It is a Sunday morning in December and I am at the entrance of Sanjay Gandhi National Park (SGNP), a protected forest located within the limits of Mumbai city. There are long queues of families who have turned up to enjoy the cool winter morning, stretching way beyond the entry gate of the park.

While I wait for Dinesh Barap — who belongs to the Warli tribe, indigenous to the forest — I can hear people, restless with excitement, talking about the journey ahead as they move forward in the queues to deposit the entry fee for exploring the park – INR 85 for an adult and INR 45 for a child.

Commonly accepted as Mumbai’s lungspace, SGNP is a 104 sq km forest. The park covers a sixth of Mumbai’s total land area — many times larger than New York’s Central Park or London’s Hyde Park.

The history of SGNP goes way back than its official christening in 1981 as the Sanjay Gandhi National Park. It used to be the Borivali National Park for a short duration from 1968, and before that, it was called Krishnagiri National Park.

“This was the basic raison d’être of the Krishnagiri National Park, the ancestor of the SGNP: guaranteeing access to drinking water for the growing city, with two lakes and dams constructed in forest by the British in the nineteenth century,” writes Frédéric Landy, a researcher at the French Institute of Pondicherry, in his paper on the human, non-human and spatial conflicts in the park. The lakes in question — Tulsi and Vihar — still supply water to the residents, but are no longer sufficient.

The park metamorphosed along with these titular changes; growing five times its initial area as surrounding areas were added to the original 20 square km ambit. It was only later that environmental protection concerns became a priority, as the threat to it materialised with growing suburbanisation. In 1996, a final notification cemented it as a “national” park.

SGNP boasts of a deciduous forest, 150 species of butterflies, 1,000 species of plants, forty species of mammals, 251 species of birds, nine species of amphibians, and a large variety of fish. It is these biodiversity concerns that reign supreme over the park today.

A forest that is a home

Meanwhile, Dinesh shows up and we set off on his bike, taking the longer route — the shorter one is blocked for visitors on Sundays. As we venture deeper inside the park, the number of people around us has thinned out. Only a few people on bicycles remain. The noise, diesel fumes and dust of the city are far behind us, even though it hasn’t been more than a 15-minute ride from the Western Express Highway, the main arterial road characterised by traffic.

For Dinesh, the park is home. He calls himself “moolnivasi,” native to the land.

“My mother tells me that we have been here for ten generations,” he says, using the Marathi word peedhi to describe his family’s connection to the land. We’ve arrived at a cluster of small houses around us each no more than two storeys tall, with sloping brick roofs. Some are built of brick and others of close-knit bamboo-like stems called karvy, and yet others of the wavy metal sheets, or patra, seen so often in the slums of the city.

This is Navapada, Dinesh announces, adding that it is an Adivasi padas or tribal hamlet home to approximately 180 families. It is one of the 42 padas (although some sources put the number of padas as low as 12 and as high as 47) in SGNP. Some slum dwellers too have link mingled with the Adivasis and set up their homes alongside.

The Dahisar River is a short walk away from Dinesh’s house. Along the way, the houses give way to enclosures — some rectangular, some round and some bigger than others — that are fenced by bands of tightly knit branches from the trees around the park and curtained with cloth strung between. These are called wadis, small plots used for vegetable and fruit cultivation which are far scaled-down versions of the farms of yesteryears.

“After the first rains, around the end of May,” explains Dinesh, “we dig a few small holes here, fill them with dried gobar (cattle dung) and leaves. We then burn it to make khad (fertilizer), after which we plant seeds.”

The Warlis use the seeds of the vegetables and fruits they’ve used over the generations. They grow cucumber, shirala (also called ghosala, turiya or ridge gourd), doodhi (bottle gourd), and pumpkin. Random fruit trees such as custard apple, jamun and mango can also be seen in the wadis. An additional sprinkling of nutrients for the soil comes in after 10 to 15 days, as they mix javla, a powder made of dried fish heads, in the soil.

The hard work of two months, Dinesh tells me, yields produce which they harvest for months together, using it for their own consumption; if some is left, it is sold within SGNP or the market near the Borivali railway station.

As the monsoon is a few months away, most of the wadis lie empty. But, Dinesh, along with his family, shows me one of his two wadis which has several rows of a variety of plants. “My brother has grown these,” he says, speaking with the fondness of the tomato, radish, onion, potato and custard apple plants.

