Not too far from 57-year-old Shivaji Sutar’s current rented room in Lower Parel is the Ganesh Nagar D slum, where one of Mumbai’s first slum self-development projects was initiated over 20 years ago.

Shivaji is among the 390 residents who pooled in money to upgrade his own hut and the basti into a residential complex with three seven-floor buildings.

All was going well. The first building was ready, a section of residents had moved in to flats in 2005, and the construction of the second building was proceeding. But in 2009-10, an alleged fraud wrapped the project in a terse and spiralling litigation and halted the construction.

110 residents like Shivaji were left homeless.

“I do not understand what happened,” Shivaji says. “The committee members keep blaming each other. Humara satyanash ho gaya.” Our lives are ruined.

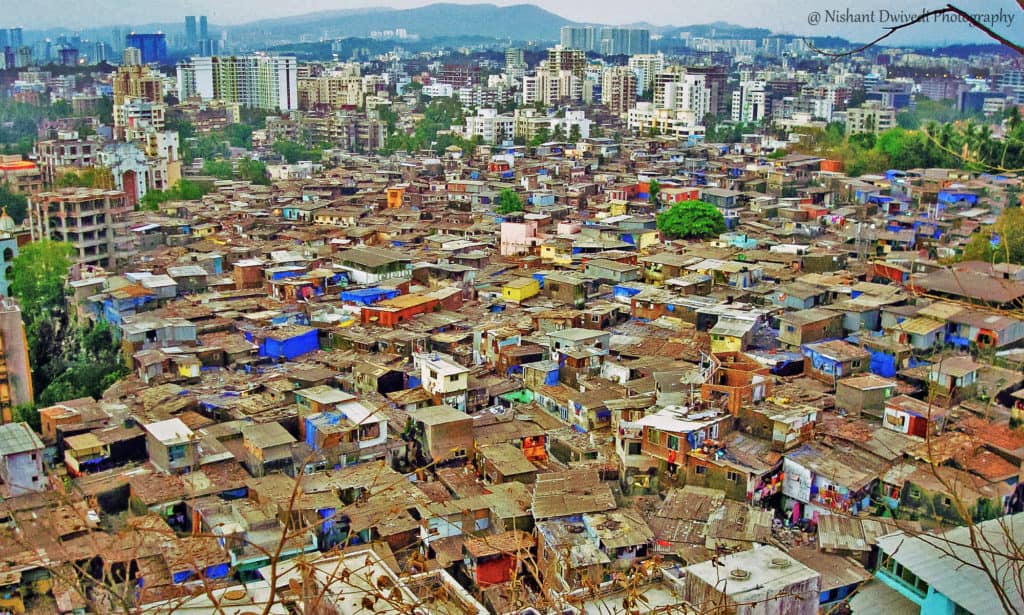

Self-development is often touted as a model for better urban housing. When people have a guaranteed right over land, access to basic amenities, and technical assistance, they build better housing for themselves. It is considered an antidote to builder-led redevelopment or resettlement. But financing and sustaining a large self-development project is a herculean task, susceptible to persistent disagreement and dispute.

The Ganesh Nagar D Example

In the early 2000s, 390 residents of the Ganesh Nagar D slum had elected a committee consisting of chairperson (late) Bharat Gayekar, secretary Sharad Mohite, treasurer Mallappa Korvi and other members. The residents proposed to pursue self-development of their slum with the help of a non-governmental organisation, Slum Rehabilitation Society (SRS). This meant they would self-finance the construction and appoint their own contractor, as opposed to handing over the reins to a developer.

The committee and SRS planned to fund the project through funds provided by SRS, resident contributions, a loan, and the sale of a few flats and Transferable Development Rights in tranches. But in 2009-10, the project was abruptly stopped when the chairperson and secretary were accused of an alleged fraud.

In the aftermath of the fraud, Shivaji tells Citizen Matters that the residents are divided into various “parties”. “Some support Mohite, some support Korvi. In all this resistance, we are affected. Every 11 months, I have to find a new room to rent,” he adds. Those who didn’t receive a flat have moved across the Mumbai Metropolitan Region (MMR), from Virar to Kalyan. They are enduring the city’s high rents, awaiting the day they would move into their flats.

Sakaram Kadam is another resident who hasn’t received a flat. He runs a laundry shop in the Ganesh Nagar D slum area and lives with his wife in the room on the first floor. Sakaram knows about the alleged fraud but the details are elusive – a response from most other residents. “The Slum Rehabilitation Authority (SRA) is investigating,” he says. “We will know when the inquiry is over.”

