In an earlier article, we investigated the pervasive pattern of unfilled seats reserved under the Right to Education (RTE) Act. Here, we spend an evening at an RTE verification centre in suburban Mumbai, talking to parents and a member of the RTE verification committee about the admission process.

On the afternoon of May 27th, I met 3 mothers waiting in worry to secure admission for their children to different private schools. They were at the Gilbert Hill MNP Urdu School for the verification of their documents. This was no routine admission step; their children were among the select few that had been chosen for an all-expenses waived education from the 1st grade till the 8th under the Right to Education (RTE) Act.

Section 12(1)(c) of the Act mandates all private, unaided, non-minority schools reserve 25 per cent of their seats for children from poor and disadvantaged groups. In Maharashtra, this includes students with disabilities, from families with an annual income under Rs 1 lakh, scheduled castes (SC), scheduled tribes (ST) and religious minorities.

After a lengthy struggle, the mothers – Shaista, Afroz and Heena – were at the RTE verification centre for the culmination of the process. It was the last day to do so, and they had been left to stare at the empty hallway of the school since 3 pm.

Applications began in February. “Din din bahar baithna padta tha (We had to sit for days on end),” said Afroz, mother to 6-year-old Mohammed. She had gone to a camp organised by the local corporator in Jogeshwari to help in filling the forms – and she was not alone. Thousands of parents, mostly mothers, had joined. This was not an opportunity they could afford to lose.

The application process for the reserved seats under RTE

Applications for the seats reserved under RTE are entirely online. But this often poses an accessibility issue for parents from lower-income and socially disadvantaged houses. Making an online account, filling out the form and geotagging their exact location on an available internet device – most often a mobile phone – is far from easy. Parents require help to complete these formalities.

Increasingly, camps organised by local politicians, NGOs and social workers have become a popular means for registering applications. All the three parents with me had applied through camps in their neighbourhoods.

As these camps – sometimes even two laptops and a desk set up in a galli (street) of an informal settlement – have proliferated, awareness of the reserved seats has increased. The number of applicants has doubled in the last six years, going from 6,409 in 2016-17 to 15,143 in 2021-22. According to the Maharashtra government’s School Education and Sports Department website, 15,050 applied this year.

However, the number of seats has been reducing by the year, in part due to more schools applying for minority status. While almost 10,000 seats were up for grabs in 2016-17, only around 6,500 were available in 2021-22. 6,451 spots are available this year – not enough to accommodate even half the applicants. The lucky students are chosen first by a random lottery, and then off a waiting list.

It is at these stages cracks in the policy appear. Despite the large number of students contesting for the few seats, a large number of seats go unfilled every year. Selections do not always translate into admissions for the applicants.

Absentees, documentation issues and rejections by schools all contribute to the poor seat fill rate. This year, only 3,243 of the 5,342 selected applicants were able to confirm their admissions after being chosen in the lottery round. In the subsequent admission rounds off the waiting list, only 906 of the 2,083 selected applicants confirmed their admissions. 2,302 of the reserved seats in Mumbai are still vacant (as of July 7th).

Read more: Why do so many seats reserved under the Right To Education (RTE) Act go vacant?

At the RTE verification centre

The three parents waiting with me on May 27th were second time lucky – their children’s names appeared in the second round on May 19th, but then began another ticking race.

They had one week to submit all the documents to the RTE verification committee. Address proof, birth certificate and income certificate – which all the three mothers had scrambled to organise. It had taken them the whole week to arrange for it, even costing Afroz Rs 1,500.

“List me aa gaya hai to padhana to hai, private school hai to kyu nahi padaenge (Now that his name has come on the list, we definitely want the admission. It’s a private school, so why wouldn’t we?),” said Afroz.