Living on the banks of the Dahisar river, Dinesh tells me, is only natural as Warlis always settle near a river. It is where the water for growing the crops comes from, although the river has its ways of causing chaos too — flooding sometimes tears down the fences made of branches and washes the plants away.

At this time of the year, however, the river stays dry for the most part. The riverbed is clearly visible and only a few patches have small water pools.

But where there is a river, water is never far! Dinesh takes me to a small water hole near the bank of the river where the families of the pada collect groundwater. All we need, Dinesh says, is some digging to get water. “This water is good enough for us to drink, or use for washing clothes,” he says. “Deers, chickens, birds, all use this water.”

An ecosystem that inspires art

Being a Warli artist and the only artist from SGNP, the river means more than sustenance to Dinesh.

He has learnt the art from his grandmother who would paint murals for weddings, as is customary in their community. And while some elders who know this art form are still alive, their old age redirects most orders to him.

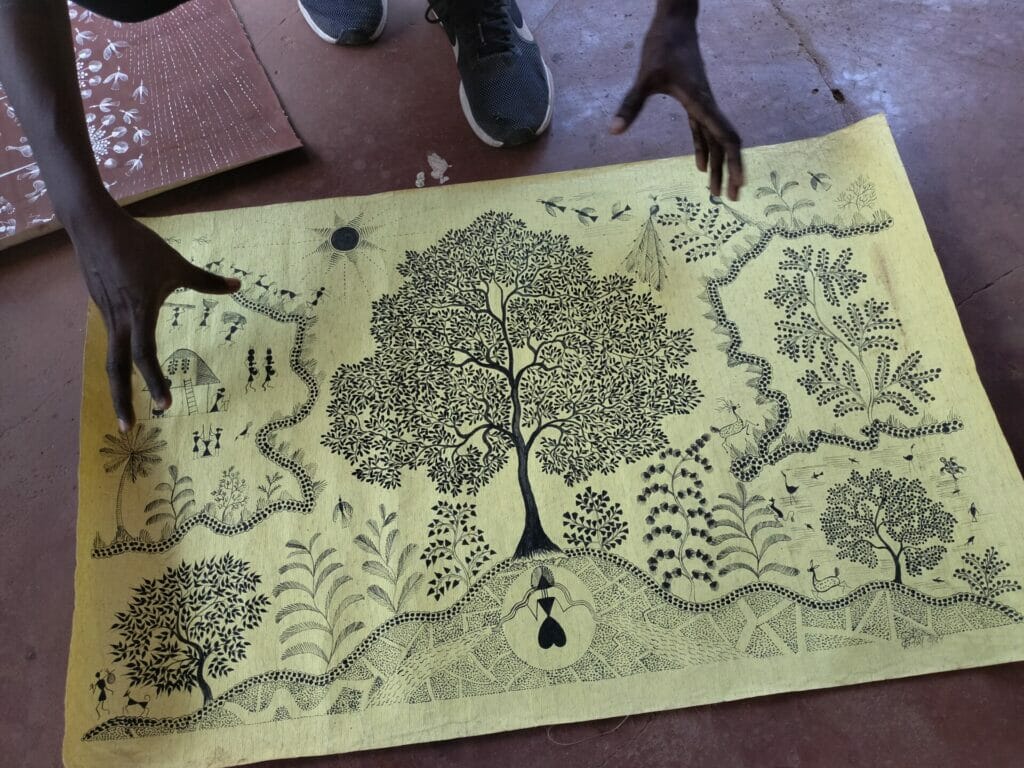

Warli art is known for its simplistic geometrical shapes to depict nature. The crops, animals, sun, houses, dances, musical instruments and togetherness are depicted in Warli art making it an important representative of the way of Warli life. One of Dinesh’s works in progress depicts the formation of a river with tributaries from across the landscapes joining at the centre — life thrives at its banks in the midst as vegetation, galloping deers, a lone tiger, the Adivasi’s huts, and men and women at work.

In another, a landscape, fish flutter through the stream that occupies the bottom layer. The sun sustains life at the surface, but their roots lie in water. Just as the Warli life built around the river is the subject of his art, the river is a vehicle for it. It provides the material, physically and metaphorically. To put it plainly, it supplies the paint.

Sitting by the side of a shallow pool of water, he rummages through the tiny rocks and stones at its banks and floor: picking, inspecting with deft hand, guided by some hidden knowledge. He then grates them against the surface of a larger rock, running each along a line, till it bleeds colour.

