Even when the howling wind and torrential rain brought by Cyclone Amphan was causing havoc around her on May 20, Sabita Sardar was not afraid. “We are used to dealing with bad weather. I wasn’t feeling scared. In fact, those who live in concrete homes were more scared,” she said.

For 40 years now, Sabita has been living on the streets of Gariahat, a popular market area in south Kolkata.

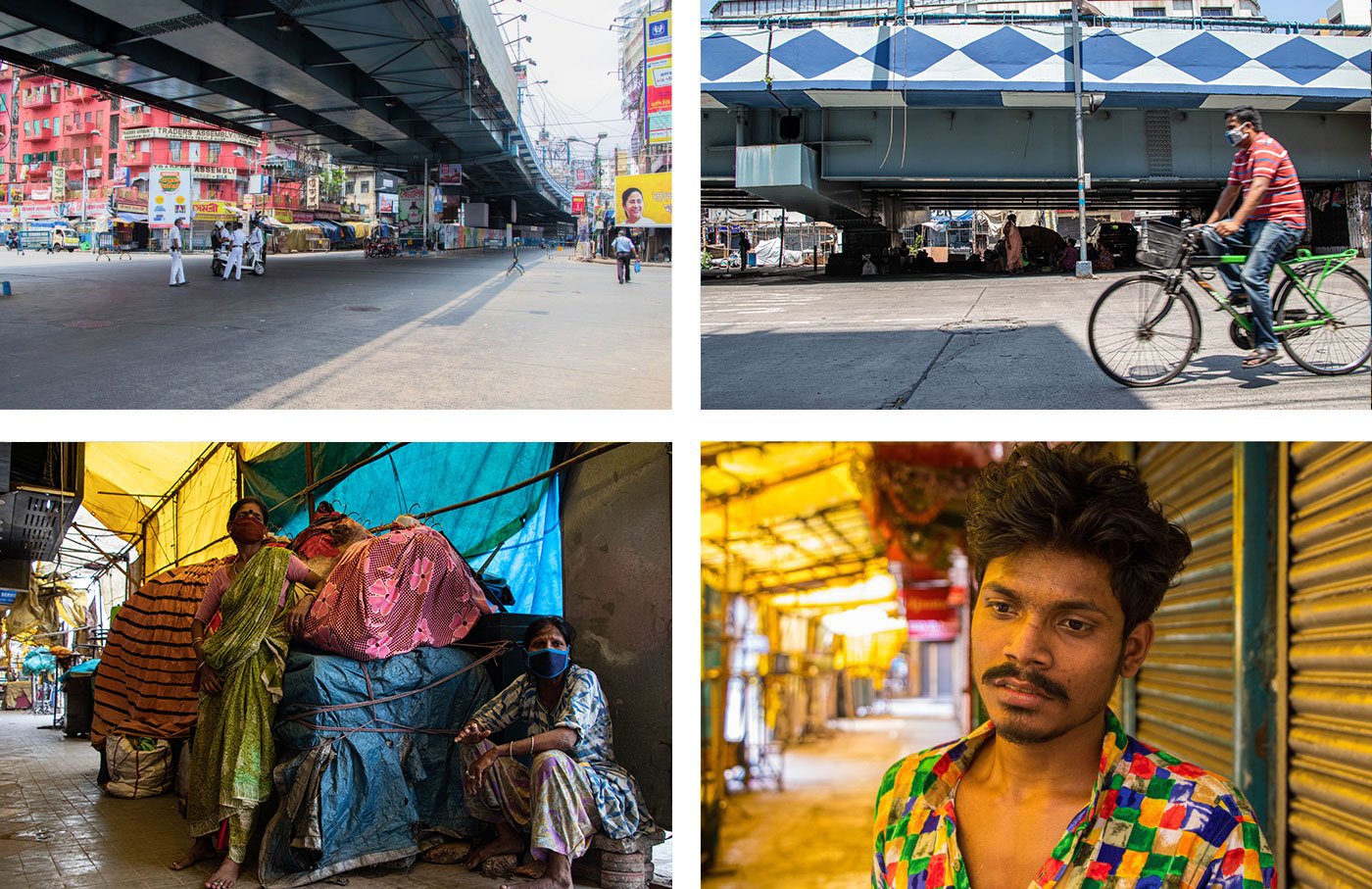

That day, when the super cyclonic storm passed through West Bengal’s capital city, Sabita and a few other homeless women sat huddled together in her tricycle cart under the Gariahat flyover. They spent the night like that. “We sat there while loose glass pieces flew around and trees fell. We got wet as the winds blew the rain towards us. We heard loud doom daam noises,” recalled Sabita.

She had returned to her spot under the flyover just the previous day. “I came back to Gariahat from my son’s house a day before Amphan. My utensils and clothes were lying scattered, as if someone has dug through them,” said Sabita, who is around 47 years old. She had walked back four kilometres from her son Raju Sardar’s rented room in the Jhaldar Math slum colony in Tollygunge, where Raju, 27, his wife Rupa, 25, their young children, and Rupa’s younger sister live.

She had gone to Jhaldar Math after leaving the shelter where Kolkata Police had taken Gariahat’s pavement residents on March 25, once the lockdown began. That night, police officials had approached Sabita and the others living under the flyover. “They told us we can’t stay on the streets due to the [corona] virus, and that we have to move to a shelter for now,” she said. They were taken to a community hall of Kolkata Municipal Corporation’s ward number 85.

