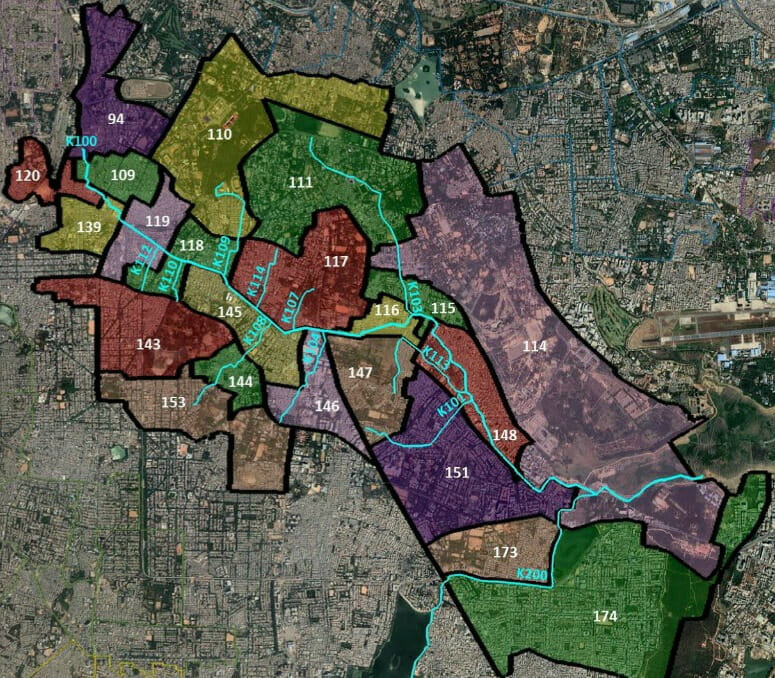

The K-100 stormwater drain cuts across 23 wards in the city as it traverses from its source near Majestic Bus Stand to its destination – Bellandur Lake. The geographies of these drains and its surrounding areas serve as important starting points in understanding city planning and the context of urban floods.

The ‘K’ in the K-100 stands for the Koramangala Valley and the ‘100’ denotes that it is the first primary stormwater drain (SWD) of the valley. The K-100 has multiple secondary and tertiary drains, numbered K-101, K-102 etc. intersecting at different points. The drain serves a catchment area of 32 square kilometres.

I walk through the different areas that were former tank beds and sites of historical significance, some still located close to waterbodies. I take the camera to photograph the scenes unfolding, to record the goings on. It is also a quest of knowing the unknown, of reimagining stormwater drains, of tapping into the areas that are embedded in our city, of occupying the space around it in its present avatar and learning about the neighbourhoods, far removed from our daily lives (at least some of ours!), unless there are floods. It is a way of experiencing – the identity of the stormwater drains, the power – privilege vs the spectatorship – participation dynamics of local communities and relooking at places hidden from our everyday view.

Tracing the route of the K-100 stormwater drain

In October 2021, standing on the walkway of the Shantinagar drain, I observed the frenetic pace at which the workers went about the K-100 drain work. Some were carrying huge concrete slabs, some were working on the pipe connections, others were tending to the plants, some were cementing the cobblestones. The Shanthinagar bus terminus was built, in 2010, at a cost of Rs 108 crores. The area has always been in the news, with issues of water logging and flooding.

The K-100 Citizen Waterway Project is an important infrastructure project that aims to restore stormwater drains to its original avatar of carrying storm water. As the CAG report had pointed out, the 41 waterbodies that existed in the Koramanagala valley (prepared through field survey during early 1990s) were reduced to eight by 2008, indicating the severity of land conversions. The report also noted that the total length of drains was 112.24 kilometres, which was reduced to 62.84 kilometres and the length of two drains that merged into Bellandur was reduced from 338 metres to 136 metres between 2008 and 2016.

The K-100 Citizen’s Waterway Project is being built on the premise of enhancing aesthetics and its potential of being an open public space. But the question is also about legitimacy and principles of social and environmental justice. What happens when infrastructure projects fail to deliver? What happens when there is flooding, accidents or just poor service delivery? As David Maddox puts, “A key problem for the idea of a just city is that it works well in a metaphor. Making a reality of justice is harder”. (Maddox & Lydon, 2015). How do we ensure that a project funded on public money will stand the test of time?