Using rocks as pigments comes with limitations of colour, but nature has no dearth of options for Dinesh. The chlorophyll in leaves supplies the green; flowers offer a variety; rice flour lends its starchy white; mango stains ochre. “I mix them with the gum from trees to make paint,” he says.

Over the years, Dinesh’s art has slowly gained popularity. The former and present Chief Ministers of the state are among those who have bought his artworks. His art features at the entrance of the SGNP, alongside the posters from the Jungle Book. Dinesh’s Instagram page welcomes orders from an international audience. He conducts the Dahisar River Walks along with Aslam Saiyad and invites people to get introduced to his art as well.

Dinesh is now carrying this tradition forward by teaching it to other Warli children. While we are talking, his niece comes along to show him a painting in progress. He gives her some feedback, asking her to add motifs to complete the sense of equilibrium that Warli painting depicts. “But not many are interested. Their interests lie elsewhere,” he tells me.

Forbidden waters of the SGNP

Not too far away from Dinesh’s home, in another hamlet by the Dahisar River, lives Devendra Thakur. He too is from the same tribe. An Adivasi leader of the Birsa Munda Adivasi Sangathan, his hamlet, Chinchpada, is home to 200 families.

Existence in his hamlet, however, is at a contrast as compared to Dinesh’s. “We are right next to the river,” he says, “but we’re not allowed to fish or farm. The Forest Department (FD) stops us from making wadis and growing fruits and vegetables, even though that is the bread and butter of our survival.”

This estrangement, Devendra explains, is particularly hard because the Warlis consider the river as their god. “The river is to us what a well is to a thirsty person,” he stresses.

Like Dinesh, Devendra also has a clear understanding of the Warlis’ historical association with the forest and the river. The Warlis, he says, have lived in the forest for generations. According to him, they had farms and collected wood to exchange it for food and fish in a barter system. But, after the establishment of SGNP, their traditional living style was impacted with the implementation of different laws.

It is not like the separation from nature has bought them development and prosperity. “We don’t have water. Aaj bhi khadda khod ke peete hai (Even today we drink water from the ground),” he says. “Women still go in the open for toilets, making them vulnerable to creeps. We have no electricity or good roads.”

Read more: The story of Aarey forest under three governments

‘Natural allies not enemies’

The disparity between Dinesh’s and Devendra’s hamlets is explained by the laws of the land that have accumulated with the burgeoning national importance of the park. “All the land in the SGNP is reserved forest declared under the Indian Forest Act, 1927,” says Sunil Limaye, former director of the SGNP and chief conservator of forest (wildlife). “The Adivasis are encroachers, so they have no rights.”

But, the Adivasis strongly oppose to such characterisation. “[We are] the natural allies of the forest and not its enemies.” This is how one Adivasi (Warli) petitioner, Manik Rama Sapte, with the backing of other social organisations, described the Warli Adivasis in Court in 2000.

The Adivasis constantly live under the fear that they will be evicted from SGNP after environmental activism was taken to SGNP with some organisations going to the court against the slum dwellers who had set up homes in the park. A 1997 High Court ruling permitted the demolition of all homes settled in the vicinity of the park after 1995. The Adivasis were caught in this mix.

Sapte’s petition, recounts Ramya Ramanath in her book A Place to Call Home, claimed the Warlis had lived in the park for 500 years, with 2,500 families having domicile. “The High Court’s response to the petition, issued in 2003, acknowledged that Adivasis, unlike ‘slum dwellers, unauthorised occupants and trespassers’, were ‘wedded to [the] forest and they preserve, protect and propagate [the] forest’, but judged the petitioners’ assertion of 2,500 such families to be ‘falsified’ and a ‘tall claim’,” she writes and adds, “In the court’s analysis, no more than 260 such families lived there and they had no more legal right over the forestland than other slum dwellers required to meet the requirements for eligibility and relocation.”

The Court case also recounts a footnote that plays heavily in Limaye’s characterising the Adivasis as “encroachers.” Both claim the padas were “relocated in tribal area village Khutal of Palghar Taluka in Thane district for which the government incurred substantial expenditure.” In spite of giving land to them, most of them came back, says Limaye.

If Devendra represents a tipping point for the Adivasi’s rights, Manisha Dhinde offers a glimpse of a radically different present.

