The usual suspects blamed for plastic pollution are littering, slums and a dysfunctional garbage collection system. But contrary to popular belief, even when waste makes it to landfills, it’s not all that secure. Pollution from landfills accounts for 45% of the plastic – a whopping 4.1 million metric tonnes in 2015 – lost in the environment.

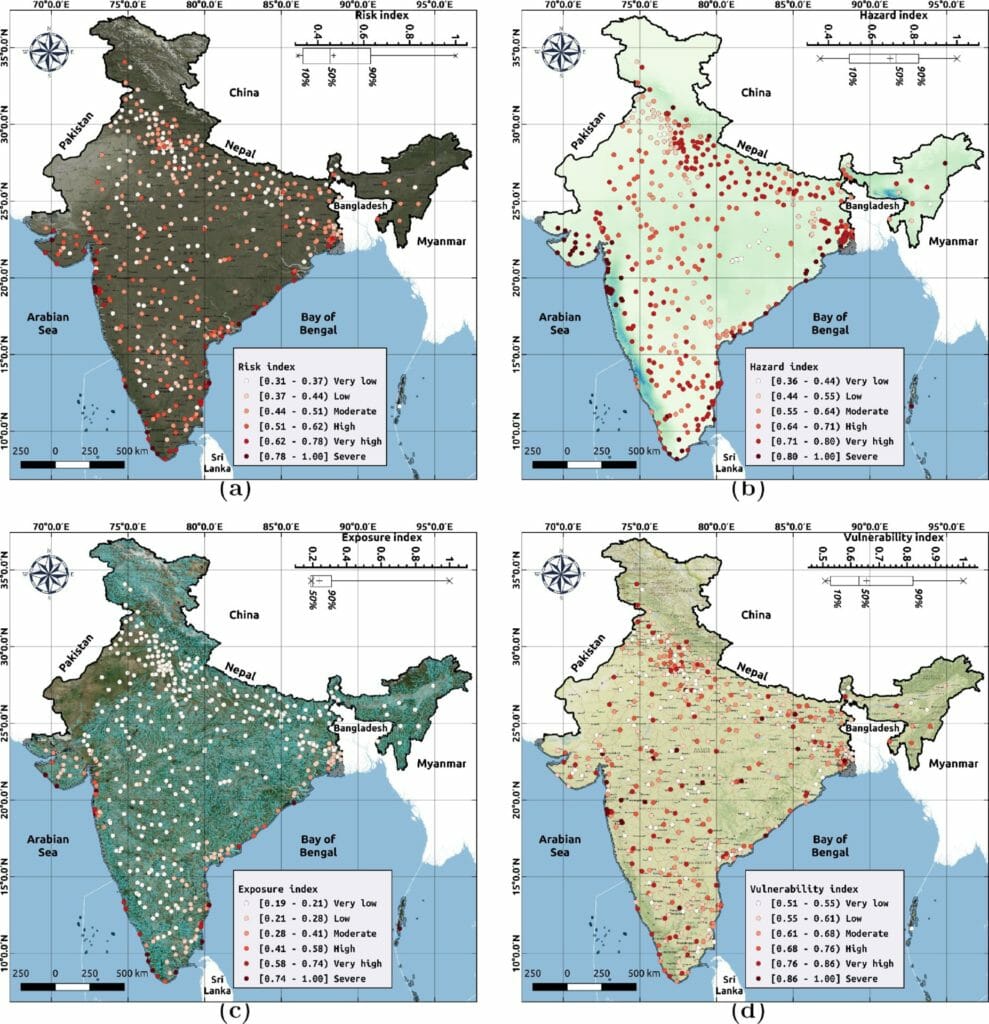

Mumbai’s landfills are terrible offenders. A recent study, titled ‘Risk of plastics losses to the environment from Indian landfills’, and published in the Elsevier Journal Resources, Conservation and Recycling assessed the risk of plastic pollution posed by landfills in 496 urban Indian cities.

Mumbai topped the charts. It took the lead of the 18 cities that pose a severe risk of plastic losses – increasing the likelihood of plastic escaping to the environment, and from the ecosystem into the food chain.

