The cranes and backhoes are out. The boats, trawlers, and the beach walkers are waiting. The sea around Mumbai may be calm, but with multiple infrastructure projects forthcoming, its coast is definitely not.

-

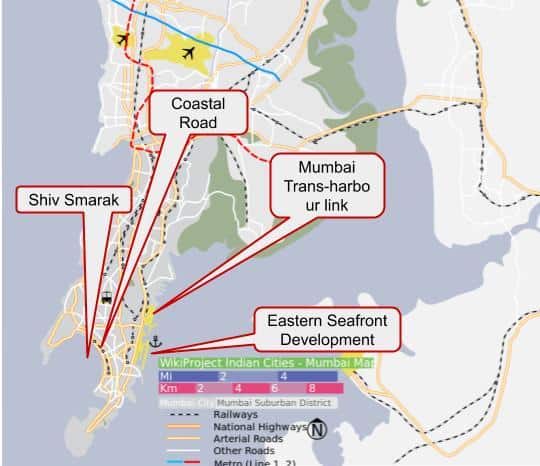

- On the west is a Rs 12,000-crore eight-lane coastal freeway known as the Coastal Road Project which will run from South Mumbai to the northern suburbs.

- On the east, known so far for its petrochemical industries, dusty roads, and a flamboyance of flamingos in the mudflats, the Mumbai Port Trust has drawn plans to replicate London’s Hyde Park, reclaiming a 100 hectares from the sea.

- Mumbai’s eastern coast’s adjacency to Navi Mumbai has also been considered for a Rs 22,000-crore, 22-km and Mumbai Trans-Harbour link—a sea link from the eastern coast to Nhava in Navi Mumbai.

- A 300-acre park to be built after reclaiming land between Nariman Point and Cuffe Parade in South Mumbai.

- And the most contentious, of course, is the Rs 2,500 crore Shiv Smarak—a monument for Chhatrapati Shivaji, the Maratha warrior king, in the middle of the Arabian Sea.

Clearly, the heady battle for Mumbai’s coast is in character with the country’s ongoing elections. It reflects a general understanding among the government and policy makers that solving the city’s congestion and traffic problem solves everything else.

But in reality, these projects will only expel the city’s traditional fishing community and cause environmental degradation due to land reclamation. And despite the humongous expenses and effort, mobility and quality of life for ordinary citizens is unlikely to improve.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi performing jalpoojan of Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Memorial in the Arabian Sea, 4 km off Mumbai’s Marine Drive. Src:cmo.maharashtra.gov.in

Why should more roads lead to South Mumbai?

Cities shape and are shaped by their natural environment. So even as Mumbai has grown into one of the world’s densest cities by snatching land from the sea, flattening mountains, and filling up marshes, some of its inhabitants, especially the Koli fisherfolk, have remained dependent on the sea.

Most agree that sustainable cities must be compact and dense because the more widely distributed people are, the more expensive it is to provide them with resources. The population dispersion also increases transport costs and transport-related pollution. And so, there are environmental consequences of allowing unrestricted growth of cities. Especially, when unrestricted growth, as in the case of the coastal road project or the trans-harbour link, means adding more roads and flyovers.

The official position of the government on the road projects is to ease connectivity, congestion and reduce traffic. But architects and planners call this nothing but an ostrich policy. Architect Jagdeep Desai says,“Mumbai’s existing roads are not equipped to handle the traffic that its new highways, freeways and sea links will spew out.” But even if they were, there is enough evidence to prove that more roads, low parking and no congestion costs only incentivise car ownership and increase traffic, not reduce it.

The second concern with these projects is a lack of holistic urban planning. Desai points out that “the idea of building special economic zones and business districts in the city’s suburbs was to develop other parts of the cities”, then why should more roads lead to South Mumbai?

There is already an ongoing 172-km metro project which aims to connect the entire city. The coastal road, therefore, is wasteful because the shoddy urban planning has resulted in a situation where, Roshni Udyavar Yehuda, an architect who specialises in environmental design, says, “two ongoing projects—the metro and the coastal road—will compete with each other”.

