Sarsa, a small river that flows through Himachal Pradesh and Punjab, is considered a holy river in Sikh religious tradition. It was on the banks of Sarsa that Guru Gobind Singh’s Khalsa Army fought the Mughals. Though the Khalsa army lost that battle, its effect was far reaching. It led to Guru Gobind Singh’s separation from his family and the martyrdom of the Guru’s four children. To avenge their deaths, Banda Bahadur, a disciple of Guru Gobind Singh who was especially sent by the Guru to avenge the martyrdom of his children, laid the foundation of a professional Khalsa Army, which later defeated the Mughals. The army was subsequently commanded by Maharaja Ranjit Singh who went on to create the Great Sikh Empire. With such a powerful religious heritage, it would be fair to expect that the Sarsa river and its ecosystem would be conserved and kept clean.

Sadly, the reality is just the opposite. Originating in the foothills of the Shiwalik range, Sarsa has Himachal’s biggest industrial cluster at Baddi, Barotiwala, and Nalagarh located on its banks, comprising over 1000 industrial units mainly engaged in manufacturing pharmaceuticals and textiles. Of the cluster’s 1000 units, 900 are classified as orange (Pollution Index Score between 41 to 59), and 83 units as red (pollution Index Score above 60) (The Pollution Index is a categorization of industries by Government of India on the basis of their pollution load).

Industrial discharge from the Common Effluent Treatment Plant along with direct effluent discharge by the industries, dumping of untreated sewerage and garbage, along with unchecked sand mining has turned the Sarsa into a dead, toxic river.

Critically polluted

Sarsa had been declared one among the seven ‘critically polluted rivers’ of Himachal Pradesh by the Central Pollution Control Board in its September 2018 report titled “River Stretches for Restoration of Water Quality”. Subsequently the state set up a River Rejuvenation Committee, with a mandate to identify the source of pollutants and come up with a plan to clean it up. But that has had little effect. On July 5, 2019 thousands of dead fish were found floating in the river below Jagatkhana in Nalagarh.

Though fish mortality is not new during the rainy season, when most industries shut down their effluent treatment plants, the sheer numbers on this occasion took everyone by surprise. The culprits were two industrial units, Jay Bee Industries, a transformer manufacturing unit and another small scale unit engaged in washing of chemical drums. “We immediately shut down these units,” said Aditya Negi, Member Secretary HP State Pollution Control Board. “They are now back in action after ‘corrective measures’ were taken by them”.

On August 28th, a delegation of Naroa Punjab Manch, an umbrella organization of 50 NGOs involved in ensuring clean river water met the Chief Minister of Himachal Pradesh Jai Ram Thakur to urge him to check pollution in Sarsa river. Thakur assured them all help in this regard. But there has been no change in the river’s critically polluted status.

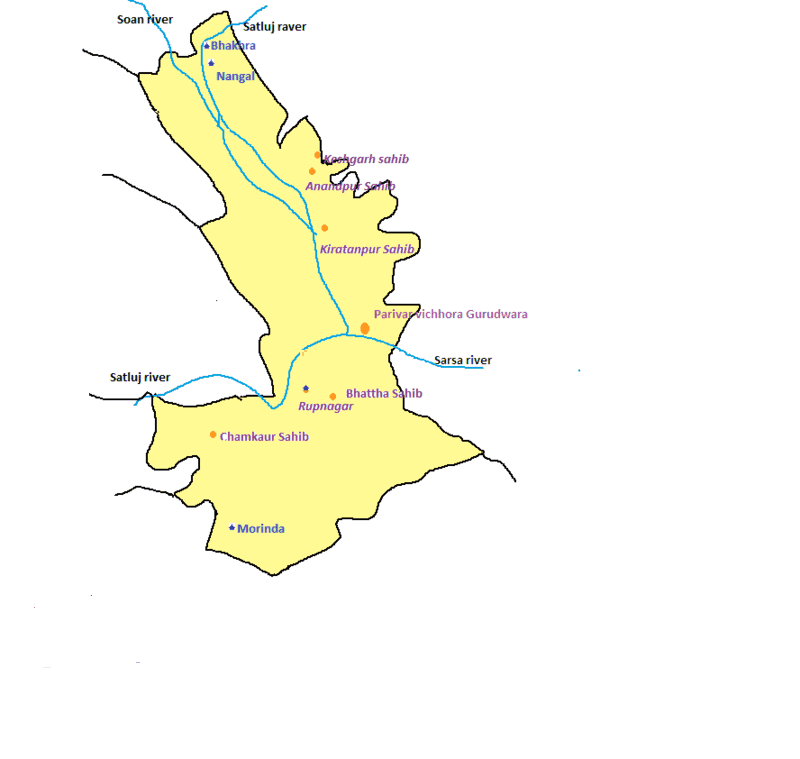

The sad story of the Sarsa river does not end here. The highly polluted river joins the Sutlej at Taraf village in Rupnagar district of Punjab, the first major point of discharge of effluents into the Sutlej, the lifeline for over one crore citizens in Punjab and Rajasthan. As per a Punjab Government document titled The Action Plan for Clean River Sutlej, the river carries Class B water (not fit for human consumption or irrigation of crops. Class B recycled water can be used to irrigate sports fields, golf courses, and dairy cattle grazing land) as it enters the state.

