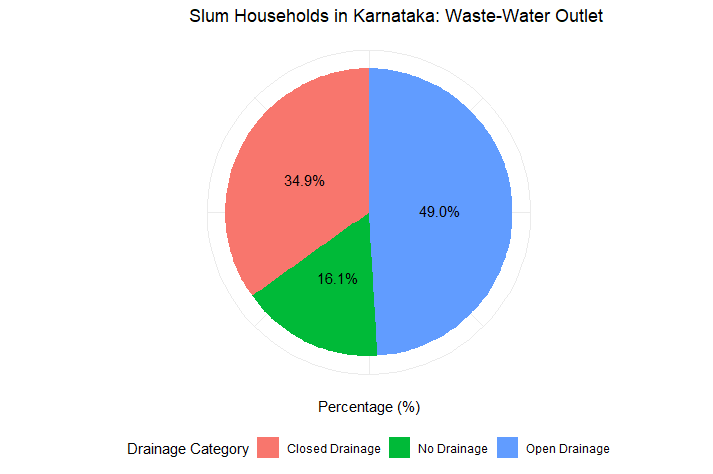

The misalignment between the goals of urban development and the well-being of the urban poor has affected municipal governance. Bengaluru’s urban development goals focus primarily on making it a global IT hub. However, basic infrastructure continues to be of poor quality. I show this paradox of governance by using municipal data on drainage (see Figure 1).

A proper drainage system is crucial not only to control urban flooding but also to attract global investments. Therefore, drainage across the city needs to be improved. The issue is amplified in urban slums where poor drainage systems cause health problems because people come into contact with dirty sewage and wastewater.

Although the World Bank-funded project is a welcome step, it fails to tackle the underlying issue, which is improving the capacity of the city’s drainage system.

Read more: Open letter to the BBMP Commissioner on BBMP’s expenditure and efforts in waste management

About 50% of drains in Karnataka slums (predominantly located in Bengaluru) are open drains, according to the Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation 2023 data. Drainage issues in slums have led to severe disruptions of everyday life during heavy rains. Open drains worsen the vulnerabilities of the urban poor. The situation should make us pause and reflect: How are the World-bank funded sluice gates going to solve urban flooding and related concerns while we face the grave issue of open drains? The budget does not address this municipal concern and overlooks the daily challenges of a significant population of the city.

The issue of waste production

Point 333 of the Budget says: Thrust will be given to process the waste locally by mandating the producers of the large quantity of waste, including commercial complexes, hospitals, and hotels to process the waste at their level itself.

While the budget acknowledges waste production as a significant policy concern, it does not allocate any resources to address this. It is unclear how waste will be processed locally. It does not capture the scale of waste production in the city. The new government has not taken any steps to integrate the local community into decision-making processes.

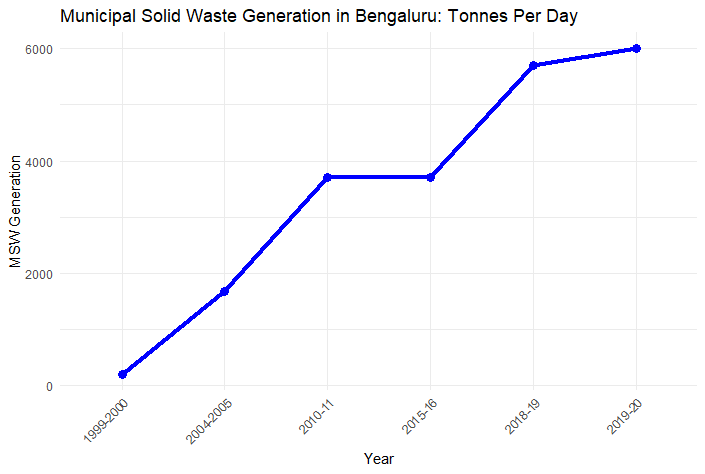

Below is a comparison of the rate of waste production from 2000 to 2020:

Urbanisation has led to excessive levels of waste production. However, the exponential waste growth in Bengaluru surpasses that of other cities. From 200 tonnes of waste generation per day (TPD) in 2000, waste production reached 6,000 TPD in 2020 (see Figure 2). This holds significant implications for the city’s future expansion and growth. According to Vishwanath Srikantaiah, a water conservation expert, many sewage treatment plants (STPs) in Bengaluru remain underutilised, and location is one of the contributing factors for this.

Need for an integrated approach

The state’s waste treatment issues must also be looked at within the national context. The Union government has successfully reached its goals of achieving an Open Defecation Free (ODF) in India. Yet, its performance in waste management is not up to the mark.

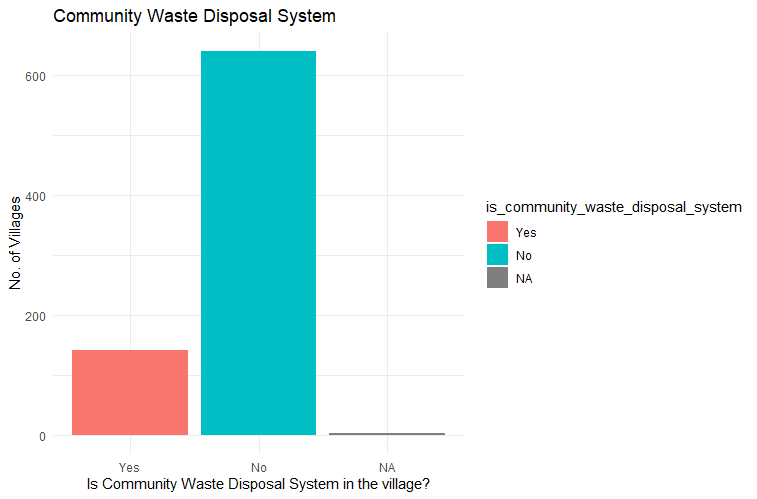

A crucial facet of the Swachh Bharat Mission (SBM) is Solid and Liquid Waste Management (SLWM), aimed at enhancing cleanliness, hygiene, and overall quality of life. However, a sobering fact emerged upon scrutinising the Mission Antyodaya data for Bengaluru urban villages. I looked at the community waste disposal systems across Bengaluru gram panchayats and found that only 141 (18%) of the total 780 panchayats have a disposal system in place.

Time is ticking for Bengaluru. With a decadal population growth of over 47%, the issue of waste management will only get worse in the city. As Bengaluru’s boundaries expand, the celebratory spirit of ‘Brand Bengaluru’ and global investments also mark the exponential rise in population and waste generation.

If the current government wants to account for the future of urbanisation in the city, it must create a robust municipal infrastructure that prioritises proper drainage and waste management. The former is also a key concern to fulfil Sustainable Development Goal 6, which calls for ‘Clean Water and Sanitation for All’. The state must recognise that these services must be provided ‘for all’ for the sustainable urbanisation of Bengaluru.