In 2014, SRA appointed P. K. Sanakke as an administrator for the Ganesh Nagar D slum committee. “There was a mismatch in accounts,” Sanakke says. “Hisaab-kitaab nahi mil raha tha. The former committee has not made their accounts available.” Residents like Sakaram and Shivaji have heard about the incomplete paperwork. “Some said the NGO SRS was handling the documentation, some said the committee was,” Shivaji says.

SRS tells Citizen Matters that they maintained the accounts of the project until 2004-05 “when the last audited report was published by the Ganesh Nagar ‘D’ (GND) Committee as part of that year’s Annual Report”. “The originals of all financial records, after approvals and processing, were sent to and kept on file by the GND Committee. SRS which had maintained photocopies of these documents has previously turned over an entire set to SRA to enable scrutiny and audit, for which the latter has acknowledged receipt,” Yorick Fonseca, Secretary & Director, SRS, says.

New Committee Appointed

The investigation remained incomplete in Sanakke’s tenure but the residents tried to resume the project. Elections were held in late-2015 to setup a new committee with Sattappa Patil as the chairperson and Priyanka Kokate as the secretary.

“We got incomplete paperwork from the previous committee,” Priyanka Kokate maintains. But the new committee tried to make their appointment successful by focussing on the incomplete, unserviced second building. The slum committee did not receive an Occupancy Certificate for the second building and services like drainage, water connection or electricity were not available, so residents were prevented from moving in.

According to Priyanka, a lot of outsiders encroached the building. “We got everyone whose name was not on the list evicted and worked with the corporator and BMC to provide basic services such as an electricity and water connection.” Priyanka’s family also received a flat in the second building but they live with Priyanka’s brother in Lower Parel.

Khajansi Sahni, 57, a resident in the second building says they are still struggling. The 57-year-old has to climb five floors to reach his flat. There is a common tap on each floor that families use to store water, he says. “There’s no drainage so people use community toilets,” he adds. Services may be inadequate but at least they exist, Khajansi says. The patchwork of services has helped families like the Sahnis move into a flat in the second building.

But even the Patil-Priyanka Kokate committee wasn’t able to complete its full tenure of five years and was dissolved in 2019, the committee’s vice secretary Santoram Kalvikatte says. “On one side there were mounting court cases, on the other we had many internal differences. We were not able to do any work.” But Priyanka says that a few residents built pressure to dissolve the committee despite their effort to provide basic amenities and help people move into the second building.

Santoram says he took a step back from committee work even before it was dissolved. He had learnt that not all committee members were being kept in the loop about ongoing developments. “Other committee members would hold meetings and I wouldn’t be informed,” he says.

Most residents highlight this information asymmetry in the workings of the Ganesh Nagar D slum committees. A resident in the second building says that the committee members don’t tell the residents everything. “It’s only during big meetings that we find out what’s going on.” Those active in the committee complain that not all residents demonstrate initiative or interest.

In 2019, SRA appointed Devdas Aroskar as an administrator to continue the investigation, but a few residents led by Sunita Khamgaokar have challenged the appointment, according to Santoram. Aroskar says he hasn’t got charge of the project. “This happens when the committee doesn’t want an administrator to look at their affairs, and want to keep the control with themselves,” he says.

Sunita Khamgaokar denies the claim.

Breaking Away from Self-Development

Now, Ganesh Nagar D has found itself in a similar situation as it was almost 10 years ago when the fraud was alleged – without a functional committee. But the problem is only exacerbated by the ongoing litigation and dissension among the committee members. Fonseca from SRS says that they are committed to the project but are still “awaiting the results of ongoing investigations, the outcome of pending legal cases, the decision of the SRA authorities, the election of a properly elected and constituted new committee, and most importantly the conduct of a financial audit of the last 15 years”.

One commonality, however, cuts across committee members, residents and SRS. And that’s a desire that the 110 residents no longer have to rent rooms away from Ganesh Nagar D. Residents like Sakaram are most hopeful. “We have to move ahead,” he says, “and work together to complete the project.”

In 2016, the new committee asked residents if they wanted to pursue self-development or approach builders. “The majority opted for builder-led development,” Santoram says. Two years ago, Omkar builders showed interest, Shivaji Sutar remembers. Finally, he thought, their problems would end, but the builder didn’t proceed with the project.

The residents have approached a new builder yet again and hope that a builder would now complete what started as an ambitious self-development project.

We had written about the same self development project last month as well. This story attempts to take the arguments forward.