I couldn’t sleep. I followed most news channels and am part of several WhatsApp groups, none of which has anything to do with politics; yet all were a flurry of news — real or fake. Family members on the ground were less sure of what was happening, while those in the diaspora were supplying the information. It was surreal.

President Robert Mugabe, who had been in power for 37 years, was under house arrest. The military said they had taken over the country but it was not a coup. While the uncertainty was unsettling, there was reason to hope.

I was born and raised in Zimbabwe, which gained its independence in 1980 after more than a decade of civil war. I grew up in the 1990s euphoria of a newly free country where former Rhodesian companies, schools and houses were taken over by black Zimbabweans. The history of my country loomed over me, but I had a good childhood. Zimbabwe became known as the “breadbasket of Africa.” We exported maize and tobacco, among other goods. Our education remained British-centered. Our school desks still had 1950s-era ink bottle holes. With one foot we were marching to a future of success while the other firmly held to the past colonial influence and tribal tensions.

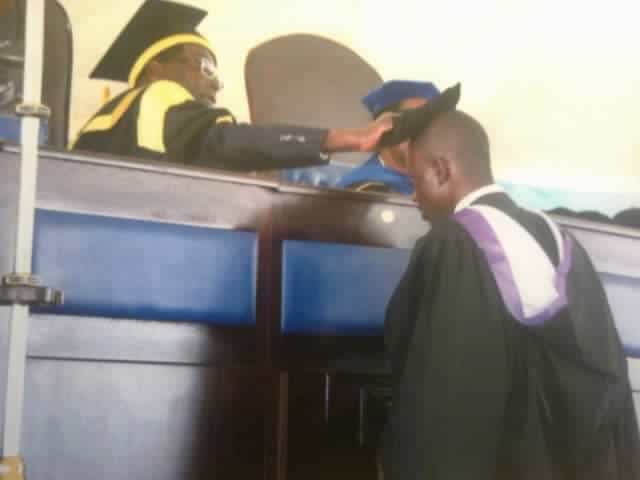

My graduation photo in 2014 in Zimbabwe.

In this seemingly idyllic life for which Zimbabweans had fought and died, cracks emerged. There was still the question of how to silence the opposition party, Zimbabwe African People’s Union, which was mainly populated by the minority Ndebele tribe. (The main party, Zimbabwe African National Union, was made up of mostly the majority Shona tribe.) In history I read that from 1983 to 1987, through a series of military actions called Gukurahundi, tens of thousands of Ndebeles were killed in the region of Matabeleland.From oral history I understand that in the capital, Harare, lives stayed the same —my aunt and uncle moved from the Matabeleland capital, Bulawayo, to Harare because of the unrest. I was not born yet to know the details. I was told Mr. Mugabe was popular at home and abroad, so they ignored them. Joshua Nkomo, ZAPU’s leader, escaped the country for a time. In 1987, an agreement was signed between the two parties and Mr. Nkomo became vice president.

There were a few scandals in the 1990s involving ministers stealing money in a car scheme. A minister was said to have committed suicide over it, while others resigned. Our lives continued in a flourishing Zimbabwe. In 1991, the World Bank started the Economic Structural Adjustment Program, which led to the devaluation of the Zimbabwean dollar. The creeping change was upon us.

Discontent led to protests and eventually farm invasions. White farmers and the young fled the country en masse, resulting in barren land and a missing generation. Most left Zimbabwe after high school for work or education, dismayed by the lack of job prospects in a nation that had the highest literacy rate in Africa.

In 2008, the opposition leader Morgan Tsvangirai won the presidential election but was forced into a power-sharing agreement with Mr. Mugabe. We had no food on the shop shelves except for salt packages. The Zimbabwean dollar was further devalued and worthless. Relatives flew into Harare with my bags full of groceries, which included toilet tissue and cooking oil. They would send money (a combination of black-market-bought American dollars and South African rands) for groceries with relatives and friends who were driving to neighbouring South Africa, Mozambique and Botswana.

Amid this drama, I was waiting to complete my studies. I was eager to relocate to a new country. Before that could happen, I had to survive in a tough environment. One school term I was quoted a price in the billions for tuition fees, which I was told I would have to pay within 48 hours. I returned after a week and the fee had doubled and was now in the trillions.

In the final three months of 2008 lost a lot of weight, mostly from worry and a limited diet. I worried about Zimbabwe, my family and our futures. I fell back in love with Zimbabwe. Despite its flaws, it was home. Despite holding billions and trillions of the devalued Zimbabwean dollars in my hands, I was hopeful that things would change.

When the power-sharing agreement was signed between ZANU and the opposition Movement for Democratic Change, food started reappearing on the shelves and we reverted to the American dollar and the South African rand as the official currencies. We hoped again. I saw a future where I would return home to live.

In 2017, people are celebrating the downfall of a near dynasty. I sit thousands of miles away still glued to social media and WhatsApp celebrating with my compatriots. Some, like me, have known no other leader besides Mr. Mugabe.

I have seen my country at its highest and its lowest points. We have yet to see what this new day brings, but we are ready for change.

To quote Lenin who once said: “There are decades where nothing happens; and there are weeks where decades happen.”