Taufiq, an electrician in Shivaji Nagar, sits in his shop surrounded by wall-mounted fans. Despite other shops like his in the area, he gets at least 2-3 fans for repairs daily. As Mumbai is headed into summer with temperatures touching 40 degrees Celsius in March, it’s no secret why Taufiq gets business everyday. The general ceiling fans, he says, are not cutting it anymore.

“Most people here don’t have ACs or coolers, so they look for a fan that is fast,” explains Taufiq, showing me a fan unlike any other in the market. “We assemble this here. The motor comes from a washing machine and the blade is from an AC fan. It’s then attached to a rod and connected to the ceiling fan’s shaft.”

The relatively powerful motor and curved blades, in contrast to a typical ceiling fan’s horizontal ones, are supposedly better at cooling. A resident in the house next door confirms this, having had the fan in her house for over half a year now.

Confined to the houses in the narrow lanes of Shivaji Nagar slum cluster, the fan has been in circulation for three years now. It is sold for Rs 1,500, although the price goes up in the summer months to Rs 2,000. It is a product of the conditions that define the area: financial insecurity combined with oppressive heat.

Urban heat is one of climate change’s most potent effects in Mumbai, and the M-East ward, located in the southeast of Mumbai, bears the brunt of it. 38% of its population is exposed to surface temperatures greater than 35°C, according to the vulnerability assessment done for the recently launched Mumbai Climate Action Plan (MCAP).

Uniquely disadvantaged

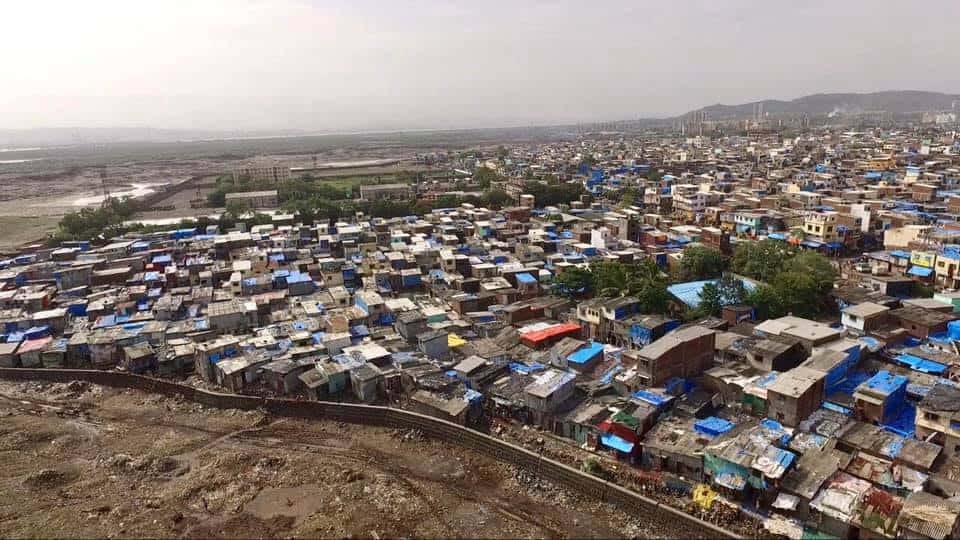

The majority of the M-East ward’s population, about 84.9%, lives in densely-packed informal settlements. Shivaji Nagar is the largest of the slum clusters, housing over 2,00,000 people in structures rarely more than two storeys tall.

“We are 10 people in a house,” says Nashra, a resident who lives in a small room on the ground floor with six children, her aunt and grandparents. They are all on the floor at 2 in the afternoon, stretched out or cross-legged. Because there are no windows or outlets for ventilation, the front door remains open. A curtain hangs partly in the doorway, dimming the room and shielding it from the street.

Nashra’s family is fasting for the Islamic month of Ramadan, which entails refraining from food and drink between sunrise and sunset. It makes the heat harder to bear, but their routines have shifted around to make it easier. “We get up late, around 12 or 1 AM. The rest of the day is spent in praying and housework,” she says. Her work as a community civic teacher with the NGO Apnalaya is on pause. The children busy themselves in play till late evening, moving onto the open street as the heat wanes.

The sun shining down upon Shivaji Nagar is no different than the one over the rest of Mumbai. But the infrastructure on ground results in a very uneven picture of urban heat, with informal settlements at least 5-6 degrees Celsius hotter than residential complexes in the area.

A significant reason for this is building material, especially that of roofs. Metal is a good conductor of heat, absorbing it more readily and storing it for longer periods, and is more commonly used in informal and low-income settlements in the city, including Shivaji Nagar. According to the Census 2011, roughly half of the roofs in the M-East ward are made of asbestos and metal. The majority of the remaining use concrete, although this is likely to have increased due to a greater awareness of the cancer risks associated with asbestos.

While the greatest effect falls on those directly under the roof on the top floor, the large amounts of heat radiated from the roofs is not contained. This means that even if the city as a whole is experiencing normal maximum temperatures (under 33 degrees Celsius according to the IMD), the condition in informal settlements could be close to that of a heat wave (37 degrees Celsius).

