India is undergoing rapid urbanisation, the pace of which poses significant challenges to urban governance. India’s urban population has expanded from 26 percent of the total population in 1991, to 31 percent (or 400 million people) in 2011. It is estimated that by 2030, more than 40 percent of the Indian population will be living in cities. The question is: Are local urban governance structures in India equipped to respond to the needs of their citizens and tackle future problems?

Why is local government important?

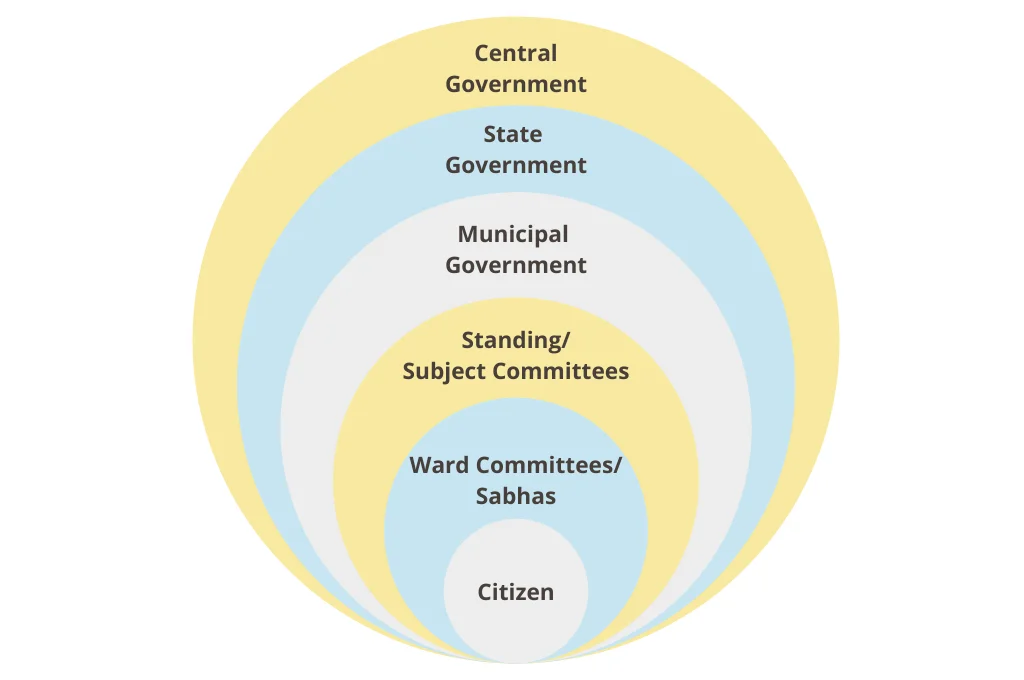

Local governments are the closest to understanding the problems and requirements of their citizens, and are therefore best equipped to make policies and decisions and implement projects. This is in line with the principle of subsidiarity, according to which the central authority should have a subsidiary function, performing only those tasks which cannot be performed efficiently at the local level by smaller bodies.

As seen in the case of the Swachh Bharat Mission, when city governments are the main agency involved in delivery of services, there is both innovation and effective delivery.

“When city governments are the main agency involved in delivery of services, there is both innovation and effective delivery.”

The decentralisation of India’s governance system gained momentum in 1992 with the 73rd and 74th Constitution amendment acts, which mandated the establishment of Panchayati Raj Institutions (PRIs) for rural areas and Urban Local Bodies (ULBs) for urban areas. The 74th amendment act devolves powers and functions to ULBs to enable them to act as local self-government and function as the third-tier of governments.

It has been more than 25 years since the passing of the act, but the actual devolution of powers and functions remains far from what was stipulated. State governments haven’t relinquished control, and the reasons for this range from the inherent challenges with change management, to questions of power and where decision-making control resides. With this in mind, it is essential to make sure that ULBs are seen as city governments and not merely as institutions for service delivery.

How can we empower city governments?

Empowering city governments requires addressing structural gaps in the existing urban governance framework and transferring funds, functions, and functionaries to the local-level.