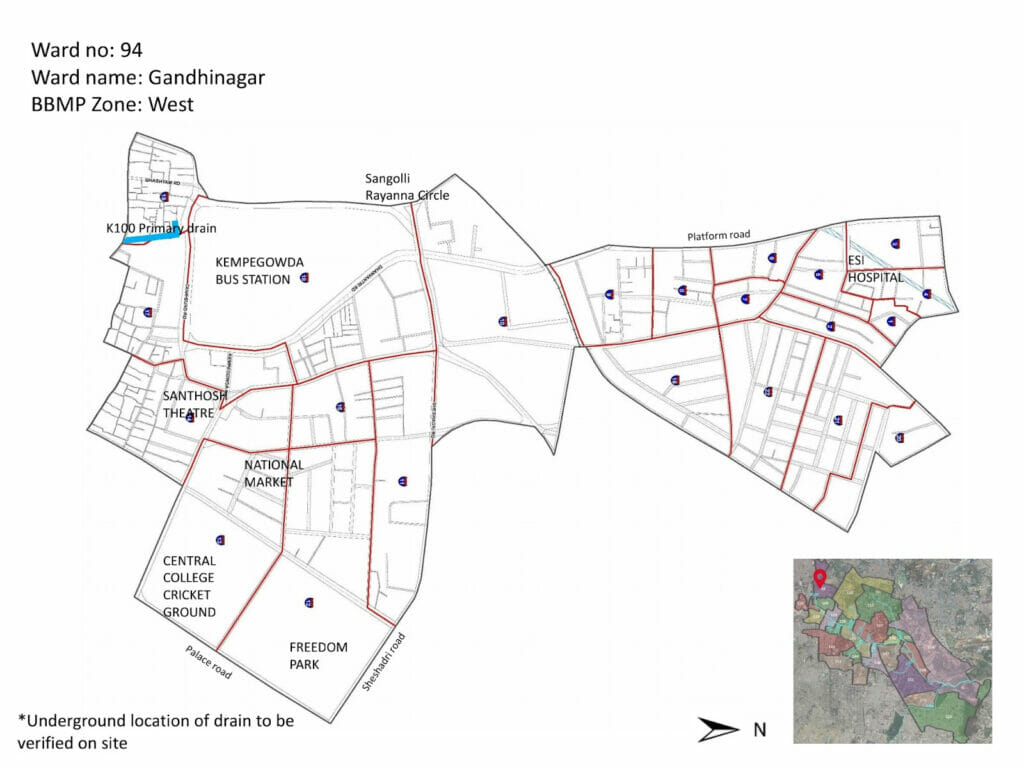

Bus terminus and shopping districts at Majestic, Cottonpet, and Chickpet

Looking for the elusive start point, I reached Shantala Silks, right opposite the Subhash Nagar Bus stand, popularly known as Majestic Bus Terminus, now called Kempegowda Bus Stand. I walked around the stretch, asking people for the drain. Finally, as no answers were forthcoming, I made my way into the store. The owner kindly offered to show me the starting point of the closed, neatly paved drain. The K-100 stormwater drain starts at Chikka Lalbagh, also called Tulasi Thota, next to Shantala Silks and is right opposite the famed Dharmabuddhi Tank in Ward 94 Gandhinagar. The Dharmabuddi tank served as a chief source of drinking water for the old city that predated Kempegowda I. The Dodda Annamma Temple, opposite the Kapali Theatre at Majestic, used to have ponds in its premises.