Adaptation

Nashra’s family’s main line of defence against the scorching temperatures are three ceiling fans. “It gets unbearably hot when we cook, because it’s completely packed. But otherwise, we manage,” says her aunt, Hussainbi. This often means taking multiple baths a day and sleeping directly underneath the fans on the floor.

The latter is an extremely commonplace practice in the area due to the space crunch. Homeowners who can afford it go the extra step and tile their floors, supposedly adding to the cool.

An air conditioner is not an option, and not only because it is prohibitively expensive. Many houses in the neighbourhood use “stolen” power, routed through illegal lines by gangs. Adding an energy-intensive AC would overload the line and possibly alert officials to the theft.

Nashra’s family made the switch to a metered connection two years ago, due to the threat of a hefty fine. “Our monthly electricity bill is already very high at Rs 3,000-4,000. We use the fans only when we need to, because we know we’re the ones who are going to have to pay for it,” she says.

But Nashra has it comparatively easier than many others in the ward. She lives in the section of the slum that developed in a somewhat planned manner with proper streets in between. Her house receives enough water for the entire household in the morning, compared to 45% of the households don’t have a drinking water source within their premises, and 35% lack toilets. Only 54% have access to clean cooking fuel.

Read more: Rising temperatures in Mumbai call for mitigation measures, but where are they?

Working under the sun

Left with no choice, the prevailing attitude towards the unrelenting heat in the area is one of endurance.

Sayed Ahmed, a fruit vendor, is constantly spinning a handkerchief at his face to direct air towards it. He continues sweating profusely, as the manual fan is no match for the crowds elbowing through the narrow market lane on Road 11. Shivaji Nagar has a large Muslim population, and they are out in preparation for Iftar, the meal to break the fast. By 4 PM, the eateries by his side have fired up their grills and woks of oil. The surrounding air wavers, and complaints about the heat float through.

Ahmed too is fasting and admits he’s not feeling the best. Still, he stands by his hand cart from 3-7 PM everyday, occasionally spraying his fruits with water. “They come from a godown with AC, and they’ll rot from the inside under the sun. I try to sell them all in a day, even at lower prices, because otherwise they might go to waste,” he says.

The attitude towards his body, however, is one of resignation. “I have to bear it,” he says. Others echo this sentiment, treating the heat as matter-of-fact. Bashir, who arranges mandaps for weddings, says, “I feel the heat, but what can I do? I have to handle it for work.”

The years-long exposure to heat wave-like temperatures can explain this, according to Dr Farid Shaik, a doctor at Shifa Clinic in the area. “An outsider will get sick here within 24 hours. But the people here are born and brought up here, and have become habituated to the heat. It doesn’t affect them as much,” he says.

Other times, escaping the heat has a bearing on productivity. Construction workers and labourers often make arrangements with their employers for the summer months, working early mornings and late evenings instead of the peak afternoon. The owner of the vacant Shahnai wedding hall, Bashir’s workplace, keeps the hall open during the day so men can drop in to take a nap.

But as the effects of climate change continue to mount, the number of days that see high temperatures are only going to increase. By 2040, high urban heat days (exceeding 32°C) will be a staple of over half of Mumbai’s year, according to projections by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). Enduring the heat will be an inescapable part of earning a livelihood.

Temporary solace

It is perhaps only children that are out on the streets by choice. They are at every corner, somersaulting on a discarded mattress, running and even digging through gravel. 10 year old Ayaan, chasing his friends on a bicycle, shyly says he forgets any discomfort when absorbed in play.

When asked if the heat is particularly harmful for children, Dr Farid refutes it, saying, “Life is very unhealthy here. But the factors that cause the heat are more important.” He points out that most of the houses have an area of barely 150-180 sq ft, whereas the healthy minimum is 275 sq ft. The absolute lack of ventilation in them restricts oxygen circulation, far more damaging to a child’s developing brain.

The near complete lack of greenery in the slum provides no relief. “People go out on the road to look for a place to sit and relax. But there is no shaded space to peacefully sit outside either,” says Shaikh Faiyaz Alam, a resident. The result is that people cling on to slivers of shade available, in parked rickshaws and the curbside of shops. This is easier in the midst of the tightly packed lanes, than on the wider roadsides without the looming shade of a building in sight.

Faiyaz runs the NGO New Sangam Welfare Society, helping people with local issues like water and electricity connections. He has received no direct complaints about the heat, but he’s gotten requests for greenery and against the pollution.

On this front, however, the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC) claims to have made an effort. Ayesha Shaikh, a former corporator of the area, says they had organised a plantation drive in the premises of the BMC school.

Faiyaz points to a row on the road where the trees had been planted in the past, but have been uprooted for the construction of a bridge. “If the government worked on the environment and greenery here, the heat would be controlled. But no work gets done here. Many campaigns start, like the Majhi Vasundhara Abhiyaan, but they do not reach here,” he says.

Trees are needed here to counter the heat..

Great article Sabah!