In 2017, we at Praja launched a pan-India study to understand the implementation of the 74th amendment, challenges faced by city governments, and possible solutions. State-wise consultations were carried out across 21 states and the following areas of policy reform were identified to strengthen and empower city governments:

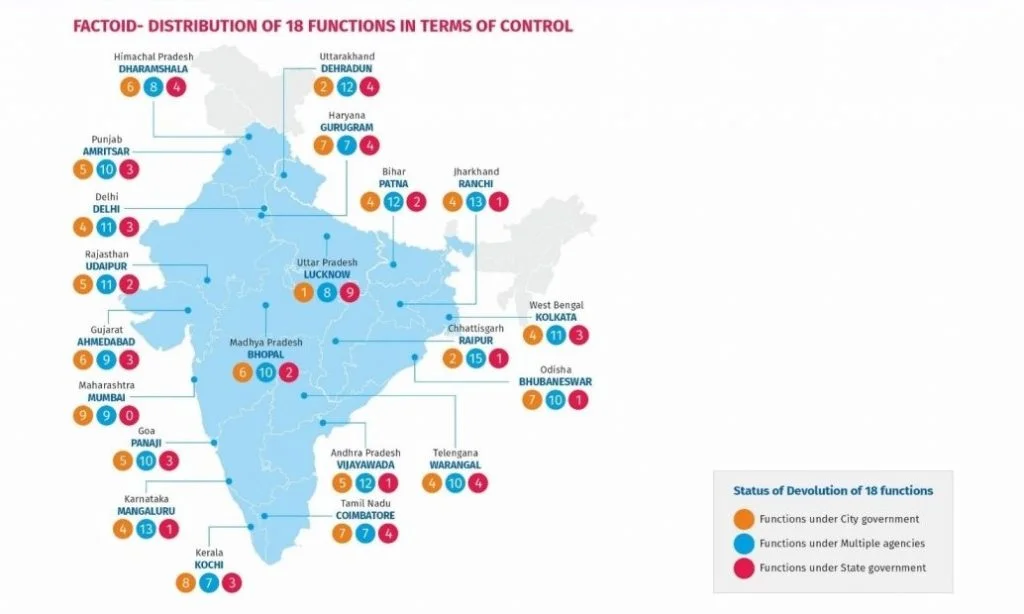

1. Devolving functions

The 74th amendment added the Twelfth Schedule to the Constitution, which outlines 18 functions that may be devolved to the city governments. However, the decision of which of the 18 functions to devolve was left to states, who could decide by enacting a municipal act. Our research shows that not even a single city of the 21 studied has control of all 18 functions. In nine cities, multiple agencies are involved in more than ten functions out of the 18, with no nodal agency to coordinate.

What needs to change? Even if implementation lies with other agencies, decision-making powers should lie only with the city government. The fact that city governments do not have complete control over the 18 functions leads to issues in delivery of services.

2. Building human resource capacity

To be able to deliver the functions efficiently and effectively, city governments also need human resources with adequate skills and capacities. The weak human resource capacity of city governments can be seen in the fact that not a single municipal corporation among the 21 cities has filled all available positions. To carry out the delivery of services, municipal corporations of Mumbai and Kolkata have eight employees per 1,000 population, while Gurugram and Patna have just one employee per 1,000 citizens.

What needs to change? The city government (rather than the state) should have the final authority to approve and conduct the recruitment process. Not a single municipal corporation has full control over the recruitment process. Although five of them can recruit people, the state government is the final sanctioning authority. Additionally, more states need to follow the example of Madhya Pradesh, Gujarat, and Tamil Nadu and create a specialised municipal official trained and experienced in municipal affairs such as a municipal cadre for effective administration.

