A study by ActionAid Association found several problems with the sewage treatment plants (STPs) managed by Bangalore Water Supply and Sewerage Board (BWSSB). The quality of treated water is not being monitored at STPs despite it being mandatory, as per the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB). The study raises doubts about the efficacy of BWSSB’s STPs; the findings can be read in Part 1.

Worryingly, even the functional BWSSB STPs appear to have several issues. The ActionAid report highlighted that BWSSB had lower water quality standards compared to the Karnataka State Pollution Control Board (KSPCB), and was completely ignoring certain pollutants. Moreover, treated water from model STPs, such as the Jakkur STP, were found to still contain dangerous pollutants.

Impact on lakes

It is well known that lakes in Bengaluru are heavily polluted because of untreated sewage flowing into them. BWSSB had claimed that by 2025 all lakes in Bengaluru would receive treated water. The agency currently operates 33 STPs, which can treat up to 1535 mld of sewage.

Treated water from some of the STPs are released into the lakes. For instance, water from the Jakkur STP flows into Jakkur lake and the Sarraki STP flows into Sarraki lake. Treated water from the Koramangala and Challaghatta valley is carried to lakes in the neighbouring districts, such as Kolar.

However, several reports have pointed out that BWSSB-run STPs do not always function as they should. A study by researchers from Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and the Environment (ATREE) in 2016 found that the Vrishabhavathi valley STP, the city’s oldest sewage treatment plant, was not functioning at full capacity. This resulted in sewage and effluents entering the Vrishabhavathi river and flowing into Cauvery.

Untreated wastewater impacts wetland flora and fauna, as well as lake dependent economies like fisheries and livestock grazing. STPs are thus vital for treating the city’s waste.