Manisha lives in Maroshi pada, one of the 27 Adivasi padas in the neighbouring Aarey Colony. Her family owns three acres of land they use for farming all year round.

“We grow rice in the monsoon that we store for the whole year. After harvesting, we switch to urad dal, as it doesn’t require that much water and needs more sun,” explains Manisha. In a separate portion, they grow vegetables and fruits: bhindi, karela, dudhi, ambadi, papaya, and more. The vegetables have obvious differences from the ones available in the bazaars: cucumbers the size of arms, plump red and green bhindi, ice apples like coconuts, a single pumpkin weighing four to five kgs.

It is a testament to the fertility of the land. “My forefathers would only grow food needed for their own consumption. But now in a single week, we’re harvesting eight kgs of bhindi and four kgs of karela. We can’t eat all of that in one go.” In recent years, with the help of the NGO Earth Forever, which introduced natural fertilisers and manure, her yield has grown so much that she has started selling excess produce in the market and online.

If you ask her where she gets the water needed for farming, the answer will sound familiar. “Because Maroshi pada is so close to the Mithi nadi (river), we always have water available. All we need to do is dig a hole five-feet-deep, and we’re set for the whole year,” she says. The proximity to the river also allows the pada residents to enjoy fishing.

As the Aarey Colony land was transferred to the Dairy Development Department in the 1960s, it has been able to escape the strict regulation imposed on SGNP. But this has not been without its downsides. What used to be forest land stretched across 3,000 acres has whittled down to 1,300, parcels of land parsed out to public housing projects, industrial parks, state reserve police force complex, a crematorium and more recently, a metro car shed.

An impending exit from the park

This period of relatively fewer restrictions and kinship with the forest and rivers might be coming to an end, as 812 acres of the adjacent Aarey Colony were declared “reserved forest” in 2020, a fate similar to that which befell the Adivasis of the SGNP in the 1970s. The land was handed over to the state’s Forest Department, with eventual plans of it joining SGNP.

Lip service was paid to protect any tribal rights affected in this move, say the Warlis. In any case, the invoked Indian Forest Act, 1927 necessitates that the government appoints a forest settlement officer (FSO) to survey the demarcated area and inquire into any claims of rights over the land and forest produce.

In August 2022, several Adivasi padas in Aarey complained that forest officials were destroying their ready-to-harvest fields in the quiet of the night, stopping them from any further cultivation and harassing them to leave. Three months ago, ten hectares of farmland was cleared “in a heavy-handed manner” with over 300 police personnel, the FD claiming encroachment by the Adivasis over the pandemic.

Sunil echoes this claim, vociferously, “The residents of Sai Bangoda and other padas clear the forest area and form wadis in its place. That is not allowed.”

The Warlis, on the other hand, claim the FD is trigger-happy when it comes to introducing new rules. Manisha says the latest is that fishing is not allowed in the Tulsi lake, though many fishermen still do so, taking the risk of a possible FIR.

The threat of relocation is ever present among the Adivasis. Just last month, around 2,000 Adivasis from 200 padas across Mumbai and Palghar protested the deforestation and displacement pinching on their rights.

If the Forest Department is anything to go by, relocation is inevitable. “The Court has categorically said that the Adivasis staying in SGNP are encroachers, and should be removed. But because the state is a welfare state, it has decided they will be rehabilitated not too far away,” says Sunil. “The government will take into consideration their lifestyle, but they are not like typical Adivasis. They are semi-urbanised, using electricity, TV and vehicles. They are not solely dependent on the forest.”

The Warlis are in opposition to their relocation. “How will we live in buildings? So much of our culture and traditions are tied to the jungle and river,” argues Dinesh. “We do not want rehabilitation. We want to stay where we are,” echoes Manisha.

But perhaps because of the relatively poor material conditions in Thakur’s pada, it looks like he might be among those who might compromise. “We do not want to move out of here,” he says. “But if we are going to be shifted, move us nearby. We need houses on open land, not buildings of 550 square feet, because that is what we’re used to.” Thakur refers to the three crore rupees compensation and 90 acres of land for relocation of Warlis and slum dwellers in Aarey, asserting that this proposal was once floated, but never implemented.

“The government wants to rehabilitate them properly as soon as possible,” adds Sunil. “But getting suitable land” — which he insists will include some space for plantation and cattle — “and getting the Adivasis to accept it is very difficult.” The search is still going on.

This story was produced with support from Internews’ Earth Journalism Network.