Bhubaneswar municipal corporation has been razing down dozens of land encroachments ahead of the Hockey World Cup to be held there in November 2018. About 250 families living in slums around Kalinga stadium where the world cup would be held are facing the threat of eviction. Municipal authorities are trying to use police support to do it, but the residents are insisting on proper rehabilitation before eviction. The land freed after all evictions will be used to create a land bank for development projects, say municipal authorities.

As per a recent report ‘Forced evictions in India in 2017’ by the Housing and Land Rights Network (HLRN), this is just one among the hundreds of slum demolition and eviction drives held across the country every year. The report says overall 213 settlements were evicted last year, by both state and central governments, in which 53,700 homes were demolished and 2.6 lakh people driven out, from urban and rural sums. This means that an average of six houses were demolished every hour. The evicted poor were left to fend for themselves, and were mostly not given any compensation or proper rehabilitation. When the poor are driven out of public land, no one keeps track of where they go and whether they survive.

The report says that the actual number of evictions could be much higher, since no official data is maintained on forced evictions, and the documented cases are only those known to HLRN. Forced eviction here means removing people from their home/land against their will, without giving them any legal or other protection. Such evictions are often done for trivial reasons such as getting higher rankings in Swachh Bharat Mission, or flyover beautification, and without following due process like giving prior notice.

Due process is laid down in laws, such as the Delhi Development Act 1957, and Slum Areas (Improvement and Clearance) Act 1956. In many cases, slum residents were evicted even when they had been living on the site for decades and had residence proof like voter ID and ration cards. The HLRN report says such forced evictions are contributing to rise in the numbers of homeless people.

Most evictions for ‘beautification’ and ‘development’

Of the evictions HLRN documented, the highest numbers (46%) were for ‘city beautification’, smart city projects, making cities slum-free, and for holding mega events. This includes Delhi government’s flyover beautification drive, wherein over 1500 homeless people living under flyovers were evicted.

The second biggest reason for eviction (25%) was building infrastructure and development projects like housing, metro, and widening of roads and canals. Some cases under this category are quite ironic, such as Indore Corporation’s eviction of 700 families in 2016 and 2017 just to meet Open Defecation Free (ODF) targets under SBM. As per an article in The Wire, cited in the HLRN report, Indore corporation had demolished these houses that didn’t have toilets, just before SBM surveyors came to assess the city. Indore then ended up in top spot in the SBM-2017 rankings, for meeting ODF and other targets.

Around 7000 houses were demolished last year for building new housing projects alone. This includes local authorities in Vadodara and Indore together demolishing over 4100 houses to implement PMAY (Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojna). In Hyderabad, 2800 houses were demolished for Telangana government’s ‘Two Bedroom Housing Programme’ for urban poor, without any guarantee of when the evicted people would get new houses.

Another 22% evictions were for forest/environment protection or disaster management. One such case was of 1000 tribal families evicted from Amchang Wildlife Sanctuary, based on a Gauhati High Court order. The families were displaced violently, with authorities using elephants to demolish homes, and injuring four people. These were families who had been previously displaced due to floods, and now displaced once again.

The report also points out that it is usually only the poor who get evicted for land encroachment, and that even judiciary has this bias. An example is of the Madras High Court ordering demolition of 60 tribal huts in Nilgiri district to protect the elephant corridor, even though tribals are protected from such displacement under the Forest Rights Act, 2006. The same court stayed the demolition of resorts in the area, saying that clarifications were needed on demarcating the area as an elephant corridor.

Another example is selective implementation of a 2015 Madras HC order to remove encroachments in Chennai and resettle those evicted. To implement the order, Tamil Nadu government removed over 4700 houses of urban poor, but not the commercial establishments that were encroaching. The evicted people were resettled 20-40 kms away, which affected their jobs and education. Worse, their resettlement sites were flood-prone.

HLRN report estimates that overall 17% of evictions last year were based on court orders. But the report also points to a few progressive court orders recently that upheld the right to housing, such as Supreme Court’s orders on rights of homeless people, and Delhi HC’s orders for rehabilitation in two cases of eviction.

Violence and deaths during evictions

In many cases, authorities neither gave notices in advance to residents before eviction nor allowed them to take away their belongings. For example, in Pul Mithai in Delhi, residents were never given a notice; bulldozers started razing their houses early one morning while they were still sleeping inside. Officials also confiscated dry fruits that the residents used to sell for livelihood.