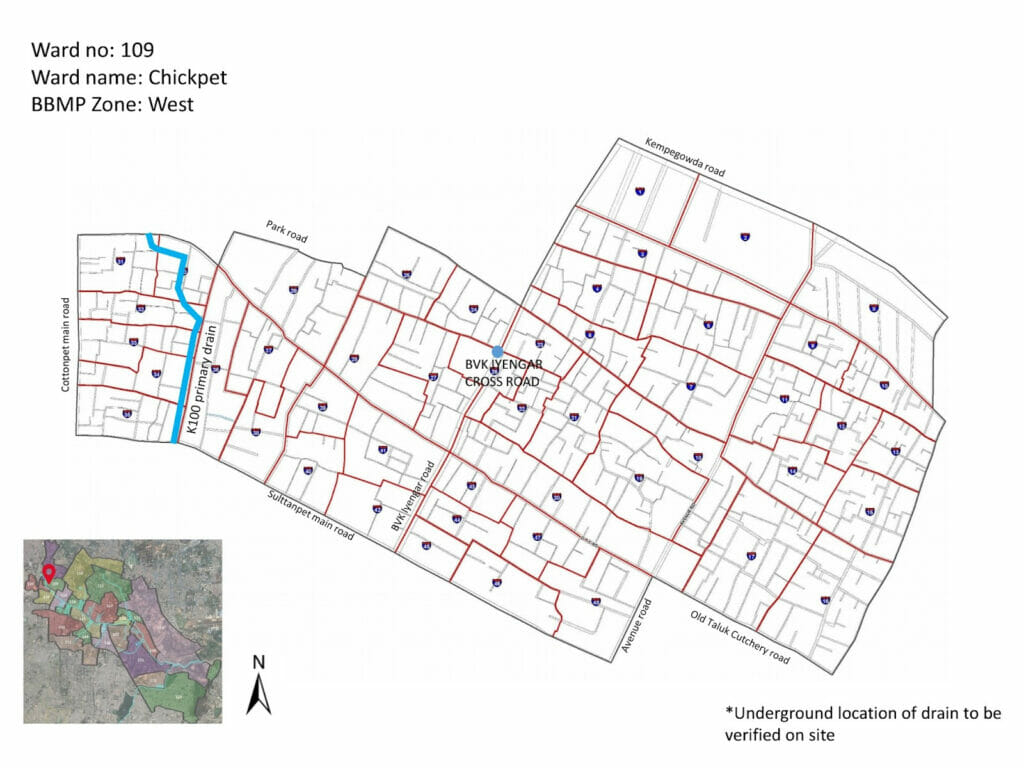

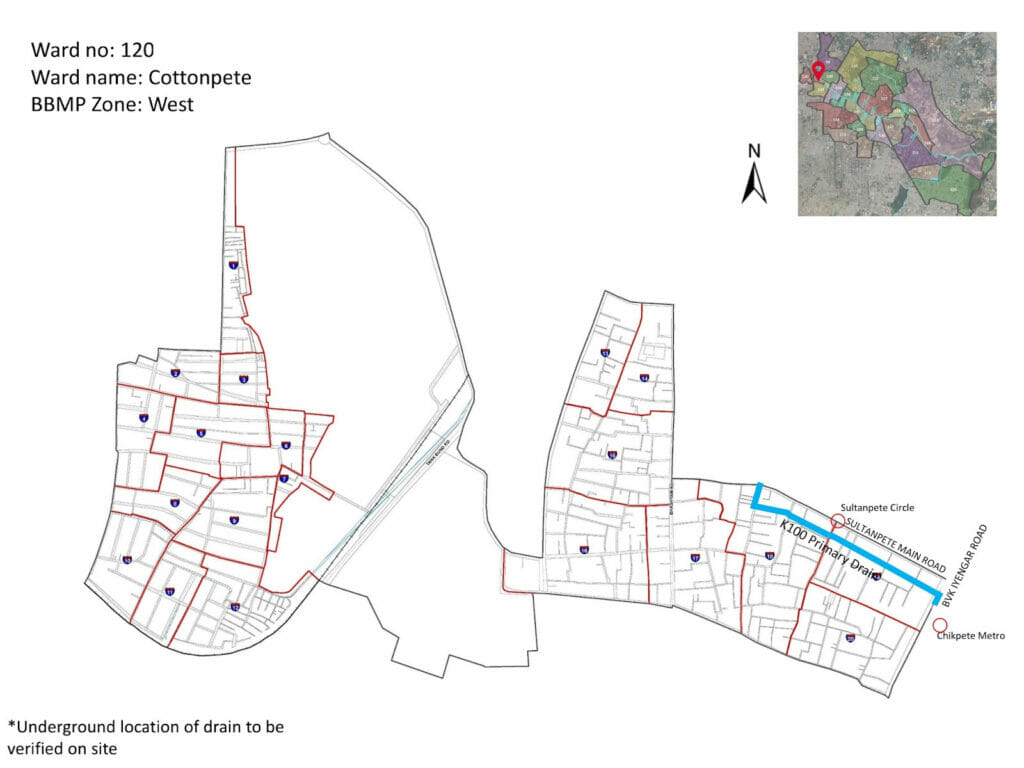

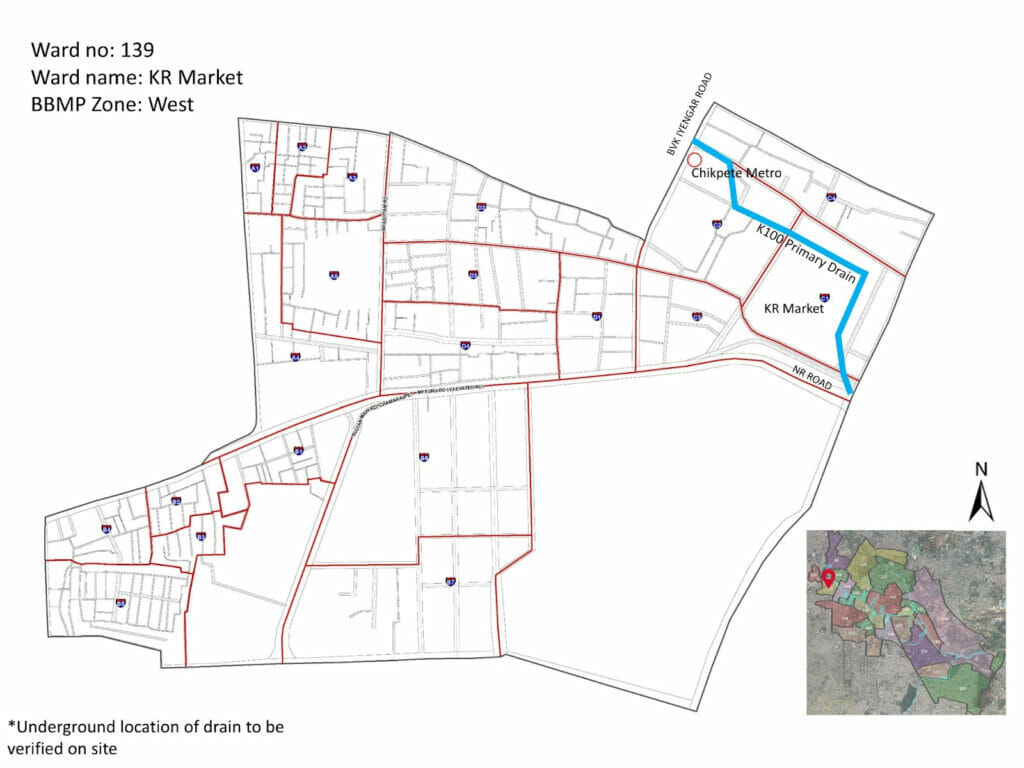

From there, the SWD snakes underground, cutting across the following wards: Ward 109 – Chickpet making its way to Ward 120 – Cottonpet (includes the bustling BVK Iyengar Road, Chickpet Metro Station) and finally resurfacing in Ward 139 – KR Market opposite the Jamia Masjid, where the K-100 Citizens Waterway Project starts. The Chickpet area suffers from a host of civic issues – from improper garbage collection, choked drains, overflowing sewer lines among others. Water logging is common in these areas even with moderate rainfall.

Walking along the old city is a revelation of sorts. The labyrinth of shops, boxed complexes, the alleyways, the temples, mosque and dargahs, the old buildings, makes for a visual treat. While I had the map of the stormwater drain, walking across these busy clusters, the display of wares, and mannequins from the buildings made the atmosphere surreal. The porters or coolies, making their way, with their loads, juggling people and oncoming traffic can leave anyone breathless.