On April 20, a month before Amphan, I saw Sabita seated on a rickety wooden bench on a deserted footpath in Gariahat. She had left the shelter on April 15 and was staying with her son, but had come to check on her belongings. The makeshift stalls where hawkers usually retail their goods, remained folded for the lockdown. Only a few of the people who live on the pavement were around. “I came to check on my clothes and utensils. I was anxious about them being stolen, but was relieved to see that everything was intact,” she said.

“We were not okay in the shelter,” Sabita added. At the community hall that temporarily housed around 100 people, she said, “Fights would erupt if someone got more food than the others. This happened daily. There were physical fights over an extra scoop of rice.” And, she added, the quality of the food began to deteriorate. “My throat burned from the spicy food. We were given the same meal of poori and aloo day after day.” It was a hostile environment – beside the food fights, the guards were abusive, and the people staying there were not provided adequate drinking water or soap for washing.

The footpaths of Gariahat have been Sabita’s home since she was seven years old, when she came to the city with her mother, Kanon Halder, and three sisters and three brothers. “My father used to travel for work. Once, he went for a job and never came back. “So Kanon and her seven children boarded a train from a village (Sabita doesn’t remember the name) in West Bengal’s South 24 Parganas district to Ballygunge station in Kolkata. “My mother worked as a daily wage labourer on construction sites. Now she is too old for that. She picks waste or begs for money,” Sabita said.

Sabita too started picking waste (to sort and sell to scrap dealers) as a teenager to support her family. In her late teens, she married Shibu Sardar, who was a street dweller too. They had five children together, including Raju. Shibu worked in the Gariahat market hauling produce for shops and cutting fish. He died in 2019 due to tuberculosis. Now their two younger daughters and son live in residential schools in the city, run by NGOs. Their older daughter, Mampi, 20, and her infant son live with Sabita most of the time, away from Mampi’s abusive husband.

When the Gariahat flyover was built in 2002, many including Sabita and her extended family – mother Kanon, a brother, a sister, their children and spouses – shifted from the open pavements to under the flyover. They lived there until their lives were disrupted by the Covid-19 pandemic.

On March 25, Sabita, Kanon, Mampi and her son, along with Sabita’s brother, sister-in-law Pinky Halder and their teenaged daughters were all taken to the shelter. A few days later, Pinky and her daughters were released at the request of her employer. Pinky worked as a domestic worker in Gariahat’s Ekdalia neighbourhood. One of her elderly employers was finding it difficult to cope with the household chores. “She filed an application in Gariahat police station, and they released us after she [the employer] gave them a written undertaking that she will take responsibility for us and look after us,” said Pinky.

Pinky returned to fetch her mother-in-law, Kanon, from the shelter on April 15. “She was not able to cope in that hostile place,” she says. But when she reached the shelter, Pinky got into an altercation with the doorman, who insisted on permission from the police station. “I only asked him if he demanded to see signed permissions from everyone. This enraged him, and he called the police. As I waited for my mother-in-law, a policeman showed up and started hitting me with his cane,” she alleged.

Kanon and Sabita left the shelter that day. Sabita went to her spot under the Gariahat flyover, and her mother was sent to live with Sabita’s sister in Mallikpur town, about 40 kilometres away, in South 24 Parganas.

Sabita used to earn Rs. 250-300 every week before the lockdown, but could not get back to her work of collecting scrap after leaving the shelter, because the shops buying scrap materials were not open for business. And those who left the shelter had to hide from the police and their lathis. So Sabita went to live with her son’s family in Jhaldar Math.

Usha Dolui, also a waste worker in Gariahat, said, “I have been evading the police. I do not want to be beaten or catch the virus. If the food had improved, I would go back to the shelter.” A widow, Usha got out of the shelter to collect food and rations distributed by NGOs and citizens for her teenaged son and daughter, whom she had left behind in the community hall.

Only 17 of Gariahat’s pavement residents remained at the shelter when they were all asked to leave on June 3. A cleaner at the community hall told me that many ran away under the pretext of getting drinking water from a nearby tubewell.

Usha too has gone back to her original patch under the flyover, across the road from the Gariahat police station. Twice, she says, a policeman came and kicked their pots over when they were cooking. He confiscated the dry rations distributed by some people. He has also taken away her tricycle cart, on which she stored clothes and bedding. “He told us to go back to our homes, wherever we came from. We told him that if we had homes we wouldn’t be living on the streets,” said Usha.

Sabita came back to live in Gariahat before Amphan struck because her son Raju was struggling to feed six family members. He used to work as a salesman at a shoe shop in Gariahat, earning Rs. 200 a day. After the lockdown he has tried hard to conserve money. He cycles to a market seven kilometres away to buy vegetables at a cheap rate. “We received some ration from my son’s school [contributed by teachers] and have been eating boiled rice and potato for days now,” Raju said. “We need biscuits, tea, milk, cooking oil, spices, and diapers for my two-year-old. I am worried if I need to buy something suddenly, what will I do? I do not have any more cash money left,” he said.

Sabita has rented out her tricycle cart to a fruit seller who was supposed to pay her Rs. 70 every day, but gives her only Rs. 50. “We have to eat,” she said. Mampi and her eight-month-old son are with Sabita these days. The money is not enough to feed them all, and they need some of it to pay to use the nearby Sulabh bathroom.

Over the last few days, Sabita has started to collect scrap paper because some shops are now buying it. She gets Rs. 100-150 for three sacks.

Living on the streets with all its dangers and risks has made Sabita fearless about pandemics and cyclones. “People can die anytime – even while walking on the streets they can be hit by a car. The flyover has saved us,” she said. “The morning after the storm, I ate panta bhaat [leftover rice]. Once the storm was over, things became normal.”

[This article was originally published in the People’s Archive of Rural India on June 18, 2020.]