“My youngest son was born here (near the landfill) and while I was pregnant, I had to rely on the water from the handpump”, says Anita*, a waste picker living in Shraddhanand Colony adjoining the Bhalswa Landfill in Northwest Delhi. If you’ve traveled by road to Chandigarh, you would have seen this is the mountain of trash. “He’s had kidney problems ever since he was born,” adds Anita. “Within 5.5 years, we have had to get him operated six times! Because of the medical expenses, we have to go without ration for a few days. Stomach, skin, and eye problems are the most common amongst the community”, says Anita, showing us the medical reports of her 6-year-old son.

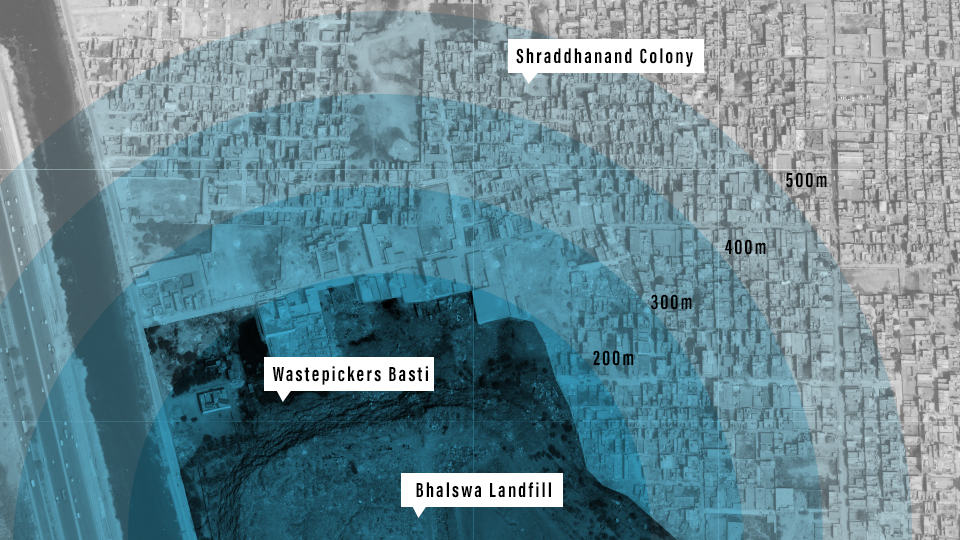

Like Anita and her family of five, 50,000 waste pickers in Delhi living near three major landfills, Bhalswa, Okhla, and Ghazipur, risk their health every single day to keep our city clean. Almost 50% of Delhi is responsible for the 2,000 mega tonnes of daily waste dumped at the Bhalswa landfill since 1994.

Forced to depend on scarce amounts of potable water and living in the vicinity of toxic runoff and leachate, the waste pickers communities living in Shraddhanand Colony share a toxic relationship with the landfill.

A day in the life of a waste picker

Anita’s family, along with 50 other families, reside in self-constructed bastis built by upcycling the waste from the landfill which it receives from various industries and more privileged homes. Discarded cloth, banners, carpets, and shuttering planks provide both refuge and identity to each home in the basti.

Starting late at 10 pm with a torch, a bottle of water, and food to suffice till 5 am, groups of waste pickers climb the mountain of trash every night to collect the unsegregated. During the day, the entire family sits in the small open space in front of their house to segregate the waste and sell them. Plastic wrappers and polythene bags are often cleaned with water from a local hand pump, which assures a higher price for the product. They use the same hand pumps, gushing out yellow frothy water, for a bath, after toiling in the heat at the landfill. Temperatures at the top of the landfill are typically higher due to the methane gas emanating from the waste. While some houses have separate handpumps, typically each handpump is shared by six to eight families. These homes and hand pumps, lie within a 500-meter radius of the landfill.

“In the last 1-2 years, the water from hand pumps has turned from yellow to green,” says Anita. “The water feels like petrol, it smells and is sticky”.

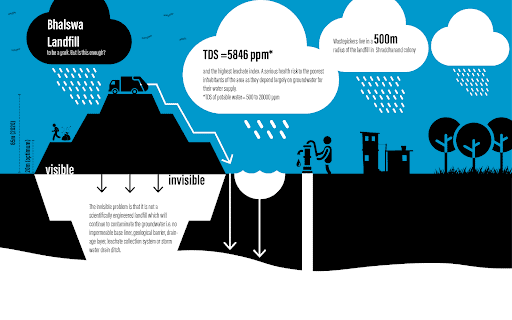

The leachate from this non-engineered landfill percolates through the ground and contaminates groundwater. With lack of sewage disposal systems and leachate control drains in the surrounding communities, the groundwater is further contaminated by percolation of untreated sewage water. The handpump releases yellow water with a TDS (Total Dissolved Solids) of 5846ppm (parts per million), way above the desirable 500ppm fit for consumption.

Observing the landfill at close range, it is almost impossible to distinguish where it starts and where it ends. The ground is barely visible as it is completely covered with trash. Often, and without warning, huge chunks of garbage fall off, endangering homes and lives .

“During monsoons, homes fill with dirty water and we have to wait 2-3 months for it to dry out. So, families tie the sleeping and kitchen platform 2.5 feet above the ground,” shared Anita. The overall air and water quality in the vicinity is dangerous and one can’t stand for too long next to the black runoff from the landfill without getting a headache. The stench of the leachate was perceivable through an N95 mask and the authors wondered how bad it must be otherwise.

The authors were shocked to see laughing children treating the pool of leachate as a river, hopping on top of bags of trash they imagined to be their boats. The lack of playgrounds and healthy open spaces is clearly evident. While the increasing height of the garbage hill seems to be the pressing ‘visible’ problem, they are cesspools of poor sanitation, unclean water, and unhealthy spaces, making visible a problem otherwise invisible.

