Across the globe, numerous cities have reaped the benefits of citizen-led urban planning proposals. Such initiatives consider the needs and aspirations of citizens, ensuring the effective use of open spaces and resources. For instance, in 2013, the Metropolitan Government of Seoul designed an urban regeneration policy focused on improving public, open spaces within the city through active citizen engagement, collaboration, and participation. Today, it is the 3rd best city in Asia.

In a similar effort to revitalise the Nepean Sea Road in Mumbai, the Nepean Sea Road Citizens’ Forum has put forth a proposal to the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC) to redesign a 2.7-km stretch from St Stephen’s Catholic Church to Kamdhenu Lane.

With an increasing population and diminishing land resources, there is a dearth of open spaces in Mumbai. The United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals call for adequate accessible open spaces to make cities safe, sustainable, and resilient. At present, Mumbai stands at a preposterous 1.24 sq. m. of open space per person, as compared to Bengaluru and Delhi which have 17.32 and 21.52 sq.m. of per capita open space respectively.

Read more: Is restricting access to public spaces in Mumbai in people’s best interest?

Regenerating open spaces

The proposal illustrates how additional open spaces can be regenerated within the city by reclaiming land to improve the quality of public spaces. Over the years, redeveloped housing societies have given up a portion of their plot in the form of setbacks mandated by the BMC. Setbacks are open spaces around a newly constructed building. However, to this day, the BMC has failed to reclaim this land and it is being maintained by each housing society. As a result, this space is confined by fences and barriers, rendering it desolate. The proposal aims at bringing these parcels of land back into the public realm, in the form of pocket gardens and landscaping.

In a similar effort to reclaim privatised spaces for public use, Rozana Montiel of Estudio de Arquitectura designed “Common Unity,” a public square for the residents of the San Pablo Xalpa Housing Unit in Azcapotzalco. Originally, the rehabilitation complex had been contained within a series of walls, fences, and barriers, restricting the free use of available public space. In response, the designer’s primary strategy was to “shift the vertical (railing, walls, gates, enclosures) which separate and divide for the horizontal (roof, shelter, floors, passageway) that connects, reunites, and encourages community interaction.” This model shows the possibility of making public spaces open and accessible to the residents.

Read more: What is the way forward for the planning of open spaces in Mumbai?

