The BMTC has more often than not followed the KSRTC in increasing fares. With the latter recently increasing fares, chances of the former considering a revision is a possibility. While that suspense continues, a study by the city-based think-tank Fields of View demonstrates exactly why it makes sense — economically and environmentally — to reduce bus fares.

The study — ‘Scenario based analysis of change in fares for public transport, ridership, congestion and emissions in Bangalore’ — demonstrates through different scenarios (bus fare being the primary variable) just how much Bengaluru could gain, or lose, from BMTC’s decisions.The authors of the study are Yashwin Iddya, Suruchi Soren, Srinidhi Santosh, and Bharath M Palavalli.

Ridership and Revenue

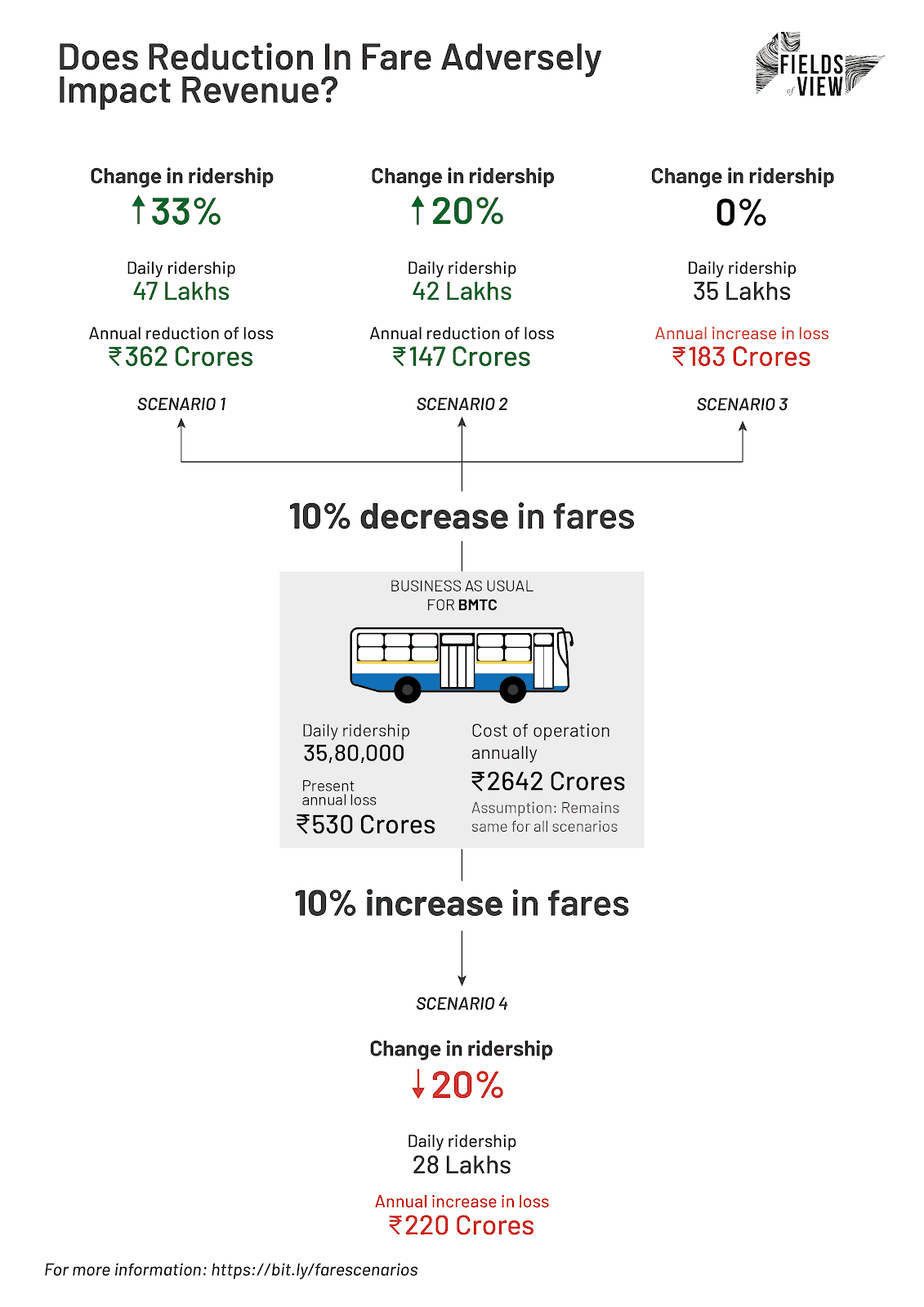

BMTC boasts a daily ridership of 35,80,000 passengers, with an annual cost of operation of Rs 2642 crores while incurring a loss of Rs 530 crores every year.

BMTC boasts a daily ridership of 35,80,000 passengers, with an annual cost of operation of Rs 2642 crores while incurring a loss of Rs 530 crores every year.

According to the study, a 10% decrease in its average fares would propel the share of its ridership by 33%, taking it from the present 35.8 lakh passengers a day to 47 lakh daily commuters. This would reduce the annual loss by Rs 362 crores, the study says.

In the second scenario, a possibility of a 20% increase in ridership (to 42 lakh commuters per day) is considered. This leads to an annual Rs 147 crore reduction in losses. In the third scenario (which is the present one), no increase in ridership is considered; maintaining the 35-lakh daily ridership will cause annual losses of Rs 183 crores.