Read more: Faulty execution in BBMP SWD works has led to floods

The sensory experience makes you forget the drains, till you speak to the shopkeepers. Then the woes come pouring out. This year’s April showers made matters worse for residents here. Why has the old pete area been neglected? SMART City work is on display everywhere, some stretches closed for white topping, some roads dug up, with cables rearing its ugly face.

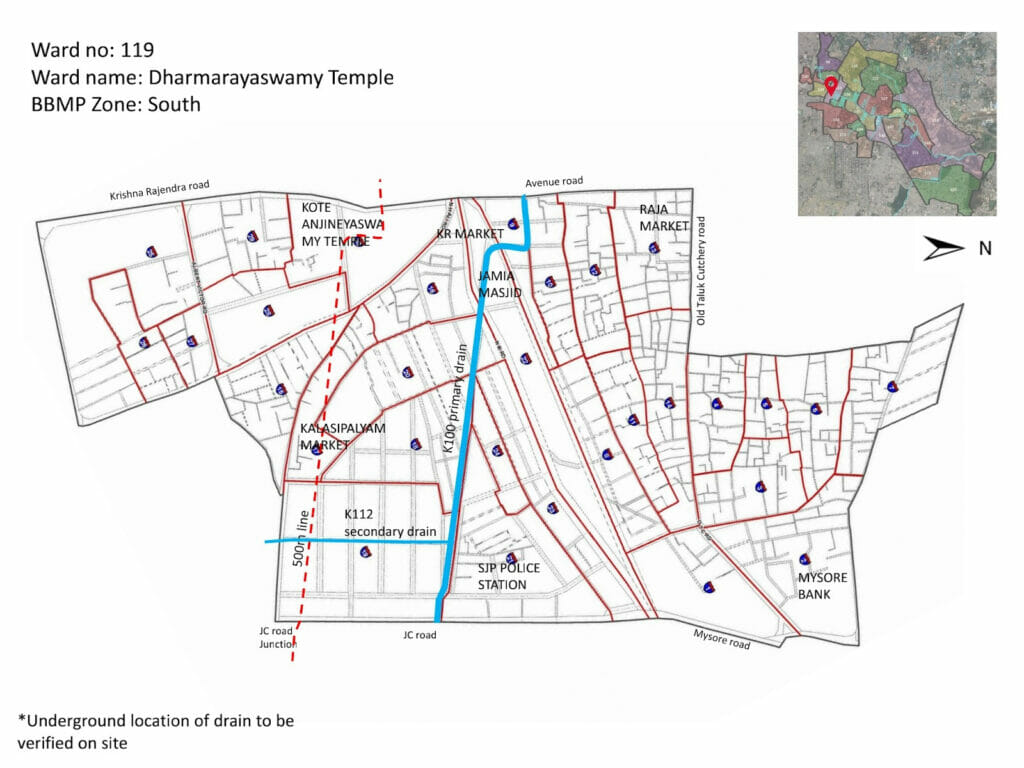

I paused and then made my way to the famous Dharmaraya Swamy temple and then on to KR Market. Everyone I spoke to said the dodd-mori (big drain) is the cause of flooding.

According to Meera Iyer, The Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage (INTACH) co-convenor, ‘The area where the market now stands was close to a large waterbody called Siddikatte that lay between the pete and the stone fort”. Author-historian Maya Jayapal too in the book, Bangalore – The Story of a city, says “the old fort and the new fort were linked by an esplanade adjoining a waterworks construction called Siddikatte”, though others refer to the tank as a kalyani.

A kindly traffic police officer pointed me to the dodd mori, opposite the Jamia Masjid. The first visit to the starting point of the K-100.

Suresh Jayaram, writes in this book Bangalore’s Lalbagh: A Chronicle of the Garden and the City, “There is no market without garden, and this market – the pete – was planned and positioned strategically to connect the kote (fort), the kere (lakes), and the thota (gardens). If one draws a connecting line between these sites – points that are laid out as a matrix or mandala – one is reminded of the ubiquitous kolams often drawn outside homes on freshly washed tar roads and cement sidewalks.”

Walking back into the market area, makes you realise that these areas are caught between the past and the present, while prompting the question how the market came to be?

Meera Iyer, writes about the story of Siddikatte: “Around the 1840s, a gentleman named Gundopanth, who had been an official in the British Commissioner’s administration, built a small agrahara on the bed of the Siddikatte tank. This tank reached a dilapidated condition during the 19th Century. But soon after the British occupation of the Bangalore fort, the battlefield was made into a public place.” In 1921, a new market building was built and named after Krishna Rajendra, the then Maharaja of Mysore.

The lakes that were

The present Kalasipalya is on the Kalasipalya Lake bed. In a 1885 map, showing the Dharmambudhi Lake and its connections, the other lakes that form part of this area near KR Market include the Mavali lake, the Karanji lake, the Lalbagh lake ( in existence), Siddapura lake, and Sunkal tank. All the other lakes have disappeared or are encroached upon, except for Lalbagh Lake, which was developed in the 1890s during the tenure of John Cameron.

The old slums of the city

A little after the JC Road multi parking lot, before you reach the signal that leads to the Bangalore Stock Exchange, are a cluster of slums Cement Hut (Colony), Ramana Gardens, KS Gardens, Papanna Gardens, Vinobha Nagar, and Rajagopal Gardens. A walk through this area, which Supriya Roy Chowdhury, author of the book City of Shadows, calls the ‘old slum’ and the residents the ‘old poor’ and reveals another side of the city. A city that is excluded and like the title of the book, a city in shadows, and highlights the stark inequalities that exist. Supriya says, “Older inner city slums represent a diversity of occupations, incomes and standard of living, although they are predominantly characterised by low incomes, multiple vulnerabilities and low levels of basic amenities.”

