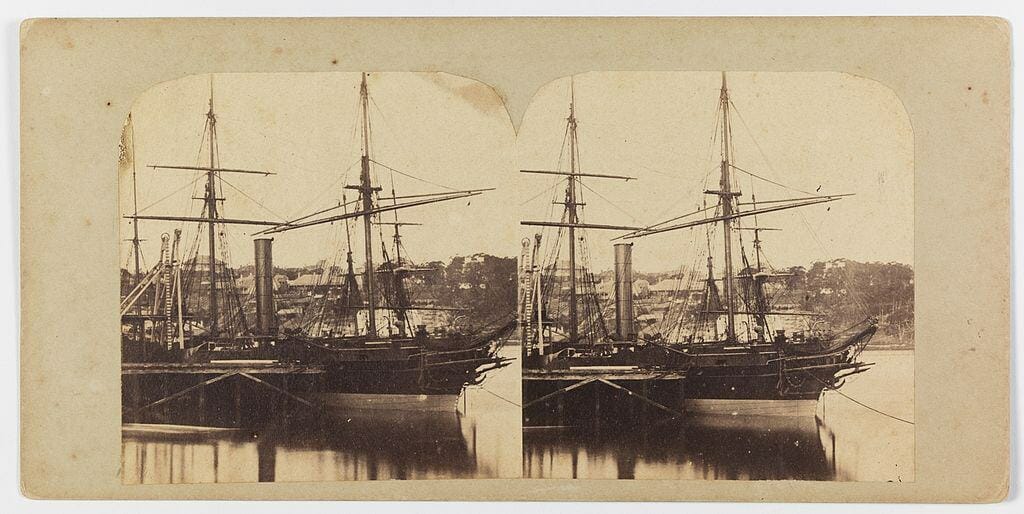

The history of water transport in Mumbai dates back to the Seven Islands of Bombay, which were under Portuguese possession. In 1661, they were handed over to the British, and between 1820 and 1857, the islands slowly became what was then known as Bombay. It was with the opening of the ‘Overland Route’, a transportation route that made it possible to travel to Europe, that Mumbai built its first steamer in about 1830. The route cut travel time down from five months to one and a half.

By 1850, Bombay came into being. Trade between Europe and India was expanding, with the opening of the Overland Route, and the city’s coast was soon lined with wharfs, docks and godowns.

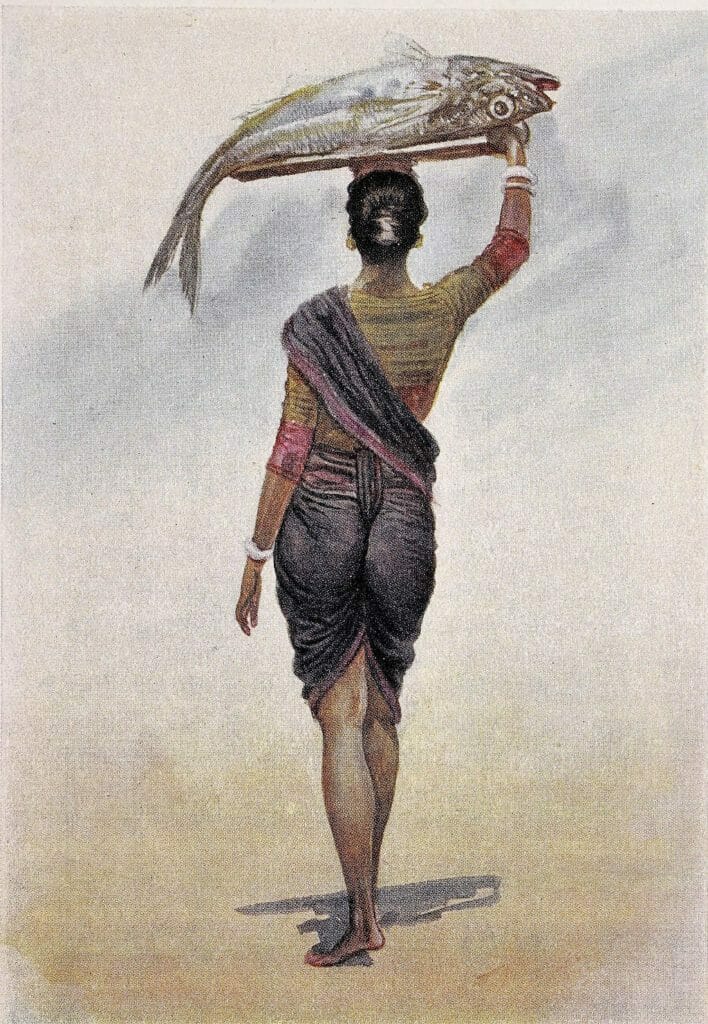

But this was not the city’s earliest relationship with its water. For over 500 years, fishing communities have lived along the coast of the seven islands, Bombay, and now Mumbai. The name ‘Mumbai’ is believed to have originated from the community, as far back as the 16th century, whose deity Mumbadevi inspired the colloquial use of ‘Mumbai’. Since the late 1800s, Kolis traded via the Sassoon Dock in Old (South) Bombay, built on reclaimed land (when the East India Company began its project to build a city out of water) in 1875.