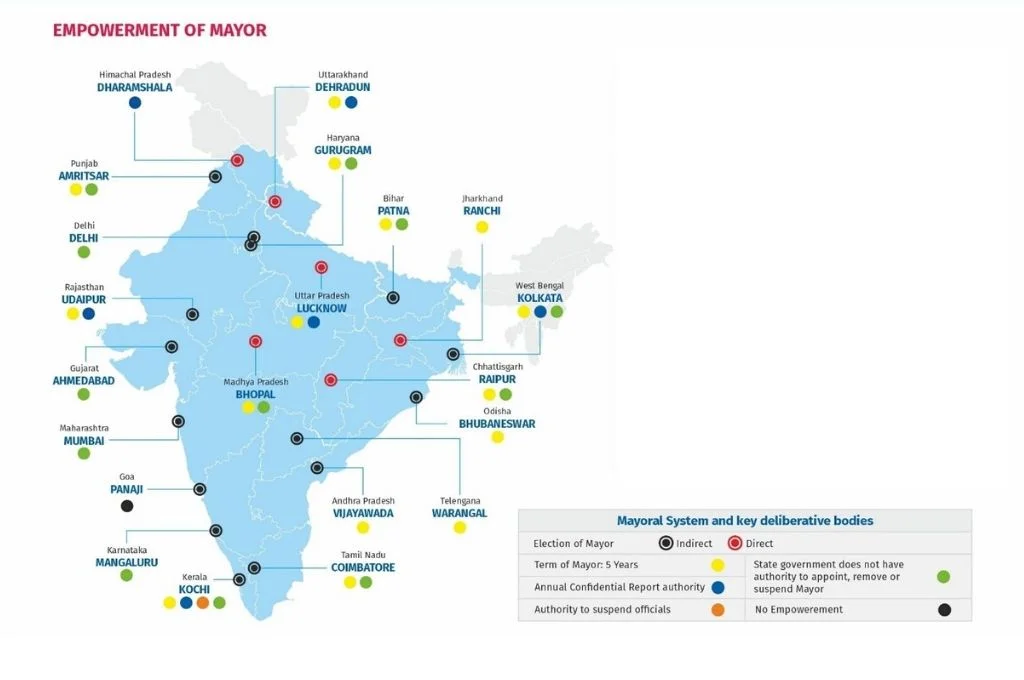

3. Empowering elected representatives and increasing accountability

As the head of the city government, the mayor needs to be empowered to ensure service delivery and accountability of the administration. After taking into account a number of parameters (such as the degree of administrative control given), it was found that mayors from Kerala are most empowered, followed by those from Rajasthan and West Bengal. On the other hand, in 16 of the states studied, mayors are only ceremonial heads, lacking administrative powers.

In addition to mayors, city councillors are also responsible for ensuring delivery of services and deliberate on the projects for decision-making for the city. Thus, they also need to be empowered by ensuring that each of them is a part of at least one deliberative committee and is being remunerated. In only six cities in the country, are councillors a part of at least one deliberative committee; in five cities, they do not get paid an honorarium.

What needs to change? To ensure accountability of these elected representatives, robust by-laws outlining the working of the corporation and procedure rules need to be enacted. Additionally, if the mayor and the councillors are not performing their duties, the councillors and the citizens of the ward respectively should have the authority to remove the person from their post.