“The major contributor of plastics in the environment is mismanaged waste, which comes predominantly from open dumps,” says Vinay Yadav, lead author of the study and assistant professor at the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT), Kharagpur.

Climatic factors

So what makes the risk of pollution from landfills in Mumbai so severe?

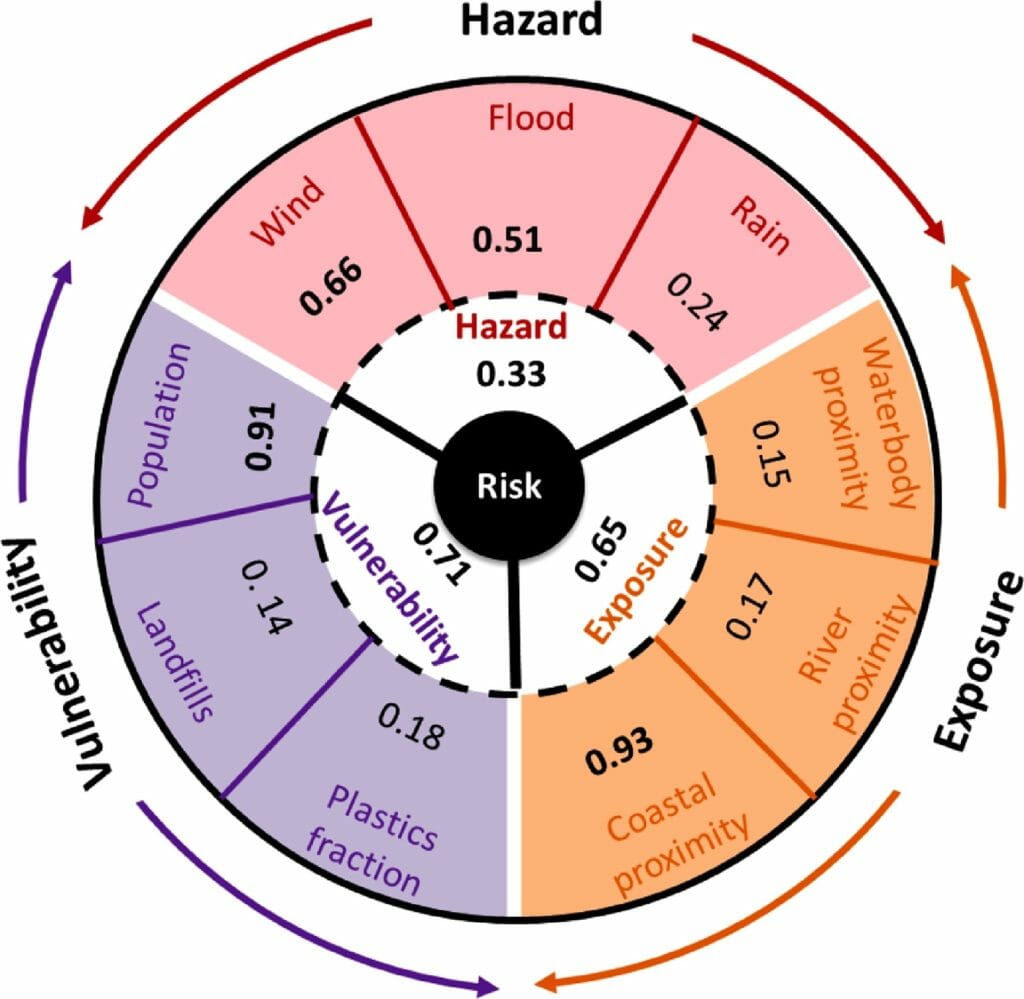

Mumbai is a triple threat, scoring high on hazard, exposure and vulnerability. This is due to a mix of climatic and manmade factors, making it likelier for plastics to escape from the landfill and end up in the environment.

“Plastics from landfills enter the environment through various pathways, namely via the influences of wind blowing, precipitation and runoff, flooding, and the intervention of stray animals and humans,” reads the study. Climatic factors make up most of the hazards to a landfill, especially in a coastal city like Mumbai.

