This July, the BWSSB (Bengaluru Water Supply and Sewerage Board) had warned that Cauvery water supply to the city would stop by September. Rainfall was extremely low, and water levels in the Cauvery reservoirs had plummeted. But come August, the scenario turned around completely.

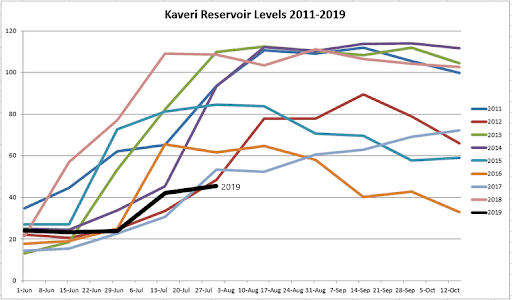

The two-and-half months of monsoon this year has been strange. In July end, while compiling the storage levels across all four Cauvery reservoirs in Karnataka – Harangi, Kabini, Hemavathi and KRS – I found that we were staring at the lowest water levels this decade!

As the KSNDMC (Karnataka State Natural Disaster Monitoring Centre) does not provide data before 2011, I had to be content with data from just this decade. This is what the reservoir levels looked like on July 31st.

Cauvery reservoir levels was extremely low till July 31st. Source: ksndmc.org

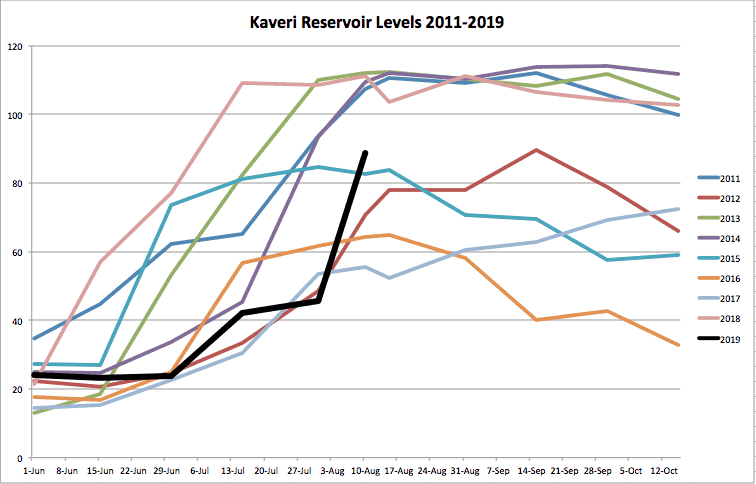

While tweeting out this data, I had expressed a wish for “rains, substantial rains!”. And then, August happened, and that’s what we got – substantial rains! By 10th August, intense rains had lifted the reservoir levels suddenly, and we were looking at the likelihood of full reservoirs in a few days.

As of August 10th. Source: ksndmc.org

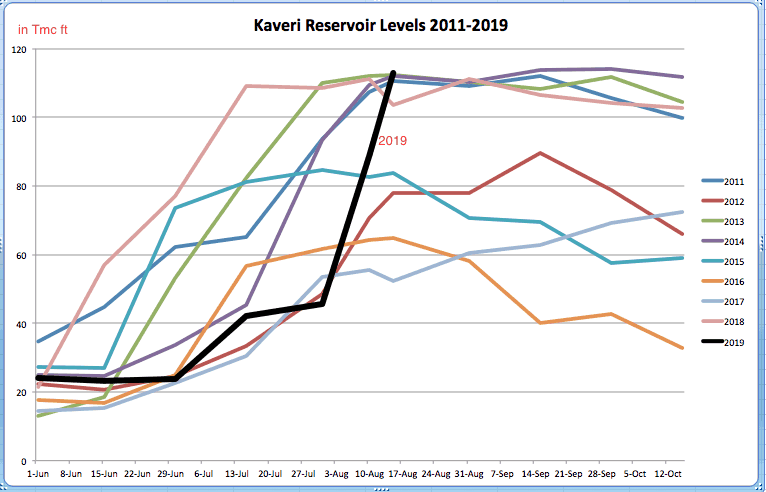

The trend continued, and by August 15th, the four reservoirs were full.

Source: ksndmc.org

Districts like Kodagu felt the wrath of these sudden rains. But despite massive floods and destruction, these areas still had rainfall deficit. For example, Madikeri taluk in Kodagu had 50 percent rainfall deficit when August rolled in. Post-flooding, on August 15th, Madikeri still logged a deficit of 24 percent. How? The answer is, intensity of rains. What is usually received over a month was received over 3-4 days. And that’s when things broke down.

We should be happy that we have a normal monsoon year in terms of numbers, except that it leaves in its wake massive floods, lost lives and lakhs of people displaced!

What do the current reservoir levels mean for water supply to Bengaluru?

From the Cauvery, around 1450 Million Litres of water per Day (MLD) is pumped up to Bengaluru. This translates to around 1.5 TMC (Thousand Million Cubic Feet) of water per month, or 18 TMC per annum.

