In the mid 70s, when the Maharashtra Slum Area (Improvement, Clearance and Redevelopment) Act, 1971, was enforced in Bombay, Shabbir Qureshi, 60, witnessed a quiet evolution of his Wadala neighbourhood. His parents had immigrated from Gujarat and settled in the “jungle-like” village, from where they could observe the slow shaving of a nearby hill. All around, Qureshi remembers, were jhuggi jhopdis balanced with wood and bamboo. There were no community water taps or public toilets.

The new Act mandated that the government provide sanitary and hygienic conditions in slums. It called those with a “photo-pass” (government-issued identification cards) “protected occupiers” who “could construct or reconstruct a dwelling structure” subject to “terms and conditions”.

Qureshi’s family were protected occupiers. They were allowed to build a one metre wall on their 140-square foot plot and use a patra or a roofing sheet. Bit by bit, the gully’s kuccha houses received water and electricity connections. Cheap, recyclable materials were replaced with cement, and makeshift housing become one or two floors of pucca homes. The upgrade was not cheap. Qureshi’s father and older brothers coughed up Rs 35,000 in the year 1980—a formidable amount that was repaid for generations.

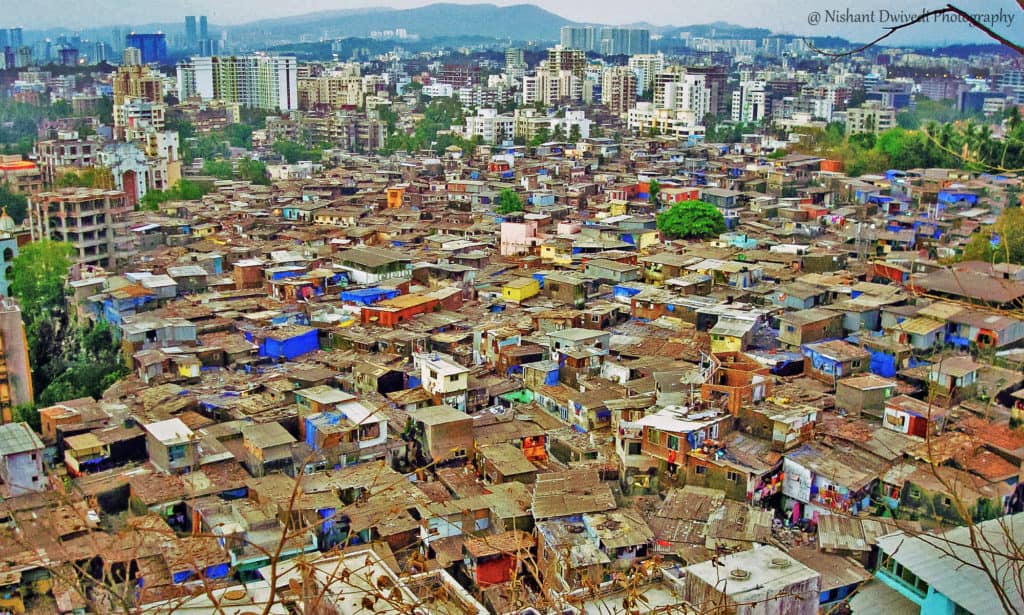

Across Mumbai, this is how residents of notified slums or bastis have built their homes—bit by bit, incrementally.

Many activists and non-profits have tried to galvanise support for this unhurried form of housing that doesn’t pinch government coffers, only demands no-eviction guarantees or land titles.

Governments needed to provide basic amenities, improve infrastructure, and offer the required technical and financial assistance to accelerate self-development, but the state imagination has largely been limited to builder-led redevelopment or resettlement.

Building your own home

“The SRA Act (Slum Rehabilitation Authority Act, 1995) allows communities to come together as a cooperative society and appoint their own lawyer or contractor,” says urban development practitioner Rohit Lahoti. Societies that carry out self-redevelopment are also granted 10% additional Floor Space Index (FSI) along with the permissible FSI, as per the Development Control Rules. “Why should a developer conduct redevelopment when the communities can do it?” Lahoti tells Citizen Matters.