The fourth scenario pictures a 20% increase in fares. This leads to a 20% decrease in ridership, to 28 lakh commuters a day, and increases the corporations’ annual losses by Rs 220 crore.

The scenarios denote that decrease in fares increases ridership and revenue, while an increase in fares leads to fall in ridership and bigger losses. The third scenario denotes that BMTC, in its present state, cannot increase ridership or reduce its losses.

Carbon Emissions

The next section of the report gauges environmental implications of reducing bus fares, in terms of total greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions.

The first scenario considers increased BMTC ridership of 33%, causing the share of private vehicles i.e. two and four-wheelers to decline by 78.4% and 23.5% respectively, reducing annual emissions by 1.1 lakh tonnes.

In the second scenario, with only a 20% increase in ridership, four-wheelers would reduce by only 47.5% and two-wheelers by 14.2%. This would decrease emissions by 0.7 lakh tonne per year. The third scenario considers a case of 0% ridership in buses, two and four-wheelers, leaving emission levels unchanged. In the fourth scenario, a 20% drop in BMTC’s ridership would escalate the usage of private vehicles to 47.5% and 14.2% for two and four-wheelers respectively. This would increase annual emissions by 0.7 lakh tonnes.

BMTC slashing its fares would thus increase its ridership, decrease the volume of private vehicles, leading to reduction in GHG emissions into the environment. According to the report, an effective and affordable public transport system would reduce the corporation’s carbon footprint.

