“Irrespective of them (Ola-Uber) increasing or decreasing the prices, our commission margin doesn’t change, we haven’t made any profit from the surged charges on these platforms,” says 28-year-old AS Mantelingu, an auto driver with Snehajeevi Chalakara Sanghatane.

Mantelingu’s commission is dependent on the trip essayed from point A to point B, out of which the ride-hailing apps would take 25% of his earnings per trip. He gets money only for picking up and dropping commuters, not the surcharges imposed by the apps during peak hours or rainy days. Mantelingu complains of ‘dead mileage’, which is the cost of driving to the place of the pick-up that he is uncompensated for.

With a sparsely connected public transport system and rising fuel prices that make owning a private vehicle unaffordable in the city, ride-hailing apps like Ola, Uber, and Rapido serve as a lifeline for daily commuters and a source of livelihood for the driver partners on them.

Ravi KS, a resident of Uttarahalli who commutes to Majestic on a daily basis, registers a drop in the current prices. “Prior to the fares being questioned, I would pay Rs180-Rs190 for 7.8 kms, but now that has reduced to Rs 150- Rs 170,” he says, adding that if it wasn’t for ride-hailing apps, he would have to walk for quite a distance to hail autos. However, he also voiced concerns about bogus penalties being levied by these platforms and then manually having to dispute those charges.

Government clamps down

However, this came to a standstill when the Karnataka government earlier this month imposed a ban on the platform aggregators upon complaints of hiked fares from commuters. The issue gained traction when Member of Parliament Tejasvi Surya echoed the concerns of the commuters and penned a letter to Chief Minister Basavaraj Bommai. He wrote the commuter must not be charged above the government prescribed rates.

In this first part of the series, we unpack how platform aggregators like Ola, Uber and Rapido invoked the ire of drivers, commuters and the Transport Department.

Read more: When Uber, taxi drivers went to court

Events leading up to the ban

According to auto unions, the ride-hailing apps started operations for cabs in 2014 and attached autos to their fleet in 2017 without authorisation. “Then, while the government fares were set at a minimum of Rs 25 for a distance, Ola would offer us competitive prices like Rs 40 for the same distance,” claims Adarsha Auto and Taxi Drivers’ Union’s president M. Manjunath.

During their initial operations, Ola and Uber did offer several monetary incentives and promo codes for customers and commuters alike to capture the market. “The apps get the customers used to them and then manipulate the prices,” says Kaveri Medappa, a University of Sussex researcher studying app-based workers in Bengaluru.

While the fares have dipped post the interim order, there is no telling how long this will last because of the lack of fare-based regulations. A senior official at the Transport Department, on the condition of anonymity, said they will keep an eye out in case the fares surge again.

Read more: Bengaluru’s auto drivers have a love-hate relationship with ride-hailing apps

Tanveer Pasha, the President of Ola Uber Driver’s and Owner’s Association, questioned the aggregators on the imposition of fines. “When autos would function independently and they sought an additional Rs 10 or Rs 20 from the commuters, the cops would fine them. Now how are they allowed to charge so steeply for autos?” he says.

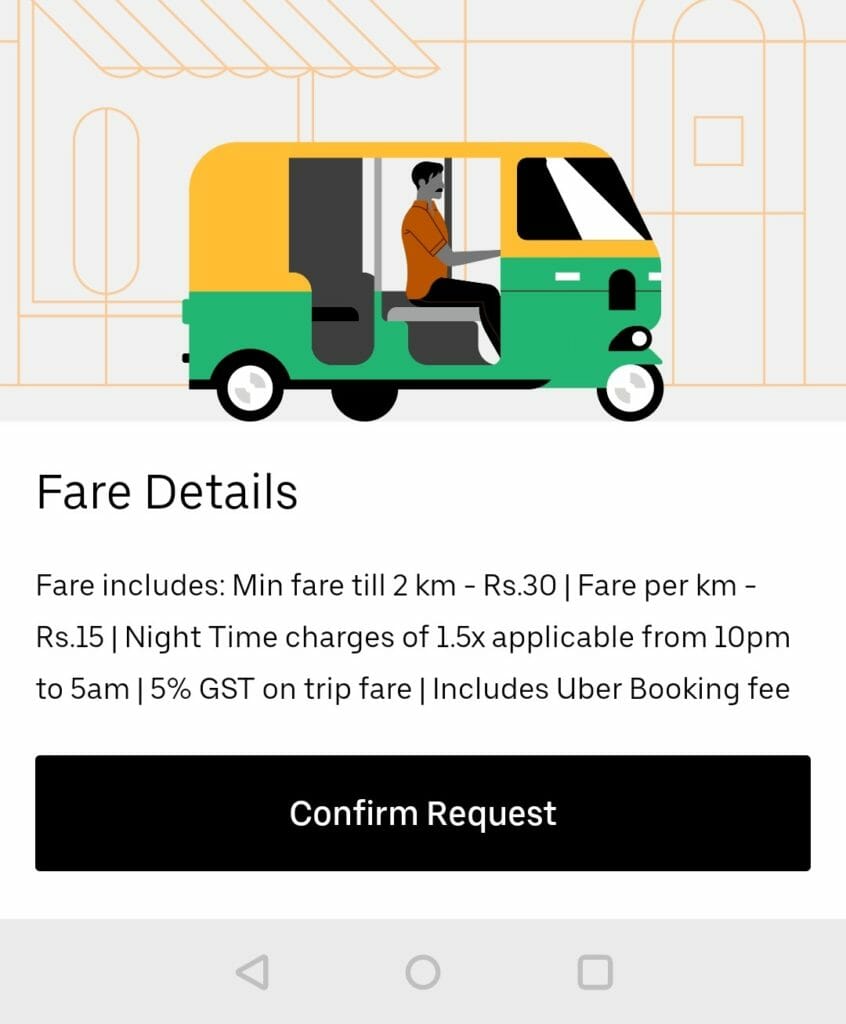

The aggregators came under the radar when they charged nearly Rs 100 per 2 km (sometimes for less than 2 kms, according to news reports) while the rate fixed by the government is Rs 30 for the same distance. The drivers and unions attested that despite the surged pricing, the drivers were paid the standard amount and not the hiked one.

“We acted after we received complaints from commuters,” said the government official. When asked about the allegations of labour exploitation levelled against the cab aggregators, the official said the department would take action against the aggregators upon a formal complaint about the allegation being registered. He did not specify whether they have received such complaints in the past or have taken action against them.

Legal challenges

The aggregators had applied for a licence to operate under Karnataka’s On Demand Transportation Technology Aggregators Rules in 2016, which was passed by the government to “ensure a greater integrity of process and operation of the on-demand transportation technology aggregator platforms.” The validity of this has been called into question as this allowed them to only operate cabs and not autos. Considering this, their claim for renewal of the same has been put on hold by the transport authorities since 2021.

On October 12, the state government cited the absence of a licence to operate autos as one of the reasons for imposing a ban on the aggregators. The transport department invited fresh applications from Ola, Uber, and Rapido seeking to aggregate autos.

Through an interim order, the Karnataka High Court on October 14th allowed the ride-hailing apps in question — Ola and Uber — to levy an additional 10% charge over the standard rates fixed by the star government, which GoK is yet to fix as per the law.

But why does it seem like private companies have more power than the state agency? The second part of the story will detail the action or the lack thereof on the transport department’s part to regulate the aggregators and explore the viability of state-backed ride-hailing applications.