A once iconic bird in Bengaluru’s lakes is now a rare sight. Spot-billed pelicans, which are fish-eating water birds, were common, especially in large lakes across the city. Huge flocks of over a hundred birds would occupy lakes like Madiwala, Hebbal and Jakkur. But today, birdwatchers celebrate even sighting a handful of these birds.

The decline in the city is linked closely to mass deaths of the species in their breeding sites in the Mysuru-Mandya region. But the exact reason is a mystery.

Spot-billed pelicans or Pelicanus phillippensis are one of eight species of pelicans in the world and are found primarily in Peninsular India and Southeast Asia. These are large birds, with a nearly 2.5 metre wingspan, but their most recognisable feature is their throat pouches.

These pouches help the birds catch and swallow large fish. The species depends on freshwater wetlands and large trees for nesting colonies. And lakes in Bengaluru gave them plenty of both in the nineties, according to Subramanya S, ornithologist and retired agricultural scientist based in the city.

Pelicans: A timeline

When Subramanya talks about pelicans, there is an urgency in his voice. He sounds nearly frantic as he sets out a timeline of the species in the city. In the 1980s, when Subramanya was a scientist at the University of Agricultural Sciences, on the GKVK campus, he recalls pelicans being a rare sight. In fact, the Bengaluru Birdwatchers’ Club (of which Subramanya was a member) recorded just four sightings or encounters of pelicans in the Nelligudde Kere near Bidadi in 1986.

Things changed in the 1990s and early 2000s with the introduction of commercial fishing, notes Subramanya. The erstwhile Lake Development Authority started stocking commercial (and often exotic) species like Tilapia or African catfish.

Within a few years, fish-eating birds, especially pelicans, started thriving in these lakes. Commercial fishing brought in huge fish stocks to large lakes in the city leading to a boom in pelican numbers. In 2007, 240 pelicans in were recorded in Madiwala lake and 280 in Hebbal.

Read more: Pelicans seen in plenty

This was the case not just in Bengaluru. In January 2003, Subramanya recalls that the famous Kokkarebellur Bird Sanctuary in Mandya, an important breeding site for the species, had a record 700 individuals. The situation was similar in neighbouring Andhra Pradesh. “South India was a stronghold.”

Then the deaths started.

Parasitic infection

In 2015, four sick pelicans were rescued from Jakkur lake and treated at the Avian and Reptile Rehabilitation Centre (ARRC) located in Horamavu. The birds were found to have a nematode or roundworm infestation. Two of them died and two others were successfully treated. The incident has gone largely unnoticed, but Subramanya believes this is when it started.

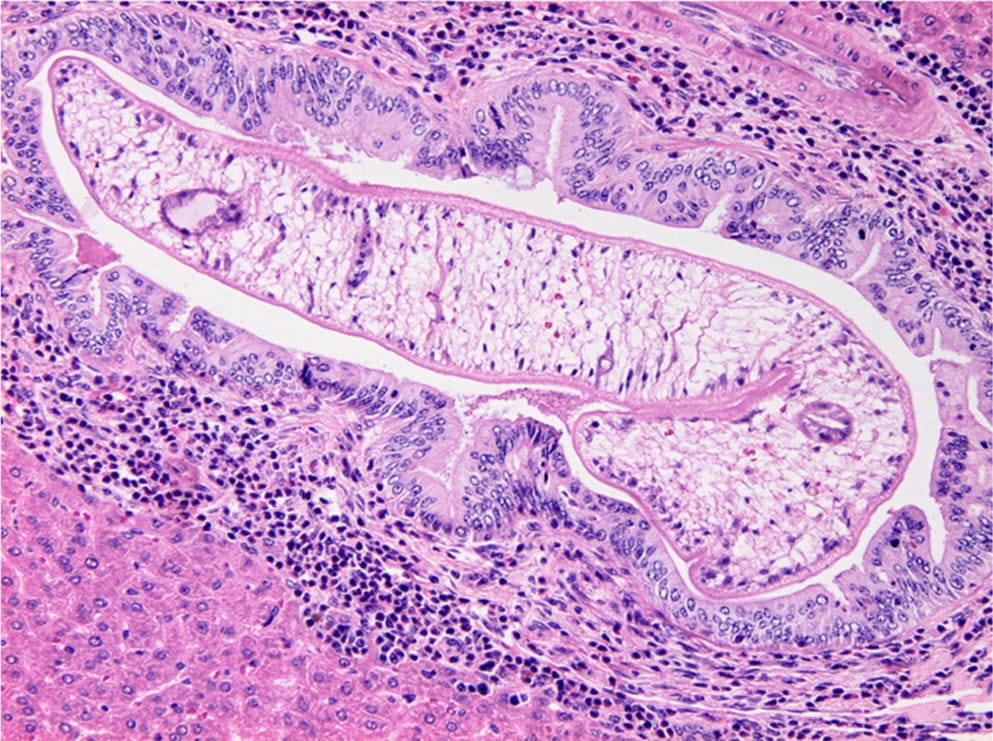

In 2017, 59 birds died in Kokkarebellur. Over 100 birds died in the subsequent years in waterbodies in the region. A postmortem, authorised by the Karnataka Forest Department in 2019, showed that the digestive organs of the birds were filled with three different gastrointestinal parasites. Contracaecum, a type of round worm, and Echinostoma sp. and Opisthorchis viverrini,, two types of flat worms.