Earliest inhabitants

The Son Kolis of Bombay first arrived on the land(s) in the 12th century AD, when they migrated from the banks of the Son and Vaitarna rivers, where they built caves and boats. Invasions and vulnerability forced them to Bombay, where they found their identity as fishermen.

As Bombay continued to expand, and its land reclaimed, Kolis were pushed to pockets in the city now known as Koliwadas. They became central to the economy of the city, involved in the collection and distribution of fish. Needless to say, Mumbai’s earliest relationship with its waters was developed and maintained by them.

Read more: Mumbai’s Kolis fight to (re)claim their home

A new imagination, the country’s first water taxi

Now, close to 400 years later, Mumbai’s industrial – and transportation – development has led to the country’s first water taxi that will connect Mumbai with Navi Mumbai. For the first time, a direct connection between the twin cities will be facilitated by a shorter travel time.

Jointly developed by the Mumbai Port Trust, Maharashtra Maritime Board (MMB) and CIDCO, at a cost of Rs 8.37 crore, the taxi is set to reduce travel between both cities from 90-100 minutes to under 45 minutes. Current routes of the speedboats announced are Navi Mumbai’s Belapur and South Mumbai’s Domestic Cruise Terminal (DCT), Belapur and Elephanta, Belapur and Jawaharlal Nehru Port (JNPT). The boats will run from 8 am to 8 pm, 330 days a year, except a few days during the monsoon season. Not all Mumbaikars will be able to afford the journeys, however, since fares range anywhere between Rs 800 and Rs 1,200.

A total of eight boats have so far been allocated to the project, those include speed boats with carrying capacities of 10 to 30 passengers and catamarans with carrying capacities of 65 passengers.

Work for the project began on Belapur Jetty in January 2019. On February 17th 2022, CM Uddhav Thackeray at the inauguration highlighted Mumbai’s history of setting examples for transport and trade. “The country’s first railway service was started by the British between Mumbai and Thane before it quickly spread all over India. The city always sets a trend that is emulated by the rest of the country,” he said, in the presence of Union Shipping Minister Sarbananda Sonowal, who flagged off the service.

The root of the project lies in Mumbai’s traffic congestion. Almost daily, commuters in the city find themselves trapped by roads and bridges unable to contain a 20 million (and counting) population. In 2021, the city ranked 5th in the global ranking of urban congestion, according to a Traffic Index report by global location technology firm TomTom. The suburban railway network alone carries almost 7 million daily passengers. Given the scenario, the discourse around the need for inland water transport has been gaining steam for some time now. But, what about the impact to the water?

(Another) Environmental impact?

In 2019, a study by the Indian Institute of Technology, Bombay (IIT-B), found that Mumbai’s waters might have more plastic than fish by 2050. The report warned that ‘nearly 700 marine species were threatened by rising pollution’, ‘plastic pollution is destroying the city’s mangroves’, and ‘in the past 70 years, plastic consumption has increased by 99.57%’.

Before this study, an application submitted by environment group Vanashakti before the National Green Tribunal (NGT) in 2018 claimed that Mumbai dumps 80 to 110 metric tons (MT) of plastic waste into drains and water channels every day. This waste, if not collected (and they aren’t), empty out into creeks, rivers and the sea. These issues are also the cause of the city’s infamous flooding problem and coastal erosion.

Data for the environmental impact – if any – of daily ferries to and from Mumbai is lacking, but it is widely asserted that the several coastal projects currently in development have already left a mark on Mumbai’s debilitating environment. In 2011, norms for the coastal regulation zone (CRZ) were revised to allow more commercial activity closer to the tidal line. This also meant easier reclamation and the development of land. This was additionally supposed to help the BMC reclaim 90 hectares of land for the widely criticised – yet awaited – Coastal Road Project, a large chunk of which has made headway.

“From the ongoing projects along Mumbai’s coast to the chemicals dumped into the sea (some petrochemical industries discharge effluents into the sea without treating them), everything has repercussions for the fishing community,” Nandakumar Shivdikar, the President of Sewri Koli Samaj (A community for the traditional fishing community in the eastern suburb of Mumbai), told Citizen Matters Mumbai.

While many applaud the inauguration of the water taxi, marking it as a solution to the city’s traffic woes and an alternative to building more roads, it is yet to be seen whether it will achieve this without more impact on Mumbai’s precious sea.