Mumbai, July 2005. Surat, August 2006. Chennai, December 2015.

All these cities have shown us the costs of disregarding and abusing our urban commons and wetlands, which used to be referred to in Taamizh language with respect, using a special term: Poromboke. The question is, are we willing to see and learn?

Every instance of heavy rainfall in a city reminds us what happens when our urban development authorities and administration ignore the rivers and wetlands in our cities. Rivers Remember: #ChennaiRains and the Shocking Truth of a Manmade Flood by Krupa Ge is one more stark pointer.

The book is an outcome of the author’s effort to understand what caused the flood in December 2015 in Chennai. Her book brings back memories of three rivers that traverse the city: Kosasthalaiyar, Adyar and Cooum. She also weaves in stories by listening to the tales of people living on the banks of the Buckingham Canal and in close vicinity of the lakes in Chennai city.

The book is an outcome of the author’s effort to understand what caused the flood in December 2015 in Chennai. Her book brings back memories of three rivers that traverse the city: Kosasthalaiyar, Adyar and Cooum. She also weaves in stories by listening to the tales of people living on the banks of the Buckingham Canal and in close vicinity of the lakes in Chennai city.

Between the lines

The book opens with a very personal account of how her parents’ home went under water on that fateful night of December 1st, 2015. By the time you move from the first story to the second story in the book, you realise that this author is going to work her way through the dual metaphor of ‘our home’ vs ‘their home’, wherein the latter stands for the claim of rivers and wetlands over the land on which their waters have flown.

This is not quick disaster reportage from ground – although even that genre of human interest reporting may have its own value – but a result of three years of persistent effort by an author to understand urban planning, administration and disaster preparedness in Chennai. She laments that “the ancient practice of kudimaramathu – kudi meaning people and maramathu meaning repair, wherein a village was responsible for maintaining, repairing and taking care of water bodies – died out over time.” (p. 18).

She also tells us about her own earnest efforts to become a water literate citizen, her own moment of learning and finding out about the waterbodies on which Chennai’s water supply depends and how urban expansion has undermined this very complex network of waterbodies and drainage system.

However, this book is not only about the question ‘What caused the flood?’ – even though that is a title of a chapter where she tells us of her efforts to find the answer to it by filing numerous RTIs and knocking several doors. It is also about the way fellow citizens came forward to organise the rescue and relief missions. Krupa goes to fishing hamlets and brings back with her stories about how the young boys from the fisherfolk community rushed in with their kattamarans and boats to lend a helping hand. If on one hand the book brings back the painful memories of avoidable casualties and deaths, it also gives us a glimpse of guardian angels such as those who relocated expectant mothers from Dr Bala Kumari’s nursing home.

The author also keeps transporting the reader back and forth over several centuries through her ability to weave in the narratives from earlier accounts on these rivers and quoting from memories shared. She acknowledges the debts that she owes to her sources every time she writes and at the end of the book you find the citations that runs into 105 endnotes!

She thus leads curious readers to historian Venkatesh Ramakrishnan, who is known for his work on the cartography of the river Cooum. When she talks about the Ennore creek and the toxic pollution caused by the North Chennai Thermal Power Station, she makes us acquainted with the wonderful activist Pooja Kumar of Coastal Resource Centre. She also talks about the work of Nityanand Jayraman of Vettiver Collective.

A notable coincidence

Interestingly, I got a first glimpse of this book not at a bookstore, but on the table of Vettiver Collective last June, when I was speaking to this activist scholar about the impacts of the State Industries Promotion Corporation of Tamil Nadu (SIPCOT). As we talked about the importance of auditing land acquisition and allotment practices in Tamil Nadu, I noticed the book and was curious to know what it talked about.

It instantly caught my attention; I have written extensively in the past about the performance audits carried out by CAG of India on flood control and management programmes, and in one article I also wondered, ‘When will our auditors learn from ecologists.’ I discovered that this book actually takes a deep interest in the Performance Audit by CAG of India on Chennai Floods.

Krupa Ge tells us about her efforts to trace the CAG report, whose tabling got delayed by almost a year. It was through her sustained efforts to use RTI application and appeals against the first reply, that she chanced upon 320 pages of correspondence between heads of different line departments replying to the performance audit and the then chief secretary of Tamil Nadu trying to obfuscate the auditors and delay the final report.

Readers who wish to really understand how brazenly our administrators could refuse or parry responding to the constitutional auditor, do look at the excerpt from this book here on The News Minute.

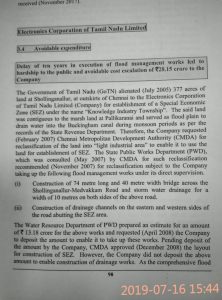

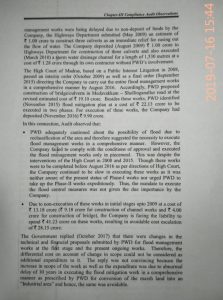

But more importantly, I think the pertinent question that arises from this book is how little do we learn from the frequent urban flood disasters. Lest we forget, here is a one-page excerpt from yet another CAG audit report that tells us how the Electronic Development Corporation of Tamil Nadu had delayed execution of flood mitigation works for 10 years.

Necessary reminders

In the final analysis, as the song by Kaber Vasuki, Chennai Poromboke Paadal sung by T. M. Krishna reminds us:

“It was not the rivers that chose to flow through cities

Rather, it was around rivers that the cities chose to grow”.

Whether in Maharashtra, Bihar, Tamil Nadu, Uttarakhand, Jammu and Kashmir, Kerala or West Bengal, a careful look at the performance audit of disaster management and flood control works would point to the need for analysis of the root causes of the disease. That root cause many a time is outdated manuals of the management of waterbodies and dams, coupled with a failure to respond to constitutional auditors and the lack of humility to learn from past mistakes and blunders.

For the sake of creating awareness of ground realities among the people, may the tribe of those nameless auditors who studied the Chennai Floods 2015 under the CAG of India and wrote an eminently valuable stand-alone report, as well as of authors like Krupa Ge, grow.

Read the author’s interview here.