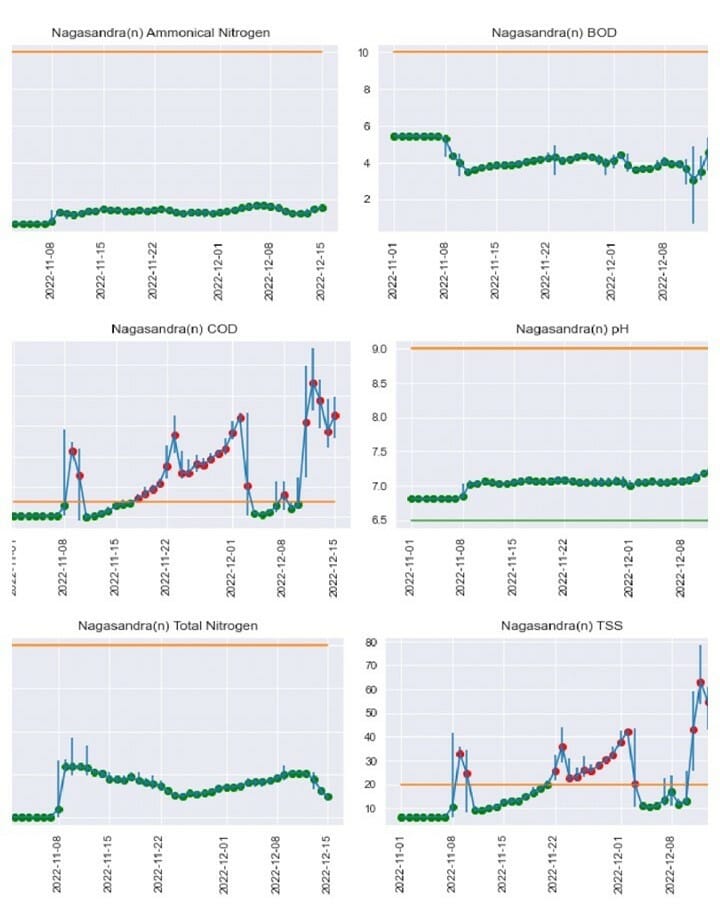

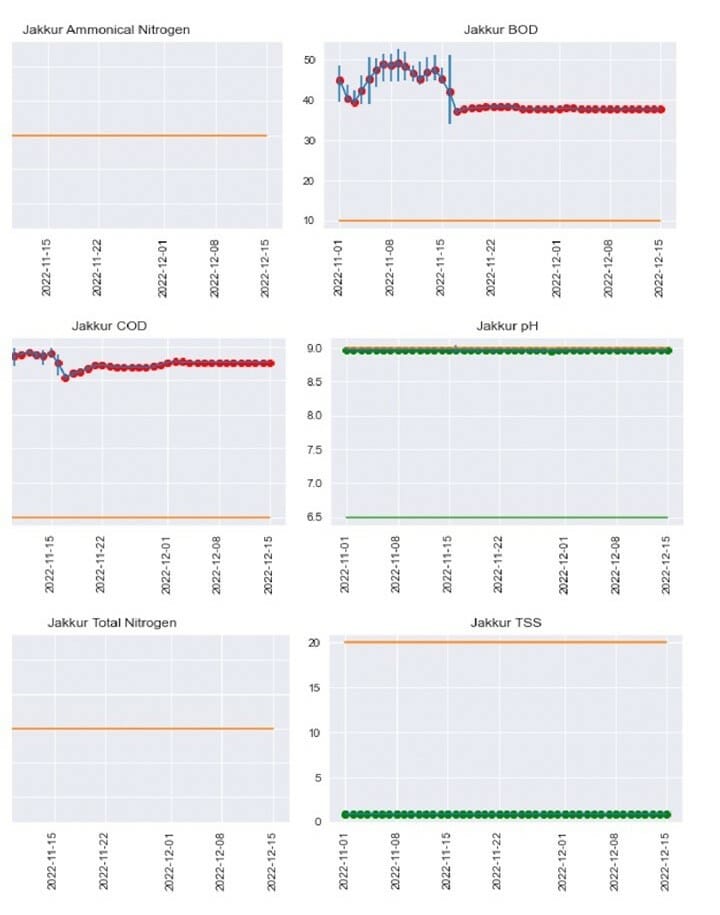

To ensure that STPs are functioning well, BWSSB is supposed to measure water for seven parameters: Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD), Biochemical Oxygen Demand (BOD), Total Suspended Solids (TSS), pH, Ammonical Nitrogen, Total Nitrogen and faecal coliform in the treated water. The CPCB sets the safe lower and upper limits for these parameters. If these limits are breached, the treated water may be considered unsafe for certain activities.

Read more: Can citizen groups maintain Bengaluru lakes? Legal tussle continues

“Many BWSSB STPs are manged by third party contractors. Regular monitoring of treated water quality is one way to ensure that they are doing their job properly,” explains Priyanka Jamwal, a researcher and fellow at the Centre for Environment and Development at ATREE. Priyanka has not seen or commented on the ActionAid study, but explained why different parameters need to be monitored and how they affect human health and biodiversity.

The STPs, managed by BWSSB, have sensors which are supposed to monitor the treated water quality to ensure that these parameters do not breach safe limits. Data from these sensors are transmitted to an online portal.

BWSSB has lower standards for water quality

Raghavendra Pachhapur, senior project lead at ActionAid Association, monitored data on the BWSSB online portal for 31 of these STPs for 45 days from November 1st to December 15th last year. He found that BWSSB had set higher maximum limits for some of the parameters compared to the pollution control board.

While the pollution control board has prescribed that TSS should be limited to <10 mg/l, BWSSB has set the upper limit to <20 mg/l, which is double the safe limit. The agency has also slightly increased the upper limit for pH. Moreover, despite the pollution control board’s mandate, BWSSB has not set up the STPs to monitor faecal coliform, which are bacteria found in faeces.

Faecal coliform in water indicates the presence of disease carrying microbes. While raw sewage has high levels of faecal coliform, the pollution control board mandates that treated water used for agriculture and wildlife be less than 100MPN /100mL. For water treated for drinking or swimming, faecal coliform levels have to be zero.

“It is important to monitor faecal coliform especially if the water is being used for irrigation where farmers will come in contact with the water constantly,” explains Priyanka.

BWSSB STPs have been inefficient in ridding water of faecal coliform in the past. “If they don’t measure it at all, we can’t know about the quality,” points out Raghavendra.

Treated water from 11 of the 31 STPs exceeded the safe upper limits for one or more of the contaminants. The Vrishabhavathi valley STP exceeded the safe limits for all six parameters; the treated water from this STP had unsafely high levels of Total Nitrogen for up to 15 days.

The old and new Nagasandra STPs, located near the Madavara Kere, also exceeded the safe limits of all six parameters. The Nagasandra (new) STP exceeded safe COD and TSS levels for 24 of the 45 days of the study period.

Jakkur, Sarakki lake receive poor quality water

Surpisingly, STPs that are attached to model lakes like Jakkur and Sarakki appear to be performing the worst. Treated water from the Sarakki STP exceeded safe levels of TSS for eight days and pH for 42 of the 45 days. Sarakki STP also did not monitor levels of Ammonical and Total nitrogen at all. The Jakkur STP exceeded COD and BOD levels for 34 of the 45 days. The COD and BOD levels at this STP were 4-6 times the safe limits.

Such breaches have major implications for biodiversity in these lakes. High COD or Chemical oxygen demand and BOD or biological oxygen demand indicate a reduction in the total dissolved oxygen in the water. With less oxygen to breathe, aquatic fauna like fish and native plants can die out. Similarly, high levels of Total and Ammonical Nitrogen can be harmful to fish and plants, Priyanka explains. “This can have cascading effects on the food chain affecting birds and even people,” she adds.

Raghavendra, who has previously documented incidents of fish mortality in lakes across Bengaluru, has no doubt that these two issues are connected. “Definitely, I wonder if these STPs are really functioning anymore,” he says. “I think our lakes are receiving very poor quality water from these STPs.”

Read more: Why pre-monsoon showers lead to fish kill cases in Bengaluru’s Lakes

It seems to be a fair point. Several of the ineffecient STPs, featured in this story and in Part 1, are performing very poorly as per KSPCB’s monthly lake water quality data. The state body classifies lakes into five categories from ‘A’ to ‘E’, based on how clean the water is and which activities it is fit for. Lakes classified ’A’ have water fit for drinking, ‘B’ lakes are fit for swimming, and ‘D’ lakes for fisheries and wildlife.

Jakkur lake, Allalasandra lake, Yelahanka lake, Ulsoor lake, Bellandur lake, and Varthur lake, all associated with poorly performing STPs, have been classified ‘E’, which means the water is at most fit for irrigation and industrial activities. Yet, these lakes are used by wildlife and people.

“I can’t understand why KSPCB does not take any action,” Raghavendra says. An enthusiastic birdwatcher and conservationist, Raghavendra feels treated water from these STPs should not be released into lakes until they are thoroughly checked.

The Chairmen of KSPCB and BWSSB did not respond to repeated calls for this story.