Read more: Lack of stormwater drain planning in Bengaluru is a risk factor for future floods

Most residents have a similar story to share: their parents had settled in the area and they have lived all their lives here. Some talk about living in rented houses, before constructing a small place that they could call their own. The residents of these areas have been at the mercy of waterlogging, poor sanitation facilities, and improper garbage collection for many years. The drain water continues to make their lives miserable, but they just move on with their lives.

As you walk your way out of the slum, onto the main road, close to the signal, is a right turn that leads you to the drain at KS Gardens. KS Gardens, in the original slum cluster, has been upgraded. The area is intersected by the SWD, whose long stretch connects Passport Seva Kendra on Double Road and further to Sudhamanagar.

K-100 through Shanti Nagar – Wilson Garden- Adugodi

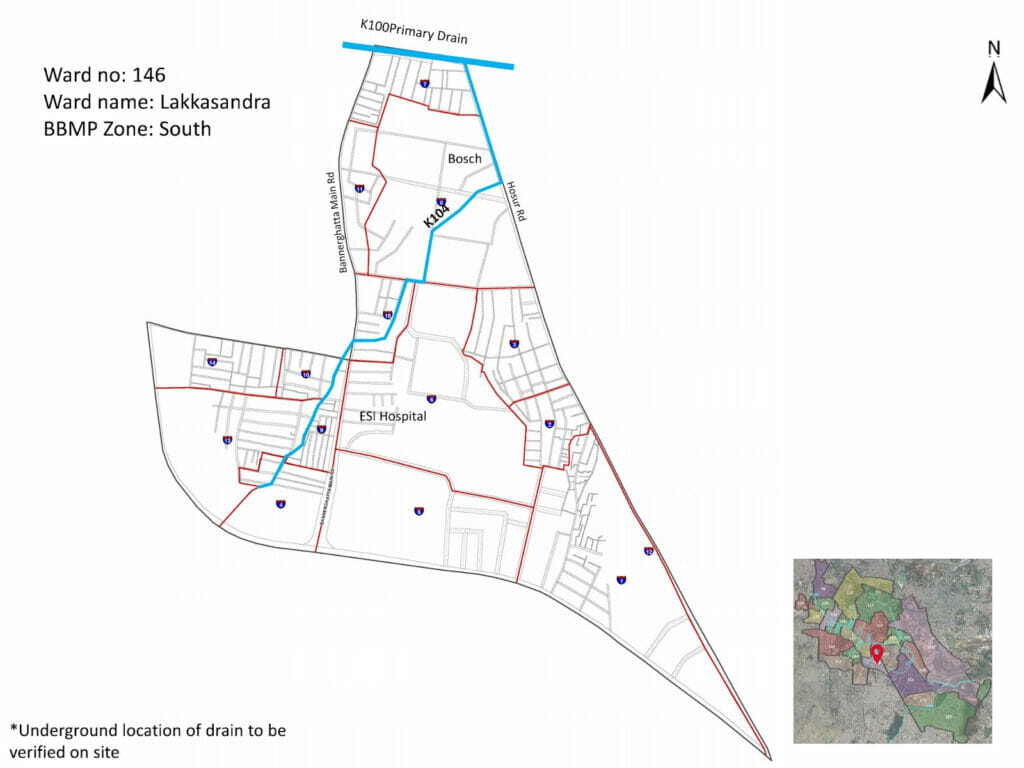

From Shanti Nagar, the K-100 continues towards Adugodi, passing through Wilson Garden/ Bannerghatta Road, also known as the Marble Market, in Ward 146 Lakkasandra. The sandra in Lakkasandra implies the presence of a waterbody.

In 2021, there was a petition submitted to the Chief Minister to restore the lake to its state. Currently, the lake area is being used as a worksite for the Bangalore Metro Rail Project. The prominent red signage “Take Diversion” displayed can be attention grabbing, but through the streets, it is garbage that rears its ugly face. But once you stop to stare at the drain towards Adugodi and the Bosch unit, it feels like time stops and all the sounds and traffic fade away.

Bosch Ltd started its manufacturing operations in India (as MICO) at the Adugodi facility in 1953, when industrialisation in the country was still at an early phase. In the chapter Industrial Pollution and Slum Dwellers written by Nico Kerkum in the book Living in India’s slums: A case study of Bangalore, edited by Hans Schenk, the author states, “Urban slums in India tend to be situated in least attractive sites, and sites close to existing industrial and service oriented workplaces for obvious reasons and gives a bit of an overview of the drain.“

There are many small scale industries here. Interestingly in 2017, Bosch and other industrial units in the area had to shut down its operations temporarily, following notice by KSPCB, for discharging treated and untreated waste into the waterbody, within the catchment area of Bellandur lake.

Marginalised parts: Rajendra nagar, LR Nagar, Ambedkar Nagar, Shastri Nagar, Samatha Nagar

As I made my way to LR Nagar, the JNNURM-funded urban poor housing behind the stormwater drain stood out. The garbage strewn around the underground bins, make for a very disturbing sight.

A back history of the place reveals that LR Nagar (LR standing for Lakshman Rao) was part of the JNNURM redevelopment plan proposed in 2005. Prior to that, from the early 1970s to the better part of the 2000s, most residents lived in temporary shacks, by the drain. A photograph of the LR nagar slum in a 2011 article in The Hindu shows the state of the slums then and the problems faced because of the stormwater drain.

