“”Kitne aadmi the?” The scene featuring Gabbar Singh’s famous question in Sholay has a rarely noticed sideshow. A small lizard scampering across the rocky terrain of Ramanagara, located just outside Bengaluru, where the iconic movie was filmed.

That lizard is the Peninsular Rock Agama, or Psammophilus dorsalis, which can be found today mainly in Bengaluru’s rocky outskirts. The city’s ever expanding urbanisation has not only altered natural landscapes in its wake, but also destroyed habitats of species like the Rock Agama lizard. And although not endangered, the Peninsular Rock Agama is no longer a common sight across the city as it once was.

In a study done in 2020 examining the effects of urbanisation on the lizard species, researchers at the Centre for Ecological Sciences at the Indian Institute of Science found significant changes to the Agama’s natural habitat.

Changing landscape

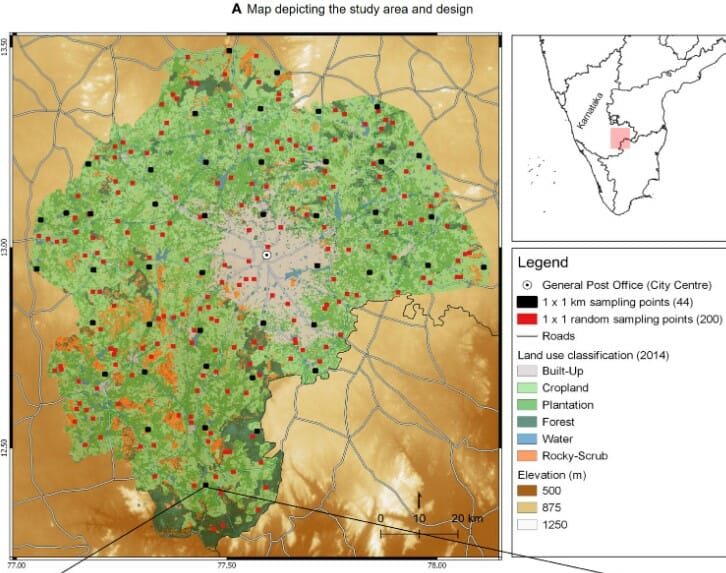

A micro-level analysis had revealed a 1028% increase in urban built up areas since 1978, causing an uptick in land surface temperatures. Considering the General Post Office as the centre of the city, the authors of the study, titled ‘An expanding cityscape and its multi-scale effects on lizard distribution‘, found that Bengaluru’s built-up area is concentrated within a 20km radius of the GPO.

Through satellite images spanning across Ramanagara on one end and Kolar on the other, they found that rocks and boulders had been converted into plantations and large swathes of built-up area had replaced agricultural lands since 2005-06.

The study described the changing landscapes using satellite data and attempted to explain why the Rock Agamas are found in some places but absent in others. “We considered the percentage of built-up area (buildings as a sign of an area being urbanised), as well as distance to the city centre and examined how environmental factors change,” says Seshadri K S, post-doctoral fellow at CES, IISc and one of the authors of the study.

As you move away from the city, the number of buildings decreases and this has a strong relationship with the presence of the lizard, the study finds. “Which means if you move radially outwards, you’re more likely to find a Rock Agama” says Seshadri. He mentions how this was also attributed to land surface temperatures (LST) as lizards are found in hotter areas.

Being ectotherms, lizards regulate their body temperature based on external sources/environment. And LST was lower in the city, getting hotter as one moved outwards. “Bangalore is unique in that despite lots of buildings, the presence of trees and the general topography appears to cool the land surface rather significantly,” explains Seshadri.

Dr Harish Prakash, a postdoctoral fellow and co-author of the study says that cooler surface area might also be because the city is at an elevation.

“The absence of rocks explains the absence of the Rock Agama, and because there is a higher proportion of rocks in the city outskirts, the lizards are more commonly found there” Seshadri added.

Artificial light at night (ALAN) was also a factor that influenced the lizard’s presence. The lizards have circadian rhythms, which means their bodies follow the 24-hour cycle. “Due to human activities, their sleep cycles might be disturbed because all places are lit up,” says Seshadri. “Additionally, these light sources might attract insects and they might end up foraging for longer”.

“As you move away from the city centre, artificial light at night decreases, meaning the nights are darker in the outskirts of the city than in the centre,” says Dr Harish when asked about habitats conducive for the lizard, which include relatively high LST and rocky and scrubby areas.

Read more: Unchecked tree loss is wiping out the Slender Loris from Bengaluru

Habitats, or the lack thereof

Both authors further emphasise the need for connectivity between two habitat landscapes for the lizard to thrive.

“In the outskirts, highways and other anthropogenic barriers cut through the rocky landscapes,” says Dr Harish. “This means that the lizard populations might get isolated and not move between habitats due to lack of connectivity”.

Echoing this, Seshadri maintains that habitat connectivity is necessary for dispersal. “In an area with 200 lizards, they would eventually become extinct if there is no habitat connectivity,” he explains. “Isolated populations can experience inbreeding depression and populations can decline because of it. These can be remediated if we establish connectivity between landscapes that still have habitats that can sustain lizards and their needs”.

The Rock Agamas could be seen in Lalbagh and Cubbon park two decades ago. “Even though Lalbagh has a geological rock formation, the habitat is surrounded by a sea of buildings,” says Seshadri, as the most likely reason for the disappearance of lizards from these places.

“Around Sahakarnagar or Gandhi Krishi Vigyana Kendra (GKVK), you can still find them on vacant plots or compound walls, so we know some part of urban constructions are useful for them,” he adds.

Extinction threat

Urban Bengaluru is not just altering habitats of species, but there are components of it that threaten the very existence of the Rock Agama. “Insects are the lizard’s food, but residents, especially around apartments, go with their fogging machines to kill them,” says Seshadri. “While this doesn’t kill the Rock Agama directly, lack of food sources will cause its population to slowly decline”.

Although he attests to their presence in places like Sahakarnagar, Seshadri doesn’t know how long they will continue to be around. “They bask on the roads because roads have higher surface temperatures and take longer to cool, but this also means they might end up as roadkill,” he points out.

Dr Harish also mentions how rampant mining happening in the city outskirts has to be curbed because these rocky landscapes are home to many species besides lizards. While residents might not directly be affected, species going missing might come to impact us in different ways. For instance, insectivorous creatures control the population of insect pests, emphasise both authors.

There is also a need for micro-habitat level data through periodic studies that will provide enough evidence about the lizard’s behavioural and habitat changes over the long run, the authors argue.

Seshadri says that people are yet to notice the absence of the Rock Agama. “When the sparrows were around, no one cared and now everyone’s noticing their absence. If we’re not careful, the same might happen with the Rock Agama”.