The constitutional right to vote has been the cornerstone of India’s democratic foundation. In a country as diverse, with 900 million registered voters in 2019 as per Election Commission figures, the model for exercising universal adult franchise has often been applauded. But the model remains beset with a set of unique challenges. One such long-standing challenge is checking duplicate entries in the country’s electoral rolls. To address this issue, the union government has now proposed linking of the Aadhaar and the voter ID, as represented by the Electoral Photo Identity Card (EPIC).

The proposal immediately evoked strong criticism and raised serious questions over the constitutional principles of universal suffrage, right to privacy and citizenship. And though the government continues to affirm that linking Aadhaar to Voter ID remains optional, there are plenty of reasons to be cautions of this new policy.

Background

Parliament passed the Election Laws (Amendment) Bill 2021 to amend the Representation of Peoples Act 1950 and 1951. The amendment was passed in lieu of the proposal of election reforms that have long been pending.

The Election Commission of India (ECI) had, for the first time in 2015, proposed a slew of reforms which included cleaning of the country’s electoral roll among many other recommendations.

The ECI proposed a rollout of a National Electoral Roll Purification and Authentication Programme (NERPAP) to delete duplicate entries from the electoral rolls. The programme focussed on linking Aadhaar to Voter ID in order to detect and delete fake entries. However, the programme was shut down the same year, as the Supreme Court unequivocally held that Aadhaar is a voluntary scheme and cannot be made mandatory.

In April 2021, ECI once again asked the union law ministry to expedite the work on pending election reforms. In November 2021, the law ministry informed that a cabinet note on election reforms had finally been passed by the Prime Minister’s Office (PMO).

Read more: Why thousands of Bengalureans could not vote this Lok Sabha election

Before introducing the NERPAP, the ECI initiated a pilot on linking Aadhaar and Voter ID in two districts of Nizamabad and Hyderabad in 2014 (then in Andhra Pradesh). The state governments used applications from the State Resident Data Hub (SRDH) to clean the electoral rolls. The SRDH uses data on state residents, which is supplied by the Unique Identification Authority of India (UIDAI).

The SRDH was created by UIDAI to collect information on state residents, similar to what Aadhaar does but without biometrics. Today SRDH is being managed by private players and is a part of a larger state surveillance system.

But the final electoral rolls published using SRDH, which did away with the door-to-door identification process, found activist groups claiming that around 55 lakh voters had been arbitrarily disenfranchised in Andhra Pradesh and Telangana.

The major concerns

Following are some of the key concerns raised by civil society on linking of Aadhaar and EPIC:

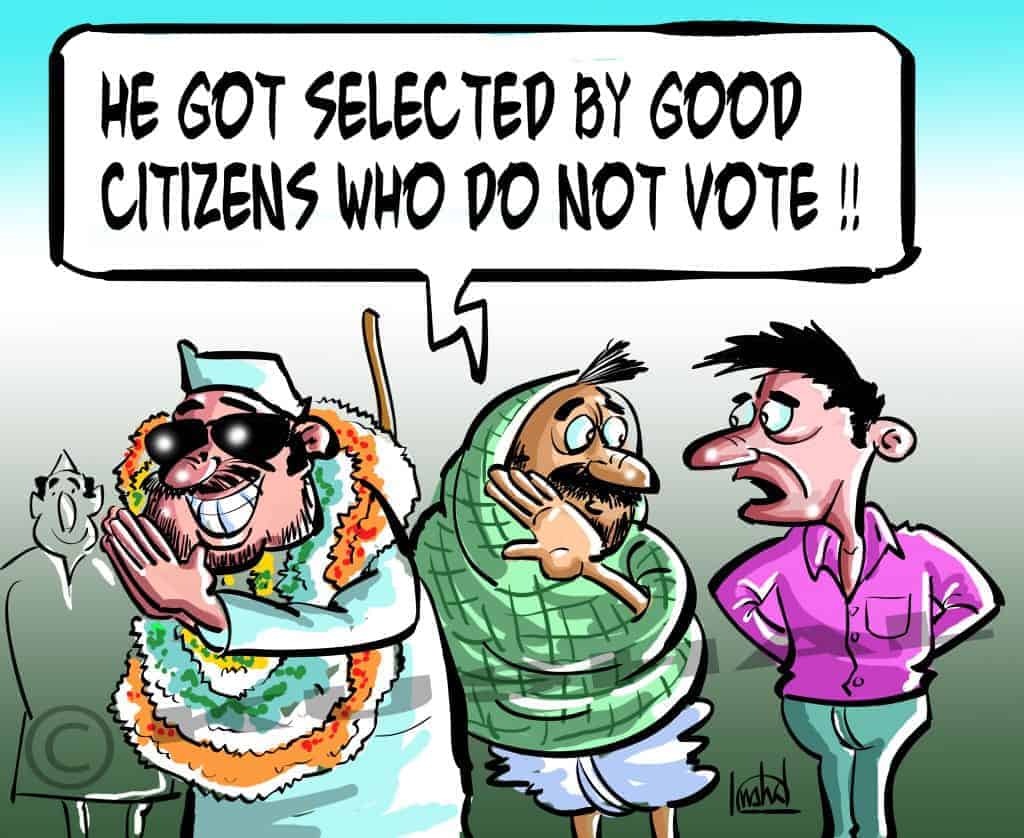

1. Mass disenfranchisement: Experts and activists fear that after initial lessons from Andhra Pradesh and Telangana, the move can trigger mass disenfranchisement barring citizens from exercising their constitutional right of voting.

2. Right To Privacy: The linkage of Aadhaar and Voter ID endangers a crucial constitutional freedom, the right to privacy. The linkage allows the state access to all demographic information of the voter. This could be used for voter profiling, undermining voters’ right to privacy and voting secrecy.

3. Increased voter fraud: Critics say the government’s line of thought that Aadhaar can be used to check bogus entries in the electoral roll is fundamentally flawed. According to anti-Aadhaar campaign group Rethink Aadhaar, self-reported errors in Aadhar database are 1.5 times higher than errors reported in the electoral data records.

4. Proof of residence: Primarily, Aadhaar is just a proof of residence and not of citizenship. Voting right is only granted to citizens and not to residents. Hence linkage of Aadhaar to Voter ID infringes the citizens’ constitutional right to vote.

5. No voluntary option: Despite the government’s persistent focus on keeping this process of linkage optional, in practice the use of Aadhaar has been mandated for most of the state’s welfare policies. From the opening of a bank account to delivery of LPG, Aadhaar remains mandatory for access to basic services. This is despite an SC order stating that the use of Aadhaar cannot be mandated, but can only be voluntary.

Government’s stance

The union law minister has failed to provide satisfactory replies to these queries raised in Parliament. The government says that the move will ensure cleaning of the electoral rolls, which remains the topmost priority in terms of election reforms.

On right to privacy, the government has responded that the bill passes the test for privacy laid down in the famous case of KS Puttuswamy v. Union of India (see box below), thereby ensuring that the move remains within the constitutional limits of upholding the privacy of the voter.

But the various other concerns raised by the opposition in both the houses, have remained unanswered.

Proportionality test as laid down in the famous Puttuswamy case

The landmark judgment held that right to privacy is a fundamental right and any sanction against such right must be:

- Authorised by the law.

- Proposed sanction must be necessary in a democratic society for a legitimate aim

- Extent of such interference must be proportionate to the need of such interference

- There must be procedural guarantees against abuse of such interference