Walking this stretch, you see an assortment of things, garbage auto parked at the sides, women washing clothes, children playing, dogs resting, chickens running, and the underground bins standing proudly. You will also see some wall paintings of segregation of waste at source and at one stretch an old composter.

Residents here complain of the usual problems of water logging, garbage, and the lack of sanitation. But the main issue is the stigma associated with the slum and is common for all the surrounding slums, including Ambedkar nagar and Rajendra Nagar, the slum adjacent to National Games Village.

At the stormwater drain, the earth movers were busy lifting huge concrete slabs at one junction, at the other end of the drain they were clearing silt. On the way, I spotted BBMP marshals, along with some volunteers from Let’s be the Change NGO, going door to door explaining the waste segregation process. But the problem in these areas is that of sustainability of any initiatives. Till such time that the processes are not institutionalised, the stormwater drains will always be at the receiving end.

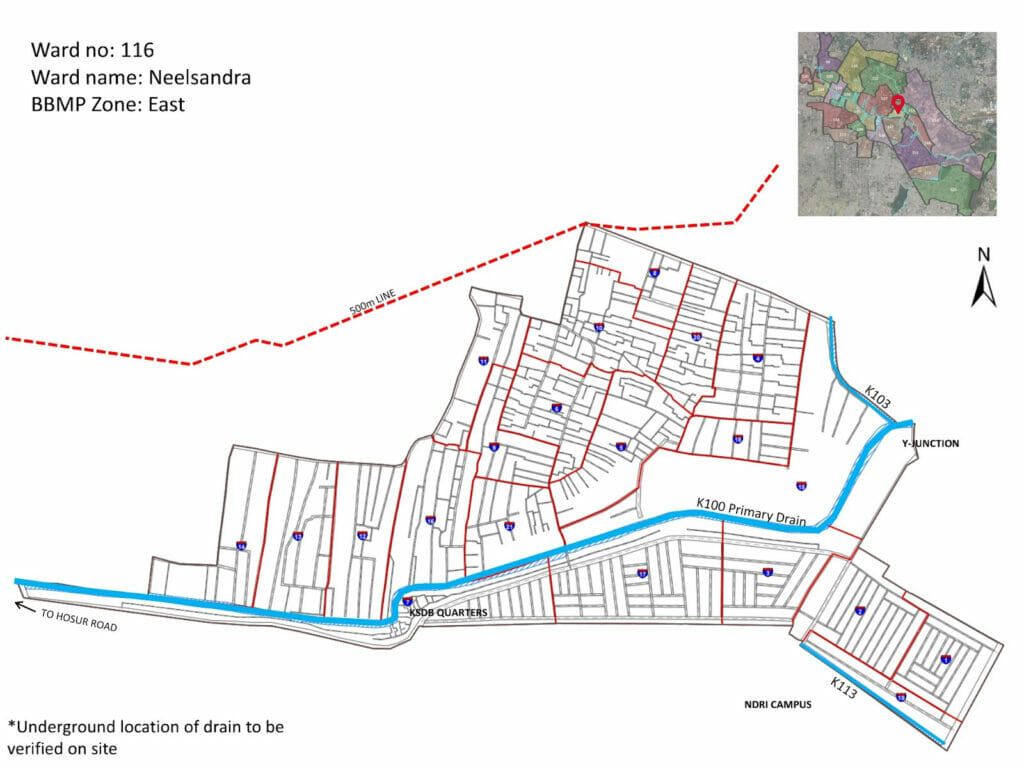

I then walked with one of the marshalls, who directed me to the road leading to the drain, and I found myself in Neelasandra. And here, you can see a Y junction. On my first visit to the drain, it was filled with an assortment of garbage, including sofa and mattress, on subsequent visits, there was improvement. I don’t know what happened to the garbage, but desilting was in full swing. I was filled with delight seeing water in the drains.

Neelasandra’s history can be traced back to the 18th century, when different armies used this village as a camping site as this village was known for its water sources. The word Neela means blue in Kannada and sandra means waterbody.

On one side you will see a Dry Waste Collection Centre (DWCC) and the Dhobi Ghat, which was moved from Vannarpet. The housing complex stands out in contrast to the LR nagar colony, in terms of visual cleanliness. The washermen’s unit located in front of the building – with washing, drying and ironing areas in front and the residential building behind has clean facilities.

The secondary drain K-103, which starts at Church Street and connects Austin Town to Viveknagar joins K-100 at this Y junction. Austin Town was built in the early 1920s when the British authorities decided to re-settle workers and lower-income residents in the aftermath of the bubonic plague of 1898. Austin Town was once Sonnenahalli lake.

Here too, there is a DWCC. But most materials are soiled and are of extremely low value. In the middle of the drain, you find a power tower. At an open stretch of the drain, cows make their way inside to drink water. On the side, you will find the underground garbage bins, with waste scattered around and crows, dogs and cows for company. On some days, you will waste pickers trying to salvage some of the plastic bags and occasional cardboard items.

The drain continues to the road parallel to Vivek Nagar Church towards Ejipura bus stop and National Games Village.

K-100 reaches Koramangala

Deccan Herald had reported that the Bangalore Development Authority (BDA) and the Karnataka Housing Board’s National Games Village (NGV) had encroached on 5.24 acres of the stormwater drain, and this had caused severe flooding on the the NGV side of Koramangala, along with adjoining localities such as ST Bed Layout, Koramangala 4th and 6th Blocks and Ejipura. The article also mentions that two water bodies in Koramangala have been completely encroached upon. In a recent article, after this year’s floods, Janaki Nair, Historian, recommended the need to revive the intertwined tank and market garden model in every locality.