Existing crumbling infrastructure would also compete for attention. While public infrastructure development might not always be at the expense of other projects, the poor track record of the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC) is such that new projects necessarily mean that existing infrastructure is neglected. The recent foot over bridge collapse outside Mumbai’s iconic Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj terminus or a 2017 stampede that killed 29 at Mumbai’s Prabhadevi local railway station are examples that prove how everything else stands hanging while elites are served via impossible road networks.

The road projects, in short, will do little to solve the existing commute problems of citizens. They will only throw the community dependent on the coast under the bus, and leave them at the mercy of courts and politicians for employment and rehabilitation.

The bigger loss

In 2011, the coastal regulation zone (CRZ) norms were revised, allowing increased commercial activity closer to the tidal line, easier reclamation and development of land, higher FSI for nearby buildings, and other such benefits. It’s these relaxed norms that will help, for instance, the Mumbai Port Trust to develop the eastern part of Mumbai, or the BMC to reclaim almost 90 hectare land for the coastal road.

Src: mumbaiport.gov.in

Even as arguments for relaxed regulations and increased FSI are valid to free up land and increase supply, hidden costs are applicable. The fisherfolk of Mumbai need this coast for their livelihood but because of the new norms, land which should be rightfully theirs can be potentially usurped and distributed for development by the state.

“From the ongoing projects along Mumbai’s coast to the chemicals dumped into the sea (some petrochemical industries discharge effluents into the sea without treating them), everything has repercussions for the fishing community,” says Nandakumar Shivdikar, the President of Sewri Koli Samaj (A community for the traditional fishing community in the eastern suburb of Mumbai).

Some Kolis have already stayed out of water this fishing season because BMC began the construction of a jetty for the coastal road. Sumit Patil, a fisherman at Worli Koliwada, says, “BMC wants us to alter our traditional methods of fishing along the coast for deep sea fishing. Not only are we not prepared for it, it’s also not tikao (sustainable).” Industrial, unsustainable fishing has led to a decline of fish stocks around the world but the Koli community, whose many generations have remained dependent on the sea, understands preservation. However, the fisherfolk are far too divided to be able to mobilise themselves like the Marathas (an upper-caste community in Maharashtra who protested for reservations) or even distressed farmers for resolution.

“We are not putting up a united front, and so, during elections, even as contesting politicians are promising to look after us, each koli will vote for whomever he/she pleases.” Some, however, also talked of boycotting the elections. One report says that, despite the boycott, an average 48 percent voting was recorded in Worli Koliwada, another found that nearly half of the 41,000 voters didn’t vote or voted for NOTA.

Their distress, along with that of the tenants on the eastern coast of Mumbai who can be evicted due to the eastern seafront development, is a talking point for Milind Deora, the former Congress MP who contested from Mumbai South. While Arvind Sawant, the sitting Shiv Sena MP from Mumbai South, counts the coastal road and the progress in development of the eastern seafront as his achievements, Deora has been calling the development plans disconnected from the city’s interests and has promised to oppose the eviction of tenants from the eastern coast.

Still, it is representative of India’s electoral democracy that even as politicians make tall claims, citizens are unlikely to depend on them, turning instead to the courts. In the case of the coastal road, too, it’s the Bombay High Court that, listening to a public interest litigation, recently ordered the BMC to stop the work and maintain status quo. BMC has challenged the order, mentioning that delay would cost Rs 10 crore per day.

Hidden environmental costs

There’s unanimous outrage against the coastal road because of how needless the project is, but this cannot be repeated of the development of the eastern seafront. “Swathes of land are currently lying unutilised in the east of a land-starved city like Mumbai,” Sourabh Jani, a researcher and resident of Wadala in eastern Mumbai, says. But it’s the reclamation needed for any such project, not the development in itself, that raises the hackles of most.

Debi Goenka, an environmentalist, explains that the reclamation will kill marine life and then wreak havoc for the rest of the city. “The reclamation would be at a height higher than the land level which would have grave repercussions for natural drainage. Water falling on the reclaimed area will fall on the lower level and flow into the city,” he says. “It’s also possible,” Goenka adds, “that the natural drains that take water to the sea get blocked”, which would be catastrophic for a flood-prone city like Mumbai.