In some cases, evictions have also led to deaths. For example, use of teargas shells during eviction contributed to the death of a two year-old boy in Kathputli Colony in Delhi. A 10-year-old boy who was evicted from a flyover in Delhi, who then lived on the roadside, died after being hit by a truck.

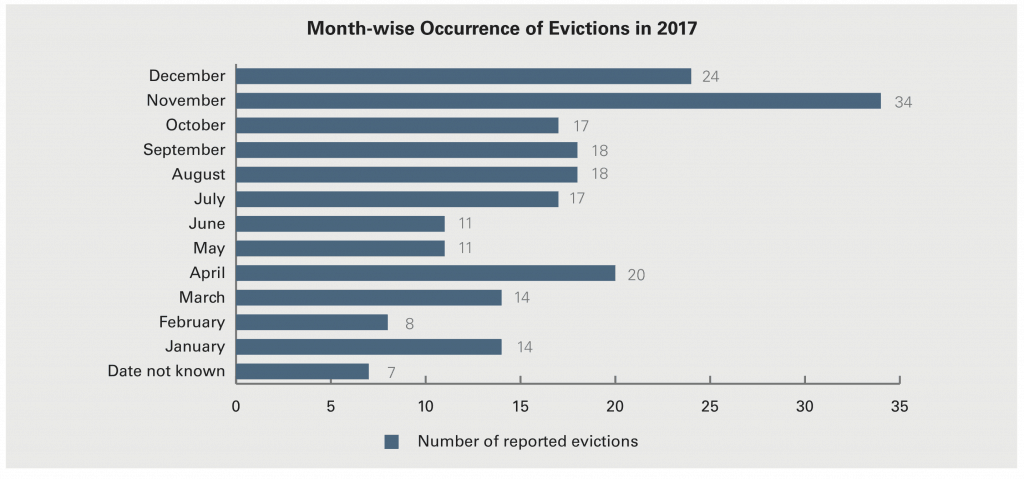

Many evictions are also held during extreme weather, compounding people’s suffering and threatening their survival. In Maharashtra, there is a government resolution prohibiting evictions during the monsoon, but last June, residents of Baltu Bai Nagar in Navi Mumbai were evicted during rains. HLRN data shows that the highest number of evictions were done in the winter months of November and December.

Many evictions were held just before annual school exams, preventing children from studying or appearing for exams. For many children, especially girls, this could mark the end of school education as they may become homeless or shift too far from school after eviction.

Resettlement lacking

Of those who are evicted, only a few get resettled, and that too inadequately. ‘Eligibility criteria’ becomes a convenient tool for authorities to avoid resettlement – residents who lack documents or were left out in government surveys are excluded, even if they had owned the house for long. For example, of the 1200 families who were evicted for Kolkata Book Fair, only 113 had become eligible for resettlement. Compensation is usually not given at all.

Even when resettlement is given, it would be in low-quality sites on city outskirts. In some cases, the outcome has been shocking – such as the case of slum residents resettled around factories in Mahul in Mumbai. Many of them have succumbed to deadly diseases that residents allege were caused by pollution.

Some governments also demand payment for the new houses, which the poor cannot afford. For eg., in Delhi, non-SC families need to pay an additional Rs 1.42 lakh for an alternative flat.

The report says these evictions violate the right to adequate housing, which has been recognised by some court judgements as an integral part of the Right to Life under Article 21 of the Constitution. They also violate India’s international treaty obligations. As per the report, another six lakh people in India may soon be evicted.

Evicted people become further impoverished, lose jobs, and often lack access to water and sanitation which affects their health. Women and girls become more vulnerable to sexual abuse and trafficking. The number of demolitions last year was higher than that in 2016. While the demolitions are being done rapidly, construction of new houses under PMAY is happening at a slow pace, says the report.

The report recommends that there should be informed consent of residents, and impact assessments done, before evictions. Those evicted should be given adequate resettlement and compensation, and considered for priority housing under Prime Minister Awas Yojana (PMAY). In general, the report says, government should invest more in low-cost housing while adopting ‘UN standards for adequate housing’ that assures security of tenure, basic services, adequate location etc. Without such basic provisions, urban ‘development’ would remain exclusionary and incomplete.