It turns into Class C water (recycled class C water can be used for livestock grazing and fodder and for human crops grown over a meter above the ground and eaten raw such as apples, pears, table grapes, and cherries) as the river crosses the Nangal-Ropar Belt in Hoshiarpur district.

It then becomes class E water (not fit for any human use) after the confluence of Buddha Nullah downstream of Ludhiana.

The water quality improves to Class D (recycled Class D water fit only for non-food crops) at Nakodar, near Jalandhar (upstream of the confluence of East Bien or Chitti Bien (as this stretch has no major source of pollution). After the confluence of East Bien (Chitti Bien) tributary with River Sutlej at Gidderpindi in Jalandhar district, the quality again becomes Class E.

River Sutlej is one of the fastest flowing rivers in the world. It originates from the Mansarovar lake in Tibet and cuts across the Himalayas, covering a distance of 1450 kilometres in India before crossing over to Pakistan. In Punjab, it covers a distance of 440 kilometres flowing through the districts of Ropar, Ludhiana, Jalandhar, Kapurthala, and Ferozepur. The highly polluted waters of the Sutlej river are used both for irrigation and drinking purposes in Punjab.

The extent of the pollution caused in Sutlej in Punjab can be gauged from the fact that the state disposes around 2000 kilolitres of sewage in the river per day, apart from the huge amount of industrial effluents mainly through Buddha Nullah in Ludhiana, which virtually renders it a dead river as it crosses the city.

The health hazard

“The untreated industrial effluents and municipal waste of Jalandhar is a major cause of pollution of the Sutlej,” said Daya Singh Pannu, an aide of Sant Sukhjit Singh Seechewal, the man who single handedly, with the support of villagers, cleaned up a highly polluted Kali Bien (roughly translated as black tributary). “Earlier, Jalandhar had two drains, the Kala Sangya drain and Jamsher drain, meant for carrying rainwater into the Sutlej. Now, rainwater has become secondary, all they carry is highly toxic poisonous matter, causing Class E level pollution in the Sutlej waters.”

These two drains disgorge their effluents into the East Bien or Chitti Bien tributary, around 10 kilometres upstream of Harike Pattan barrage, located at the confluence of river Sutlej with Beas and is the originating point of the Rajasthan Feeder Canal, which crosses into Rajasthan passing through Sirsa district of Haryana.

The highly polluted waters are carried through canals into the Malwa belt (South Western Punjab) where these are used extensively for irrigation and drinking purpose leading to the highest incidence of cancer and kidney diseases in India.

“In the last seven years we have seen over 22,000 cases of cancer at Guru Gobind Singh Medical College and Hospital at Faridkot alone,” said Punjab’s Kotakpura legislator Kultar Singh Sandhwan. “You can well imagine the overall impact of the pollution in the entire Malwa belt”.

The Rajasthan Feeder Canal traverses seven districts of Rajasthan, Sriganganagar, Jodhpur, Jaisalmer, Hanumangarh, Bikaner, Churu, and Barmer – places with very high incidence of cancer, hepatitis, and kidney diseases. Says Mahesh Pediwal of Tapovan Trust: “In districts like Sriganganagar and Hanumangarh, we do not have any other source but the canal water for drinking purpose. People know they are at a risk of contracting diseases, but are helpless.”

Central funding needed

The high level of pollution has put over one crore lives at stake in Punjab, Haryana, and Rajasthan. Says K S Pannu, Punjab Secretary, Agriculture & Soil Conservation and Mission Director, Tandrust Punjab and Commissioner, Food and Drug Administration and Director, Environment and Climate Change: “It’s a huge problem we are facing. But it cannot be solved in one day.” Pannu is the man behind the well drafted Sutlej Action Plan and responsible for its implementation. “The Government is spending Rs 20,000 crore on cleaning the Ganga, and we are not seeing any results. In Punjab, we are taking effective steps to clean up the Sutlej, but we are facing severe financial constraints. We need Rs 1500 crore for the clean up, but the money is not forthcoming from the Central Government.”

The Sutlej Action Plan released on February 11, 2019 gives the details of the steps to be taken to clean up the river over the next two years. The plan was created after the National Green Tribunal slapped a fine of Rs 50 crore on the Punjab Government over river pollution.

Pannu said that the Centre gave the state Rs 650 crore for air pollution. “We have used this effectively. We have seen significant improvement in this area. They need to replicate this in water pollution as well”. But the Centre is giving funds only for setting up ETPs and STPs under the Amrut Yojana, said Pannu. “The problem has been taken head on by the state government, but everything needs funds. We involved various companies including TCS, L&T, Engineers India who gave a cost estimate of Rs 1500 crores. It is difficult for the state government to come up with this amount in one or two years. Just like the clean up of Ganga, we need funds under special purpose vehicle for Sutlej.”