Architect Hussain Indorewala has pointed out that the coastal road’s environmental assessment study noted that “if land had not been reclaimed for Bandra Kurla Complex, the destruction of the 2005 floods would have been much less.” The narrowing of the city’s Mithi river’s mouth, too, contributed to the flooding.

Polluted Oshiwara river in January 2006. Pic: Jan jörg, Wikimedia

But it’s not just the reclamation, there’s also a systematic erasure of Mumbai’s rivers. The BMC, Goenka says, doesn’t recognise the city’s water bodies. “There are no rivers in Mumbai, there are drainage channels. They don’t show rivers, creaks, streams as that. They call them nallahs (a sewage channel) which are then treated similarly.”

As a result, flooding is apparent every monsoon, but that’s not the only environmental cost. The cost of air pollution, too, made severe by reducing green cover, is unseen. If the metro was going to reduce the pollution by ferrying 11 million travellers, the road projects will increase it. Add to this the cost of reclamation, which will damage marine life and the life of the community dependent on fishing.

And even if the environmental costs are ignored for a second, none of these projects will help the city’s liveability index. It will only negatively alter the city’s coastline and do little about the lack of existing amenities such as open spaces or broken or non-existent footpaths.

Developing a tin ear

It’s apparent that what Mumbai needs is holistic planning and not a random road project that connects points A and B. But holistic and sustainable planning is a pipe dream because of the way the city is governed. Multiple agencies are involved in urban planning and execution in Mumbai.

Goenka says, “MMRDA is a planning authority, BMC is a maintaining authority. MSRDC, MSRTC, MHADA, all these agencies are free to propose schemes they want to.” Except BMC, these agencies operate at the state level and do not coordinate or talk to each other.

Schemes are proposed, development is initiated, but there is no higher-level decision making involved. Udyavar Yehuda explains that “the major difference between Mumbai and a city like Paris or New York is that the mayor is not a nominal head. The mayor has planning, execution and financial control of what’s happening in the city. The mayoral office and council takes responsibility for projects and coordinates for its execution. But the BMC, for instance, has only executory and maintenance powers despite being the one that collects taxes. There is no one single agency or executive head with vision for the city [who would also be] responsible for its holistic planning and implementation.”

There’s another major difference between global cities and Mumbai: The others try to be future ready while we live in the past. “Water levels are rising”, Goenka says, and soon, “there’ll come a point when we’ll have to think about evacuating South Mumbai.” Take just one example—it’s progress in Mumbai when we treat the wastewater before dumping it in the sea. There’s still no talk of reusing it. “Due to climate change, you could have sea water entering Mumbai through sewage channels,” Goenka says. “But we’re not prepared.”

“There’s consideration for no one except the elite”, Shivdikar concludes. “And the original inhabitants, the Kolis, are either quitting their profession or the city”.

| This article is part of a series produced under the Citizen Matters – Sustainable Cities Reporting Fellowship, supported by Climate Trends. |

A common man works hard all his life to make his livelihood and shelter

45,00,000 common men(citizens) have similarly worked hard all their lives and have taken shelter in mbpt and have paid thier hard hard earned money in terms of pagdi

(Most of the recent buyers have paid stamp duty and registration to the state government also.)

Today , the mbpt is making misuse of law and have been sending exorbitant amount dues notices and eviction orders. Just to conclude their thousands of crore worth projects.

If these 45 lakh people are evicted, then the state will be out of gear as their shelter will be at stake. There are equally 45,00,000 more people who are making their bread and butter in this area between Colaba to Wadala that falls under mbpt.

they will be left jobless. How can state or country of afford this kind of situation

A common man works hard all his life to make his livelihood and shelter

45,00,000 common men(citizens) have similarly worked hard all their lives and have taken shelter in mbpt and have paid thier hard hard earned money in terms of pagdi

(Most of the recent buyers have paid stamp duty and registration to the state government also.)

Today , the mbpt is making misuse of law and have been sending exorbitant amount dues notices and eviction orders. Just to conclude their thousands of crore worth projects.

If these 45 lakh people are evicted, then the state will be out of gear as their shelter will be at stake. There are equally 45,00,000 more people who are making their bread and butter in this area between Colaba to Wadala that falls under mbpt.

they will be left jobless. How can state or country of afford this kind of situation