In July 2020, Lahoti and Sayali Marawar were among the winners of The Nudge—Centre for Social Innovation’s Equal Cities challenge for their idea of a Do-It-Yourself toolkit to provide technical and ecosystem support to communities like Shabbir’s for self-development. But the self-development imagined here transcends scraping together a single housing unit, instead it is about mobilising communities to self redevelop.

Satish Lokhande, Chief Executive Officer, Slum Redevelopment Authority acknowledges that the slum Act allows people to form societies and pursue self-redevelopment. But “the societies can’t afford to redevelop themselves,” he says, “so they appoint a developer.” When pointed out that the regulations are in the favour of large builders, Lokhande says that SRA is “studying all options” for slum development. “Whatever options can develop the slums, we are examining.”

Hurdles to self-development

Few communities have managed to redevelop without large builders. “The nexus between politicians-builders-bureaucracy is so strong that despite the laws being in place, they keep the slum dwellers away from their legitimate rights,” Chandrashekhar Prabhu, a housing rights activist, says.

Plenty of challenges persist. First, there’s lack of awareness about the right to self-build. This is exacerbated by a range of formalities and processes earmarked by SRA that contort redevelopment in favour of large builders. FSI is also tradable commodity in Mumbai that makes a sizeable income for the municipal corporation.

Then there are financial constraints. Builders have access to a variety of loans and debt instruments but few borrowing opportunities are available for informal workers without salary slips or collateral.

Slums are not of recent origin in Mumbai. The Municipal Corporation was tasked with rehabilitating slum dwellers as far back as in 1933. Communities have historically negotiated with politicians and bureaucrats to remain on a piece of land, all while assessing security to incrementally build their homes. But slums have been thought of as a blight on the city. Instead of investing in in-situ development or development on site, governments have tried to raze them and resettle a fraction of residents in buildings on the city’s periphery.

The Maharashtra government has repeatedly promised to engage builders to house low-income residents through incentives like additional FSI and Transfer of Development Rights (TDR), where developers can purchase the development rights of certain parcels and transfer it to another.

But these interventions have repeatedly failed. When the Sena-led Maharashtra government promised to build 40 lakh new homes in 1995, architect Shirish B Patel wrote,”A few free lunches there may be, but nowhere near 40 lakhs.” He was correct.

“Today, if you take all the housing programmes from the Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission (JNNURM) to the Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana (PMAY) they haven’t produced housing stock for more than 5% (of the low-income class population),” says Sheela Patel, Director, The Society for the Promotion of Area Resource Centers (SPARC). Since 1986, SPARC has been at the forefront in fighting for housing and infrastructure rights for the urban poor in Mumbai.

Despite grandiose political promises, only about 2 lakh public housing units have been added to the housing stock, whereas Mumbai needs at least 11.36 lakh houses as of today, according to an affordable housing report by the Praja Foundation.

“If you want to make an investment in transforming people’s housing, it would constitute 3-4% of the country’s annual budget,” Patel says. An implausible and unscalable strategy, according to Patel, it also wilfully ignores that people have been building their own homes—little by little, everyday. It’s this self-building that needs to be scaled up.

In the late 1970s, World Bank supported a “sites and services” project in Mumbai’s Charkop area where low-income families could hold on to their plots of land and build it incrementally as their income grew. Initially, the scheme was termed as a failure because of the lack of immediate improvement. But thirty years later, the neighbourhood is found to be bustling. Families have invested to “add space, upgrade amenities, and improve construction materials, quality, and appearance,” a World Bank analysis finds.

But Mumbai’s affordable housing policy is no more about allocating spaces or supporting such incremental development. “If a majority of people are either building or renting houses like this, then should all of us try to substitute it with something else or deepen or strengthen this process?” asks Patel.