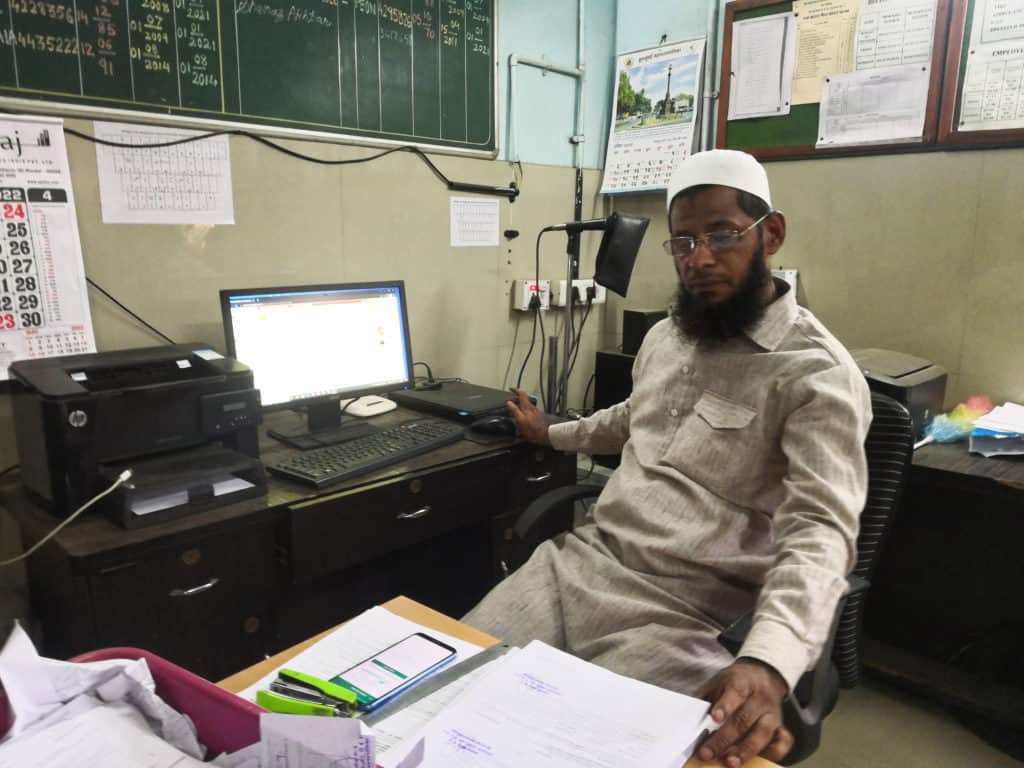

Aslam Shaikh, a member of the RTE verification committee is a crucial link at this point for these mothers. The mothers had been waiting for almost 2 hours since he’d left for lunch, bringing the looming deadline closer to the end. They would have to wait more, as he spoke first to me.

“Isme jyadatar aadmi aate nahi hai, sab aurate hi bhagte hai (Men aren’t the ones who come, it’s the women who run around),” said Aslam. There was no cause to worry, he assured us, as the admission from his end was almost a done deal.

As the parent’s representative in the 20-member committee and a social worker, this was another step where the lucky parents got help. If they didn’t have a particular document, Aslam suggested an alternative: a new bank account or gas cylinder connection for an address proof, an affidavit for age proof, etc. Following up with the parents, he made sure the parents used their opportunity to send their child to a private, hence considered good, school.

The future at stake

“Shuru mai first standard se hi bacha agar achi school me jae, to uska aage ka future acha jata hai (If a student gets in a good school right from the start, their future also has the chance to go right),” he told me.

This is a scenario my parents, like many of you reading this, never had to grapple with. My admissions were never hanging by a thread, with my future as collateral. I always had options when choosing schools and I could demand better from them, or switch. It’s hard to imagine the entire process being anything but terrifying. Without Aslam’s assurance and help, the parents would probably have to miss what seems like a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.

For 6-year-old Ishaaq, this has but one meaning. After a year of online school, he was excited to finally go to a school with a playground!