Congestion

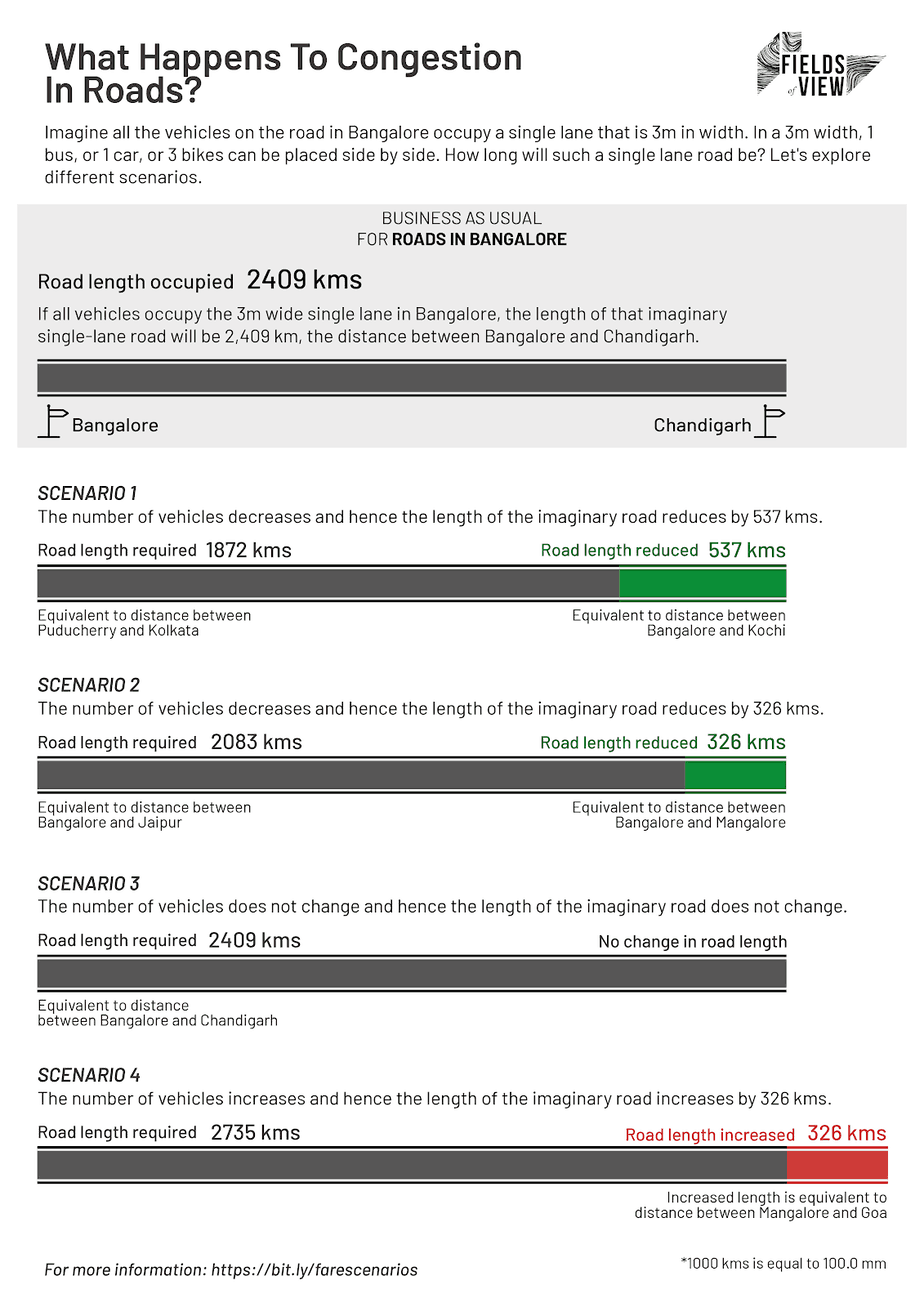

For this section, the study assumes that all four-wheeled vehicles occupy a 3-metre wide space on a single lane on Bengaluru’s roads. It assumes that three two-wheelers would occupy the same 3-metre width. Assuming that the entire vehicular population is on the road, the total length occupied would be a massive 2409 km. This is the same distance between Bengaluru and Chandigarh.

In the first case scenario, increasing public transport usage by 33% would slash the length of the imaginary road by 537 km to 1872 km (the difference in road length being equivalent to the distance between Pondicherry and Kolkata).

The 20% increase in BMTC ridership, as shown in scenario 2, would reduce the queue by 326 kms to 2083 km (while the rest of the distance would be the same as Bengaluru to Jaipur). In the third scenario, as there is 0 ridership, the length of the road remains unchanged at 2409 kms. In the fourth scenario, as BMTC’s ridership reduces by 20% and that of private vehicles increases, the road length increased by 326 kms.

The Way Ahead

The study proposes adoption of various strategies for increased adoption of Bengaluru’s public transport infrastructure. This involves allocation of funds for infrastructure development and cost of operations, subsidised fares though state and Centre-sponsored schemes, private players incentivising public transport to employees, etc.

It also highlights the simultaneous promotion of non-motorised transport and bridging the first and last mile connectivity to increase accessibility to public transportation. The study evidences that increased reliance on public transportation is a step closer to achieving sustainable and green mobility in the city.