Buying your own house represents the pinnacle of a person’s success. Own housing represents stability and growth and a peaceful life, either individually or with a family. However, I have seen that the dream of being a homeowner is increasingly becoming elusive for many families, particularly in the capital city of Delhi, where I live.

Delhi as an integrated economic powerhouse offers rich employment opportunities for everyone. Thousands migrate to Delhi each year with the hope of a better life and settle to have a fresh start. Many young students and professionals, who wish to enter the middle class, see home ownership as their ticket to upward mobility and a chance to give their children a better life.

However, Delhi faces a chronic housing deficit. Availability of affordable housing units is much lesser than the demand. Consequently, it has pushed people into substandard housing in rented flats with inadequate space, poor amenities.

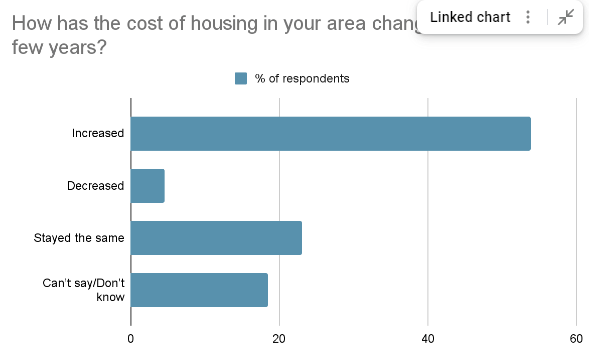

I wanted to understand the reasons behind this steep rise and how it affects homebuyers. So, I conducted a survey among voters of West Delhi to gauge their responses to the current housing market. Of the total number of 64 people surveyed, 53.8% of the respondents said that housing costs in their area had “increased” over the years while only 4.6% said that the cost of housing had decreased.

Several studies conducted in the past few years have said that housing market inflation in Delhi is unsustainable. Housing prices have appreciated by 9.3% on an annual basis between 1991–2021, according to an analysis by the Centre for Social and Economic Progress.

Read more: How the rise of brokers has changed low cost rental housing in Delhi’s urban villages

Disproportionate rise in housing costs to incomes

A year by year increase in housing prices is expected in a burgeoning city like Delhi, where population growth has not slowed down and so hasn’t the demand for houses. We know that higher demand means higher prices.

However, I observed that the problem arises or worsens when incomes do not rise proportionately. The study by CSEP states that, “at a price-to-income ratio (PTI) of 11, housing in India is more than twice as expensive as its affordability benchmark of 5.”

Per the Housing Price Index, 1 BHK apartments in December 2023 cost 26% more than in Jan 2017, 2 BHK apartments cost 19.6% more and 3 BHK apartments cost 45% more in December 2023 against the prices in January 2017. Overall, housing prices rose more than 31% between January 2017 and December 2023.

For example, in Uttam Nagar of West Delhi, the average house prices range from Rs 28-35 lakh for a 2BHK apartment. Compare this to the per capita income of a person in Delhi in FY 2023 (Rs 4.44 lakh). Prices were 7.2 times the income, again being unaffordable for an average person.

In Dwarka, a 2 BHK apartment costs a whopping Rs 1 crore, 22 times the average income of a Delhi resident. How can anyone manage to generate funds at this pace? I don’t think it is possible for most of us.

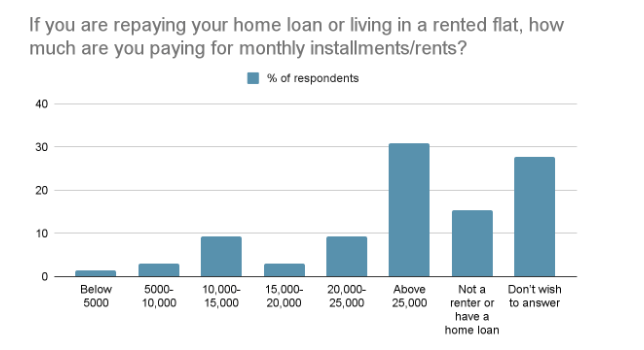

As per our survey responses, 40% of respondents paid more than Rs 20,000 per month towards home loan repayments/rent. Out of these respondents, 70% disclosed their monthly income to be more than Rs 60,000 per month, higher than the average monthly income of Rs 37,064.

Compare this to the 28/36 rule which says that families should not spend more than 28% of their income towards housing costs and not more than 36% of their income towards total debt payments.

Respondents in our survey were spending 30-35% of their monthly income on housing costs including debt repayments and rents and maintenance. Aren’t these levels of spending unsustainable for the financial health of many middle class families? How can one cope with this pressure that might go on for many years?

I also realised that the impact of housing inflation is even harder on low income families. It prevents many potential homeowners from buying houses due to the amount required to spend each month.

Expectedly, I found that 12.3% of respondents said they would wait for prices to fall in their area before buying a new house. Also, more than 25% of respondents said they would rather buy a home outside of Delhi.

Read more: Surging EMI burden affects affordable housing sales in Mumbai

Shortfall in DDA housing units

The reason behind such high prices can be attributed to a shortage of housing units in Delhi. According to the Unified Building bye-laws 2023, the maximum allowed number of floors in residential areas is four plus a stilt.

As the economic survey 2023 said, “Delhi’s housing market is complex where land, the basic input to housing, is under the control of the Central Government and has the responsibility of acquiring and developing lands through Delhi Development Authority. There is a wide gap in the supply and demand for housing which is largely met out by the unregulated private sector. The housing scenario in Delhi is manifested through the features like substantial housing shortage, large number of households without access to any shelter or shelter within one room housing units etc.”

For Delhi residents like me, DDA flats have been the hallmark of the government’s push to more affordable housing. It has met with mixed responses from the people. While our respondents rated DDA flats good/fair on parameters such as access to public transport, appropriate number of bedrooms and proper water/electricity utilities, they rated them poor on parameters such as condition of roads, greenery and aesthetic and parking.

Affordable housing as a concept is often equated to appropriate or moderate prices. However, it should also be a pleasant experience for the homeowner, which can come from amenities such as connectivity, adequate water supply, access to schools, hospitals and open spaces.

The failure of affordable housing schemes by the DDA in areas like Narela where 40,000 units lie vacant underscores the need for governments to balance the low housing prices with access to infrastructure, amenities and overall connectivity.

Unregulated private sector housing

An unregulated private sector and lax enforcement of zoning regulations has led to the creation of many informal settlements (jhuggi-jhopri areas) and unauthorised colonies, where poor quality housing is built in violation of norms.

The report by CSES also highlighted the fact that “lack of credible and rigorous land use planning and implementation, leads to a constrained and unpredictable supply of land”.

This allows many real estate developers to increase prices to inflate their profits.

Housing as a larger urban planning goal

Housing is a basic human right of each and every citizen. As the city continues to urbanise, I believe it is crucial that policymakers provide affordable housing for all residents.

One of the solutions could be, allowing new housing projects to have a higher number of floors in Delhi, so as to accommodate more housing units in a given plot. However, any measure must address regulatory hurdles and land availability challenges.

More importantly, it must promote sustainable urban design, and ensure equitable access to basic amenities. Without these the ultimate dream of owning a house will not bring true satisfaction to thousands of Delhi residents, who strive for it every single day.

The author is a member of the cohort of the Civic Journalism Training Programme, jointly hosted by Oorvani Foundation and Youth ki Awaaz. This article was produced under the programme.