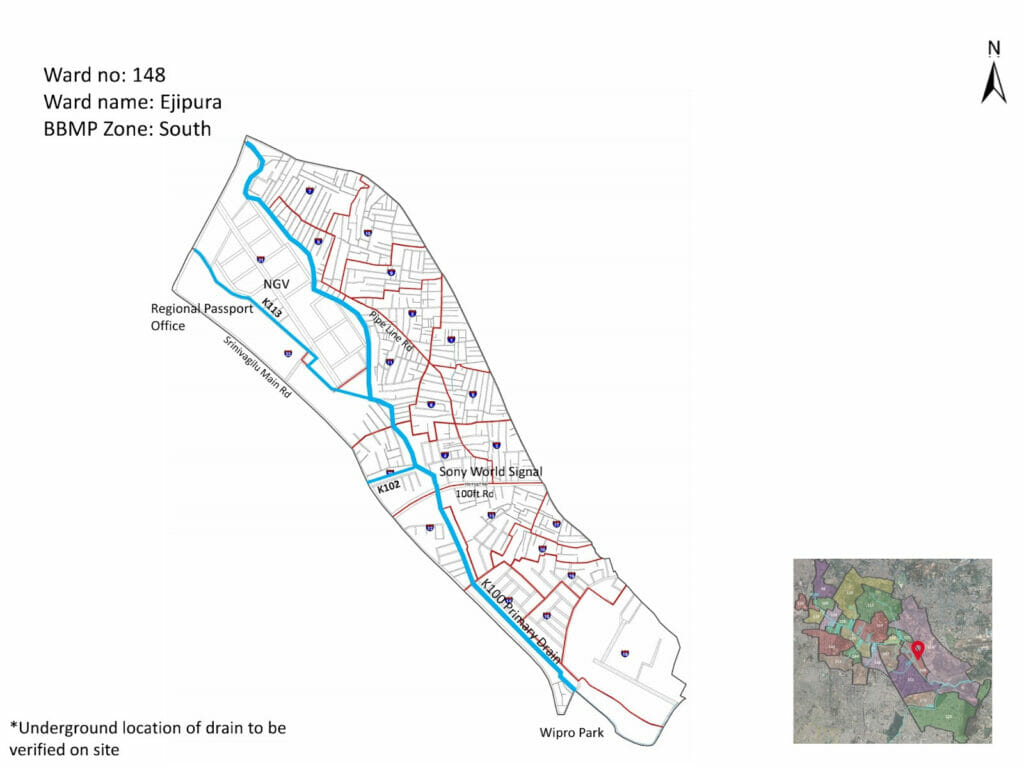

From the Regional Passport Office, another drain, the K-113, intersects forming another Y junction before joining the NGV and then the drain makes its way towards Ashwini Layout, part of Ejipura. Ejipura village was situated around the now lost Chinnagara Lake.

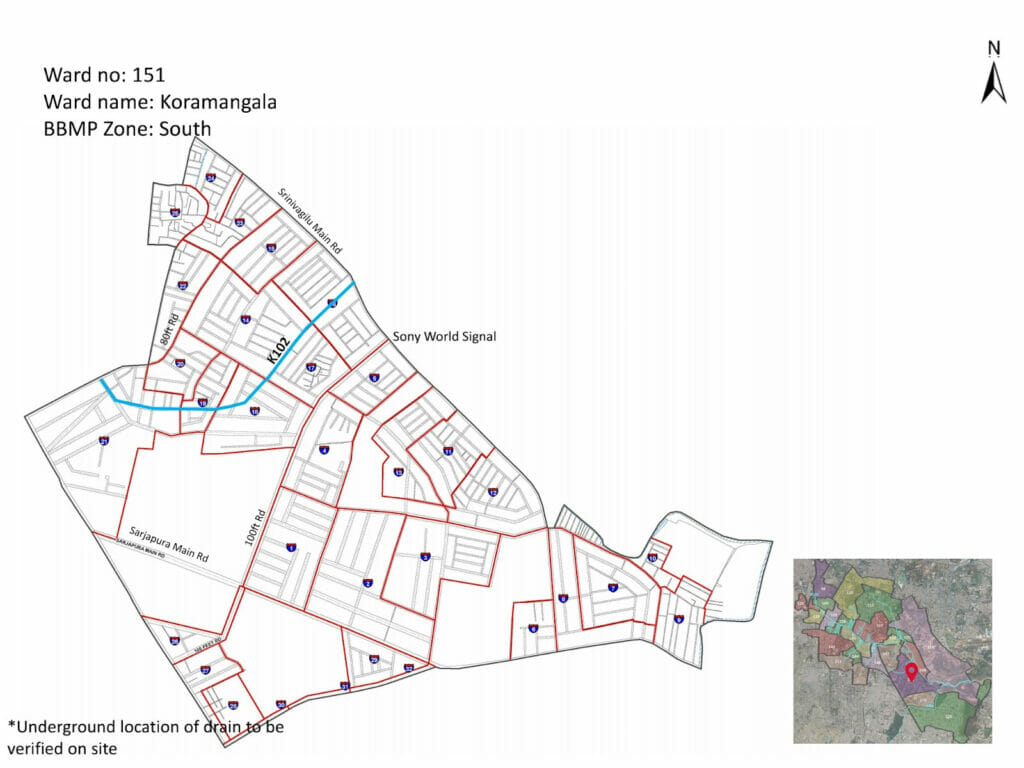

The drain then emerges next to the Croma showroom, near Sony World Junction, as it then makes its way towards Koramangala near the Wipro Park. Before it reaches Wipro Park, K-102 intersects the K-100 drain.