Read more: Why bioremediation is not a magic pill for India’s overflowing landfills

Home away from home

The majority of waste pickers living next to Bhalswa belong to the Julaha community, also known as weavers, (listed as Scheduled Caste in the Constitution). They hail from rural Bengal who lost their craft to the machine age and moved to Delhi in search of a better life. Mainly Bangla speakers, over the years, they adapted common Hindi words to maneuver through the city.

While they call Delhi their home, the city’s service providers have done very little in the past to extend basic WASH services provisioning to them. Just like Anita’s family, majority of the waste pickers have their various national identifying documents (Aadhar, ration, and voting card)

issued from West Bengal, and are hence treated as outsiders even by the neighboring communities. With no right to the city’s infrastructure and services, they struggle every day with caste and occupation-based discrimination and face challenges in accessing basic services such as water, health, sanitation, and healthy spaces.

“Yahan do porta toilets lage the COVID ke time pe. Jispe inka jhagda hone laga ki use kaun kare, maintain kaun kare. Baadmein unko lock kar diya gaya aur phir hata diya”, narrates Sheikh Akbar Ali, a community leader from NGO Basti Suraksha Manch who has been working with waste picker communities for over 30 years. [Translation: During the first wave of COVID, porta toilets had been installed at a corner where people from all communities could access them. But due to issues of maintenance and community conflict, they had to be removed]

At the same time, Shraddhanand Colony witnessed mass migration during the height of the pandemic. In the authors’ first few visits in March 2021, out of 50 families that used to live along the base of the landfill, only 11 had returned. Faced by a loss of livelihood along with no access to food, water, or relief from the government they had fled to Bengal, where they struggled to earn but could survive.

Read more: Hope anew for Delhi’s Ghazipur landfill as PMO steps in

Water wars: The price of water

As one enters the basti, containers of all shapes and sizes can be seen lined outside houses for collecting water from tankers. Earning around Rs 5,000-7,000 per month as a family, almost 25% of Anita’s meagre income is spent in procuring potable water used for drinking and cooking from the private tanker that otherwise wouldn’t serve their community. For all other needs, they are dependent on the contaminated groundwater from the handpumps. This contrasts with parts of the same Shraddhanand colony and the pakka houses on the opposite side of the road having access to piped water supply from the government.

What the authors found most touching, during their study around the WASH challenges was that the first time they met Anita and her family, they were offered bottled water – which is a luxury for the residents of the community.

“Yahan toh ladai hai, ki in logon ko paani kyun dein. Agar road pe tanker lag jae na, toh inko paani nai milega.”, said Sheikh Akbar Ali. [Translation: There is a fight amongst the people of the neighborhood, why share water with these people. If there is a tanker on the main road for the entire neighborhood, they will not get water]

Every week, on days fixed by groups of six families each, a private tanker comes to the basti to supply almost 350 litres of potable water for the entire week. In terms of water availability, it works out to 1.7 litres (~ 2 bottles) of water per person per day. Or one sixth of what the livability standards like the National Building Code suggest.

Such shocking figures only confirm that in the absence of adequate quality water supply, people are forced to drastically reduce their water requirement, and depend on unclean water to meet their needs pushing them further into health-related risks such as dehydration and malnutrition.

The following water pricing comparison is based on data from field and secondary sources:

| Water Source | Price per litre (INR) |

| Tanker | 2.22 |

| Mineral water bottle (20 litres) | 4 |

| Swajal water ATM | 3.33 |

| DJB central piped supply | 0 + service charge for 20,000l per month |

This shows that piped water supply is the cheapest and only the privileged few get access to it, while the most vulnerable are left to fend for themselves and pushed further into the poverty cycle.

Equal cities and the Right to Life

Following the Okhla Landfill’s example, the landfill at Bhalswa is also being turned into an Eco-Park by the NDMC. Bio-mining, greening the surface, reduction in height, slope stabilization and setting up Waste to Energy (WTE) facilities are some of the measures being taken up. While these may be portrayed as the best solutions to tackle the landfills, they do not follow Solid Waste Management Rules of 2016 and are far from being sustainable. These cosmetic solutions visually reduce the volume of waste, but the burning of unsegregated waste by WTE plants increases air pollution.

There have been many discussions about residents of Delhi not knowing where their garbage ends up, but the enormous impacts of the landfill on the lives of people living around it have largely been overlooked. The very people who clean our city are the most vulnerable as they do not have access to basic services including drinking water.

Read more: Humanizing the lives of waste-pickers in Deonar

The authors’ investigations on the field raise some fundamental human rights questions about the creation of equal cities for all citizens- especially those who are marginalized. Why should one have to be identified by a document in order to avail basic services? Is the right to life reserved only for those who vote in that constituency? Do waste pickers not have the right to clean drinking water? While India works towards the UN Sustainable Development Goals, we wonder whose development they apply to? Who then has the right to saaf paani** and healthy environment?

*Names changed to preserve anonymity

**saaf pani in Hindi means clean and safe water

Note: This article has been written with the inputs from Accelerating Access Coalition (AACO) and other third party resources. Accelerating Access Coalition (AACO) is a consortium that aims to prioritize the agenda of improving citywide inclusive and resilient access to Water, Sanitation, Hygiene (WASH) and Healthy Spaces for improved health and well-being outcomes and economic prosperity for all. However, all views expressed by the author(s) in the article are of his/her/their own and AACO does not assume and hereby disclaims any liability to any party for any loss, damage, or disruption caused by views, errors or omissions of the author(s).