Given the current storage of 104 TMC in the Cauvery reservoirs, this should be comfortably met, at least till next June. However, water in the reservoirs is not meant just for Bengaluru. A lot of water is allocated for agriculture, ecological flow and for release to Tamil Nadu. For example, in October 2018, the reservoirs had over 100 TMC water. Yet, they ended up with just 12 TMC by the end of this May, since both the northeast monsoon of 2018 and the pre-monsoon showers in April-May had failed spectacularly.

In any case, Cauvery meets only around 50 percent of Bengaluru’s water needs. The city’s total water requirement is around 2000 MLD, based on the assumption that a person uses 200 litres per day on average.

Of the 1450 MLD that is routed from Cauvery to Bengaluru, a lot is lost in transmission. BWSSB estimates loss of around 48 percent or 685 MLD per day, considering both leakage and pilferage (water that’s used, but is not metered or paid for). Unlike leaked water, pilfered water does serve someone’s needs. Hence, assuming even 1000 MLD of Cauvery water reaches the city, the remaining 1000 MLD comes predominantly from groundwater, through borewells.

How will rain affect Bengaluru’s groundwater levels?

In Bengaluru Urban district, rainfall is still at a deficit of 33 percent. However, of the four taluks in the district, the deficit is highest in Anekal at 55 percent. Bengaluru North taluk has the least deficit, at 18 percent.

| District | Southwest monsoon rainfall pattern 2019 (June 1st to August 15th) | |||

| Taluk | Normal | Actual | Deficit % | |

| Bengaluru Urban district | 222 | 148 | -33 | |

| Bengaluru North | 223 | 183 | -18 | |

| Bengaluru South | 226 | 159 | -29 | |

| Bengaluru East | 217 | 131 | -40 | |

| Anekal | 217 | 96 | -55 | |

In the whole state though, only 42 out of 176 taluks listed in the KSNDMC website – that is, just under a quarter – are shown to have deficit. No taluks have been categorised as having scanty rainfall. ‘Deficit’ taluks are those were rainfall is less than 59 percent of normal rains; taluks with worse shortage are categorised as ‘scanty’.

This year, most of the ‘deficit’ taluks are in South-Interior Karnataka, around Bengaluru Urban, Bengaluru Rural, Chikkballapura, Kolar and Ramanagara districts. Given that the main part of monsoon still lies ahead for these taluks, they should likely pick up.

But in any case, the city’s groundwater situation is unlikely to improve dramatically this monsoon.

Reliance on Cauvery can be tricky

Data shows that Cauvery is not quite a reliable water supply source. Of the eight years between 2011 and 2018, four were drought years. El-Niño has been showing up a lot more frequently than before. The other four years have shown irregular rainfall, with intense rainfall and floods in 2018.

This year, severe rains in the first half of August has rescued Bengaluru. But if Cauvery basin hadn’t received these rains, the city would have faced a severe water crisis.

The Cauvery Stage V project promises to take Bengaluru’s water supply to 2000 MLD, but it is expected to be completed only by 2023, in phases. By that time the demand for water would’ve gone further up, and the dependence on groundwater would not reduce.

So what’s the way forward?

Given that Bengaluru does not lie next to a ready source of water, like say Delhi or Kolkata, the solutions to our water needs keep coming back to the same old template of replenishing our lakes, rainwater harvesting (RWH) at a massive scale, and recharging the groundwater table. Add to that recycling of wastewater, and we might be able to achieve complete water self-sufficiency without needing to pull water from 100 km away.

The estimates vary, but they are all optimistic about how we can achieve self-reliance. For example, Arati Kumar-Rao writes in The National Geographic: “Bangalore gets between 800 and 900 millimeters of rain in a year, which is hardly a meager amount. If the city were to catch half of that, it would translate to more than 100 liters per capita per day, far more than adequate for domestic and drinking purposes.”

Water expert S Vishwanath points out that sewage treatment plants are being put in place in Bengaluru to treat 1440 MLD water. Once these begin to function, ‘fit for purpose’ water, cleaned of heavy metals but still rich in nutrients like phosphorus, can be returned to rural areas for use in agriculture. Vishwanath’s idea is to treat some of the wastewater further, to render it potable, and use it to recharge groundwater.

Some models even suggest an approach where the Cauvery supplies only half the requirement, at say 500 MLD, and the rest is locally sourced from RWH, recharged wells and recycled water. These models assume that the daily usage would be only around 100 litres per capita, since this is the standard requirement for a person. The assumption is that excess water use for washing cars, streets etc., can be reduced by premium pricing and lower availability.

Given that we already have a supply line from Cauvery, during the rain-deficit years in Bengaluru, we will still be able to fall back on the Cauvery to supplement our supply.

Despite all this optimism, the talk is predominantly of Day Zeros, construction bans, and city evacuations by 2022. All these alarms are justified given the direction we are currently headed in.

The only way forward is to get out of this dependence on an increasingly irregular source of water. Grandiose plans like bringing water from Linganamakki are just that – grandiose, and looking good on paper. As enough experts have pointed out, the water is here, in Bengaluru. And whether we can save it and tap it sustainably, will be the question that can answer all those grim warnings of Day Zero.

It may or may not ease water supply in Bangalore but sure to ease supplies to Tamil Nadu