Every aspect of pelican ecology appears to aid these gastrointestinal parasites. The worms attach themselves to small crustaceans in wetlands at the larval stage. These crustaceans are consumed by fish. The larvae develop further in the stomachs of fish, which are finally consumed by the pelicans. In the stomachs of pelicans, the larvae develop into adult worms and reproduce. The birds shed these eggs into the water along with their faeces, and the cycle continues.

Infestation spreading

Such parasitic infections are not uncommon in birds, fish, dogs or even humans. The problem comes when it leads to deaths, especially on a large scale. Kokkarebellur hasn’t seen any deaths this year. Forest department veterinarians have also been able to successfully recover a few infected pelicans, but Subramanya fears the infestation is spreading.

In 2020, birdwatchers recorded at least two dead and three sick pelicans at a lake in Chikkaballapur, not very far from North Bengaluru. Dead birds have also been recorded in other lakes in Mysuru and Mandya. Over a 150 pelicans died in Andhra Pradesh in 2022.

As a result, the species is collapsing in the country. Pelicans were listed globally as ‘Near Threatened’ by the International Union for Conservation of Nature. The early 2000s boom in South India had a lot to do with the status. But the 2023 State of India’s Birds report shows that spot-billed pelicans are rapidly declining, and the abundance is now lower than pre-2000 level.

Read more: A to Z guide to Bengaluru’s lakes

Unanswered questions

But what is causing this scale of infestation? The question remains unanswered. The 2019 study of the Kokkarebellur Pelicans revealed that apart from the dead birds, faecal samples of live birds, fish and water in nine lakes in the region were full of eggs and larvae of the parasites. However, the study could not say if there was any environmental factor leading to the scale of infestation.

Aksheetha Mahapatra, a researcher with the Karnataka Forest Department and a doctoral student at the Wildlife Institute of India, is in Kokkarebellur is hoping to solve this mystery. She says the department is now focused on identifying the root cause. “We are collecting water samples from different wetlands. We are identifying the lakes that pelicans use in the landscape and that should lead to better information.”

While the root cause has not yet been identified, many of the lakes in the region are polluted because of sugarcane factories and agricultural effluents. The researcher believes that there needs to be a study to see if effluents are linked to an increase in nematode infestation. Studies in other parts of the world have found linkages between water pollution and increased parasitic load in wetlands. For instance, a study in the US found an increase in flatworm infection in frogs living in ponds with increased pollution.

Vigilance from citizens

Bengaluru should be concerned because pelicans move through the landscape frequently. Two geo-tagged individuals from Kokkarebellur were found to be primarily moving through the Bengaluru-Mysuru landscape, explains Aksheetha. “The distance is nothing for the birds,” she says.

Meanwhile, Subramanya believes that Bengaluru’s lakes need to be monitored. Pelicans, he feels, are just the beginning. The ornithologist worries that the parasites might adapt to other fish-eating birds like Grey Herons, Painted Storks and Cormorants. In fact, Subramanya recalls 70-80 Great Cormorants, dying en masse at Kasavanahalli lake in 2018. The cause was never determined, but Subramanya continues to worry about that incident. “If these nematodes [worms] crack the code for other fish-eating species, it will be devastating,” he says.

Thus, while the hunt is on for the root cause, Subramanya wants more vigilance from birdwatchers and other citizens in Bengaluru. “Death matters a lot in this case. We need to record and report every fish-eating bird’s death, especially pelicans,” he says.

Subramanya hopes that birdwatchers in particular will note the presence of sick or dead birds on the citizen science platform eBird, and other citizens would report birds to the Forest Department. He also hopes that researchers will undertake a study of Bengaluru’s lakes to see how rampant the infestation is in these waters.

How you can help

If you spot a dead spot-billed pelican or any other fish-eating bird, share images along with the location details with us at bengaluru@citizenmatters.in or on our social media handles on Instagram, Threads and X (Twitter). If you find sick, but live birds you can WhatsApp the details to the Avian and Reptile Rehabilitation Centre at +919449642222.