The way towards the Bellandur Lake

From Maharaja Signal, as you enter into the area, where the Prestige Park is visible, and you turn towards the road, where the D’Mart Shopping centre is, you come across a lone building facing the drain, which then leads to open land where you find the drain meandering towards Bellandur lake. It was at the sight my colleague Harsha, mentioned, “Why do we only have lake view apartments, why can’t we have Drain View Apartments?”. This was a poignant question, as it makes one wonder, how much do we really care about our cities?

Jacques Yonnet, a journalist who chronicled the street life in occupied Paris during World War II, had said, “To get to the heart of the city, to learn its most subtle secrets, takes infinite tenderness, and patience and sometimes to the point of despair. It calls for an artlessly delicate touch, a more or less unconditional love”. And I think, for both of us – Harsha and me – who travelled the stretch from Majestic to Bellandur, the drains and the areas that it crisscrosses left a deep impression. As you reach the final destination, I recollect the 2019 movie by Sindhu Thirumalaiswamy, The Lake and The Lake, that poses an important question, what constitutes a ‘nature’ worth protecting?

The secondary / tertiary drain connections

K-11O, another secondary drain, starts at Lalbagh road, past Mantri Blossom, Vinobha Nagar, and flows adjacent to Cement Colony and joins at Sudhamanagar in Ward 118. The secondary drains that start in Ward 143 consists of the following areas: Chikkanna Garden, Parvathipura, Mavalli, Upparahalli, Lalbagh Botanical Garden, Visweshwarapuram, Lalbagh kere (lake). Incidentally, media reports say Mantri Blossom is built on the storm water drain buffer zone.

K-109 that connects Sudhama Nagar drain is also referred to as Kanteerava Stadium drain starts, from Ward 110- Sampangiramnagar, the SWD passes through Cubbon Park, and around Sampangirama Nagar, via RR Mohan Roy Road and joins Double Road. The Kanteerava Stadium was built in 1946, on the lake bed of the Sampige Tank and the Kanteerava Indoor Stadium was built in 1995.

The Sampangi tank was built in the 16th century by Kempe Gowda-I, and was earlier named Sampigambudi. Today, only a small portion of the tank is preserved, as the Karaga festival keeps its annual date with the tank. The first Gange Puje of the 11 day festival happens at the Karagada Kunte or Koti Bavi. Earlier, this was also referred to as Uppinaneerina Kunte because the water was salty and water entered through the kaluves.

K-114 is also known as the Karnataka Hockey Stadium drain at Akkithimanahalli, Langford Road, which passes via St. Michael’s Church to connect the K-100 after the BMTC Shantinagar Bus stop. The stadium came up after breaching the Akkithimanahalli Tank/ Mud Tank, done as part of a government malaria eradication programme in the 1980s. The area was once a rice field, and hence the name akki meaning rice in Kannada and halli meaning village, thimma is the name of the person after whom the area was named.

K -108 starts at Jayanagar 1st block towards Lakkasandra and joins K 100 before National Dairy Research Institute. Jayanagar 1st block was once Siddapura ake.

K-107: Indian Christian Cemetery drainK-104: Pukhraj Layout to Hosur Road.

K-104: Pukhraj Layout to Hosur Road.

K-103: The secondary drain K-103, that starts at Church Street and connects Austin Town to Viveknagar joins to K-100 at this Y junction.

K-113: The secondary drain cuts though GST Office from Rajendra Nagar slum, joining behind NGV to connect to K-100.

K-102 Runs from behind the Forum Mall towards JNC road parallel to Raheja Arcade near the High Tension Wire. The Empire Hotel is part of catchment and joins the K-100 bridge near the Maharaja Signal.

The author wishes to credit Shreyas from Star Infratech, the firm implementing the K-100 project, Naresh Narasimhan, Amritha Ganapathy, Raghu from MOD foundation, Jayasimha from BBMP for the detailed explanation, on the secondary drains. In addition special acknowledgement to Malini Ranganathan, Meera Iyer, Rohini Malur, Bhargavi Rao, Leo Saldhana, Ram Prasad, Ammu Joseph, Amanda Gann, Harsha, Hita Unnikrishnan, Simmy Ganeriwala , Meera K, for their critical inputs and Beula Anthony and Shakunthala and Ramakanth, for accompanying me for the interviews.

This article is part of a series ‘As the drain goes’, a joint project by Pinky Chandran, Nalini Shekar, and Citizen Matters, and is supported by the Bengaluru Sustainability Forum (BSF).

[Part 4 in this series explored why there is a need to reimagine the city’s stormwater drains]

Entire Article is really informative. Having said that immediate attention needs to be given to #

https://twitter.com/rajbhagatt/status/1408787684739276802?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw%7Ctwcamp%5Etweetembed%7Ctwterm%5E1408787684739276802%7Ctwgr%5Ee0d410cb4503a0de8bfde6b406897efb01d3f68c%7Ctwcon%5Es1_&ref_url=https%3A%2F%2Fbengaluru.citizenmatters.in%2Fthe-k-100-drain-tour-109997

We Should tag – CM Twitter Handle | PMO Twitter Handle and All Lake conservation teams who work everyday on such matters.

Once it trends, immediate attention would start coming … thats my belief.