Human and animal interference, from stray dogs and waste pickers who expose lighter plastics to the hazards, play only a minimal role at this stage. Yet differently, the location of the landfills determines the amount of havoc the risks can cause. Proximity to a water body means plastic pollution is reaching the marine environment quickly, thus entering the food chain in a quick hop, skip and jump.

To Mumbai’s disfavour, all three of Mumbai’s landfills – Mulund, Deonar and Kanjurmarg – are close to the sea.

Mumbai’s landfills

This leaves vulnerability, which is the product of the population, the number and condition of landfills and the share of plastics in municipal solid waste (MSW).

Mumbai’s 12 million population speaks for itself. In the data used by a study from 2016, Mumbai was generating 10,000 tonnes of waste every day. The fraction of plastic waste was 8% by weight and 20% by volume. “We have a low per capita generation of plastic waste compared to developed countries. But since overall waste generation is high, plastic waste is also high,” says Vinay.

Yet another factor that leads to more plastic pollution than in developed countries is the condition of the landfills.

“In India, we mainly have unscientific landfills, also called dumpsites,” says Richa Singh, deputy programme manager of the MSW team at the Centre for Science and Environment (CSE), a non-profit research organisation.

Of the three landfills in Mumbai, the almost century-old Deonar and closed Mulund are unscientific. “These are not provided with any protective mechanisms to minimize the pollution due to waste,” says Richa, referring to a base layer to absorb impurities and protect the ground, vertical wells to capture methane and other gasses emitted, fencing, etc. Only Kanjurmarg is a scientific landfill with a bio-reactor for biodegradable waste, although Vinay adds it lacks fencing.

Pic: Elsevier Journal/CC BY-NC 4.0

Harms of plastic pollution

Such rampant plastic pollution bodes serious harm to the ecosystem and marine life, and ultimately, human health.

“Plastics break down into microplastics, of sizes less than five millimetres, in landfills,” explains Vinay. “When it rains, they mix with the thick leachate that collects, seeping out and contaminating groundwater.” The chemicals in this contaminated groundwater can cause irreversible damage to human health, says Richa.

In coastal cities, marine animals feed on plastic which is then consumed by humans, indirectly consuming plastic. But these harms are not contained locally; they spread far and wide. Vinay brings up a 2021 study that found plastics in salt from Gujurat and Tamil Nadu, both major producers of salt.

Solutions

To reduce the pollution from landfills – not restricted to plastic – both Vinay and Richa bring up reducing the dependence on plastic and landfills.

The Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC) can claim improvement in this regard; the amount of waste collected has reduced from over 10,000 tonnes to 6,300-6,500 tonnes in 2022. Waste segregation rules and the state-wide and central ban on single-use plastic are in place, although implementation is weak. The BMC is also in the process of closing the Deonar landfill by building a waste-to-energy plant at the site, another method also notorious for causing pollution.

“Anything which can be composted, recycled and recovered should not be disposed of in the landfills,” says Richa, backed by the Solid Waste Management Rules, 2016. “Only the inerts, street sweepings and drain silt should be landfilled.”

When it comes to improving the landfills currently present in Mumbai, Vinay recommends fencing the landfill at Kanjurmarg, which would stop microplastics from leaching out into the environment.

Read more: Explainer: Segregating waste manually to minimise the burden on landfills

Landfill laws

The rules, however, go even further.

“As per the Swachh Bharat Mission 2.0 operational guidelines,” says Richa, “all legacy waste dumpsites (containing mixed waste including plastics) need to be reclaimed by 31st March 2024. The legacy plastics reclaimed from landfills should be disposed of in an environmentally sustainable manner. They can be used in road construction or cement kilns co-processing units as an alternative fuel and secondary raw material,” says Richa.

Only the waste which cannot be treated should be disposed of in landfills, constructed and operated scientifically to minimise pollution into the environment. The CPCB norms for such a landfill include, says Richa, “a barrier layer (high-density polyethene layer), leachate collection and treatment system, and a landfill gas collection and treatment system.”

The share of plastics in MSW is expected to increase by 266% by 2014. All signs point to plastic pollution increasing, adding to the burden already faced by cities and upgrading the risk level of other cities. A proper waste management and disposal system has never been more important.