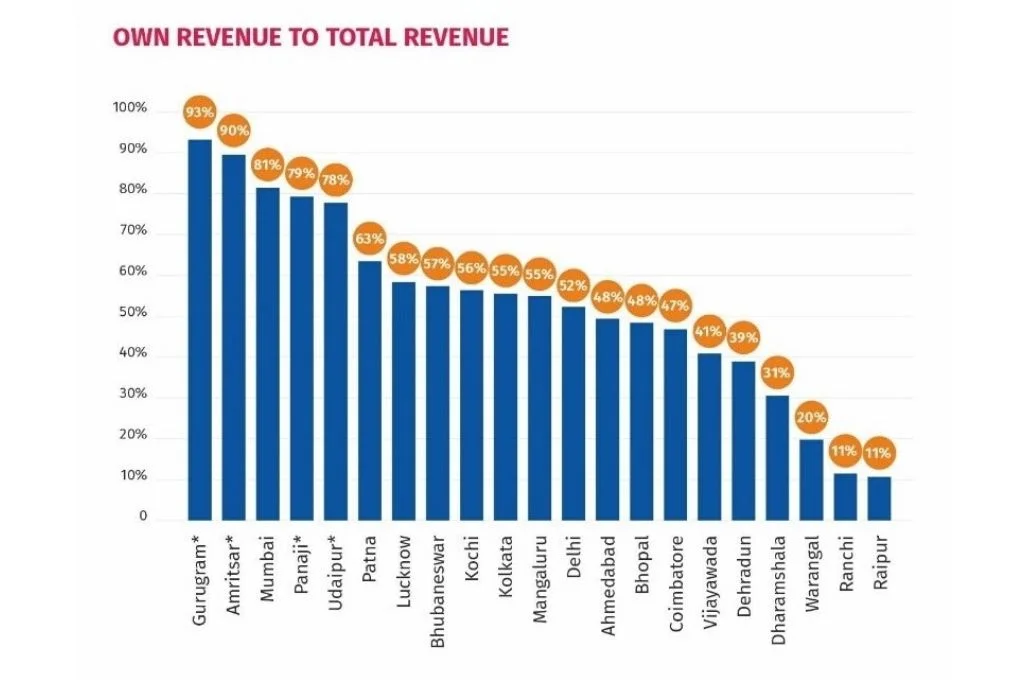

4. Making cities financially independent

Currently, city governments depend on the state and central governments for funds. For the city government to be independent and financially secure, fiscal decentralisation is very crucial. This involves transferring the power and authority to introduce new taxes and revise tax rates, among other things.

The Twelfth Schedule and Article 269 of the Constitution outline a list of taxes to be levied by the central and state governments. A separate list of taxes that city governments have full authority over needs to be created. No city across all 21 states has the power to introduce new taxes and only two city governments can revise tax rates.

What needs to change? To increase their revenue, city governments should expand coverage and increase efficiency in the collection of local taxes. In 11 cities out of 21, own-source revenue (revenue that cities raise themselves), constitutes less than 50 percent of total revenue. Property tax, in particular, is a major and important source of revenue for city governments, and should leveraged.

The power to make budgets also plays an important role in fiscal decentralisation. Approval for the city budget should not come from the state government. Out of the 21 states under study, city governments in only 11 states have the authority to approve the budget. Additionally, the financial sanctioning powers need to be decentralised to lower-level bodies. Mumbai is the only example of a city where sanctioning powers have been given to ward committees.

5. Ensuring active citizen participation

For transparency and accountability in the governance process, there needs to be active citizen participation, particularly in areas such as budget-making and urban planning.

What needs to change? To ensure this, municipal acts should have the provision for creating functional, decentralised platforms such as area sabhas and ward committees, which facilitate discussion and deliberation between elected representatives and citizens.

The municipal corporation acts of the states surveyed legally provide for the creation of ward committees. In practice, only eight have set up these ward committees, out of which only six are active.

There is a provision for area sabhas in the Municipal Corporation Act of only seven states. However, out of these, area sabhas are constituted and functional only in one city. Public participation does not take place at all in 15 out of the 21 cities.

6. Creating citizen grievance redressal mechanisms

In addition to area sabhas, ward councillors, committees, and councils, there should be a formal technology-enabled platform to register complaints, which will make city governments responsive to the needs of citizens. Only 16 city governments out of the 21 have a citizen complaint and grievance redressal mechanism.

What needs to change? The complaint redressal mechanism should be centralised for all the public services delivered in the city, irrespective of whether they’re delivered by a city, state, or central agency. It can then be directed to the concerned department. Through this mechanism, citizens should also be allowed to provide feedback and close complaints.

Addressing these structural and architectural problems of urban governance will ensure effective service delivery in cities, improving the quality of life for its citizens.

Know more:

- Dip in to Praja’s research carried out across two years and 21 states, to understand the challenges in the implementation of the 74th amendment.

- Listen to ‘The Seen and the Unseen’ podcasts, which discuss the importance of cities, the state of urban governance in India, and how urban governance can be reformed.

- Learn more about how urban governance and democratic local governance work in practice through PRIA’s Knowledge Resource Centre.

Do more:

- Praja is building a network of stakeholders across states. If you wish to be a part of the network, support the study, and/or receive regular updates about the study, write in to info@praja.org.

- If you’re a student who wishes to learn more about and work on urban governance issues, join the Praja Fellowship.

[This article was originally published on India Development Review and can be viewed here]