Identifying infrastructure gaps and discovering solutions

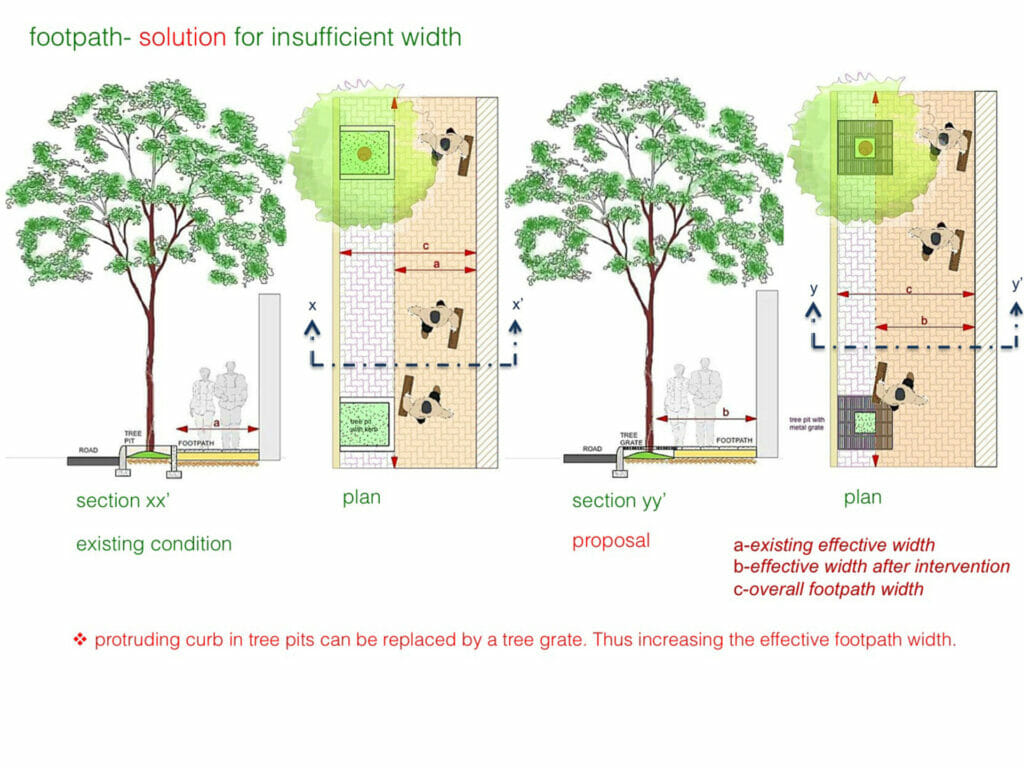

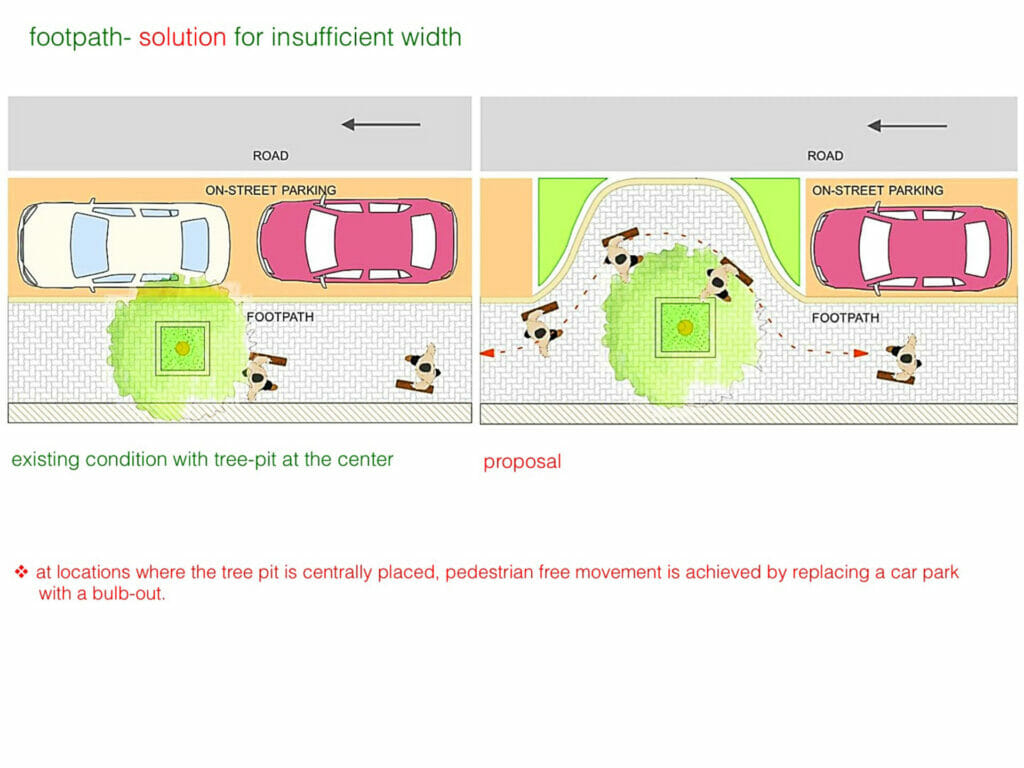

The Nepean Sea Road Citizens’ Forum has identified missing footpaths and areas prone to encroachment by hawkers that hinder pedestrian movement. In several instances, the junction between the footpath and property lines is discontinuous due to damage and neglect, causing hindrance to both pedestrian and vehicular movement. As a response, kerb ramps will be provided at these junctions, enhancing overall mobility.

Furthermore, the pedestrian crossing across the carriageway will be raised, connecting the footpaths to create an integrated walking system. The raised nature of the crossing will also compel vehicles to slow down, therefore ensuring pedestrian safety. With a focus on further improving mobility and pedestrian flow, redundant signages and damaged street furniture will be removed and adequate street lighting, road demarcations, and bus bays will be established all over the 2.7-kilometre stretch.

Additionally, all major junctions and roundabouts will be redesigned to augment accessibility and regulate traffic flow. The proposal also aims to establish a public health clinic to make healthcare accessible to all — specifically, the slum dwellers of the vicinity who are in dire need of medical attention.

A number of Mumbai-based architects, designers, and urban planners will come together to design and conceptualise specific interventions within the proposal — completely in collaboration with the citizens, for the citizens.

Citizens are generally adept at accurately recognising gaps in civic infrastructure as it often impedes their day-to-day functioning. Participatory planning is, therefore, more likely to successfully uplift the quality of a city and ensure the use of public spaces to their utmost potential.

Shared ambitions for a shared future

This model can be adopted in areas across Mumbai — neighbourhood-level meetings can be held where all stakeholders consider their needs and aspirations. A democratic voting system can further help prioritise these requirements and produce a strategic design brief for local architects and planners. Such an alliance between local architects and citizens is bound to be a powerful and impactful one and can go a long way in garnering the BMC’s support and approval. In terms of financial resources, private organisations can be approached to fund the implementation of these projects under their CSR (Corporate Social Responsibility) schemes. For example, the JSW Foundation has supported many public projects across the city such as the ongoing Malabar Hill Forest Trail and the Samatech toilet on Marine drive.

Citizen-driven public projects are a holistic manifestation of the needs and aspirations of the people, creating an inclusive and promising future. Participatory planning can, hence, be used as a powerful tool in revolutionising Mumbai, one neighbourhood at a time.