Researchers at Paani.Earth have documented firsthand evidence exposing the inadequate wastewater treatment in five Bengaluru sewage treatment plants (STPs). This untreated water is making its way to drought-prone areas in Kolar and Chikkaballapura.

In part one of this series, we will examine the KC Valley Project, its acclaimed wastewater management methods, and evaluate its actual effectiveness in comparison to Paani.Earth’s research.

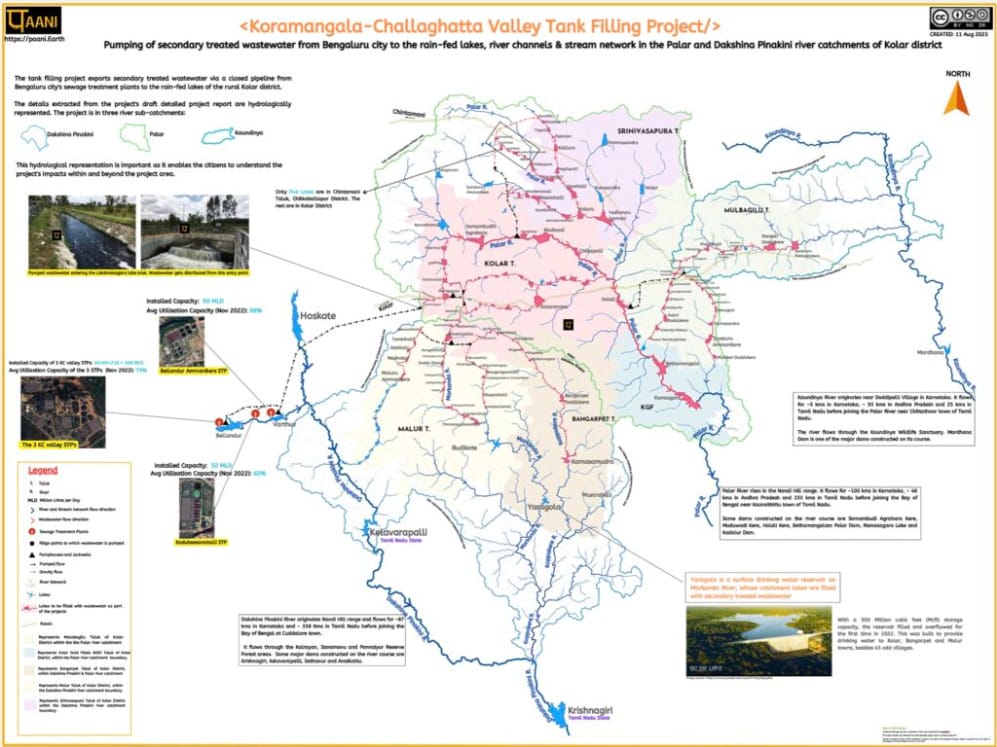

The Koramangala Challaghatta (KC) Valley project was launched by the Karnataka government in 2018. It was meant to treat 440 million litres of sewage water from Bengaluru’s five STPs, everyday, to recharge ground water in the drought-prone areas of Kolar and Chikkaballapura. The execution of the project cost Rs. 1,342 crores and is considered as one of the model projects for wastewater management in the state.

As reported by The Hindu, Kolar struggles to sustain itself due to the depletion of groundwater, so borewells were dug to depths of 2,000- 2,500 feet. Since agriculture is the primary occupation of the district, the lack of water resources has impacted livelihoods.

While initially intended for reusing treated Bengaluru wastewater for irrigation without affecting drinking water, the KC Valley Project eventually primarily served as a groundwater recharge initiative. This approach not only involves utilising water for irrigation facilities, but also affects the quality and availability of drinking water in the region.

Treated water monitoring primary responsibility of KSPCB

The Indian Institute of Science (IISc) Bengaluru, has conducted some assessment studies on the project during the initial stages. They gave a statement that continuous monitoring for this project is essential and that IISc would take care of it. However, there have been no public records available on the quality of the treated water, either from IISc or the Karnataka Pollution Control Board (KSPCB), whose main responsibility is to monitor and evaluate this project.

“IISc conducts project-wise monitoring, but the primary responsibility lies with the KSPCB, the only entity capable of continuous treated water monitoring. However so far, only newspaper articles have revealed that the water quality is not up to the mark, but not a single report or data set has been released by either IISc or KSPCB,” says Nirmala Gowda, co-founder of Paani.Earth.

Read more: Bengaluru’s treated water foaming in Kolar: Plan to use in irrigation on hold

Litigation filed

When the farmers started complaining about dirty water reaching their tanks, a Public Interest Litigation (PIL) was filed in 2018 to demand testing the contamination levels and the presence of heavy metals in the treated water. A study conducted by IISc showed that the quality of the treated water was in accordance with the standards set by the KSPCB and the Supreme Court permitted the flow of the water to these tanks.

There have been several news reports on the questionable status of the quality of treated water. However, despite litigation and media reports, the endeavours to implement tertiary treatment, a crucial aspect that appears to have been neglected by both the study reports and the government, failed to receive enough attention.

Inefficient and non-transparent practices

It is in the jurisdiction of KSPCB to monitor and evaluate the treated water from the five STPs. As per Paani.Earth’s report, “The monitoring would provide insight into the risks of the project and would also provide necessary corrective and remedial measures to mitigate the risk of pollution. This monitoring process starts before the project’s implementation when the baseline data is established.”

“As part of the water quality monitoring plan, water quality goals are set for the water bodies, and repeated observations covering different seasons are made. The water quality monitoring plan can include real-time monitoring of wastewater, discharge points and lakes receiving secondary treated wastewater. It can also include investigations into the threat of emerging contaminants by engaging research institutes.”

“In addition to the physio-chemical & bacterial parameters, an assessment of biological parameters, including biological indices & trophic status, can provide a more comprehensive status of the water bodies receiving secondary treated wastewater. All this data is compiled and compared to the water quality goals. This comparison would lead to identifying gaps in water quality and help identify the nature and magnitude of pollution control needed.”

However, Paani.Earth claims that none of this is being done by the KSPCB and they are only monitoring three lakes out of the 122 lakes that are a part of the project. These three lakes, though, were already being monitored prior to the project and is independent of the analysis in relation to the project. The three lakes are: Narsapura, Mulbagilu and Huldenahalli.

Bengaluru Water Supply and Sewerage Board (BWSSB) operates all five STPs from where the treated water makes it way to Kolar and other regions. As per directions from the KSPCB, BWSSB has a portal that measures the parameters of the treated water on a continuous basis.

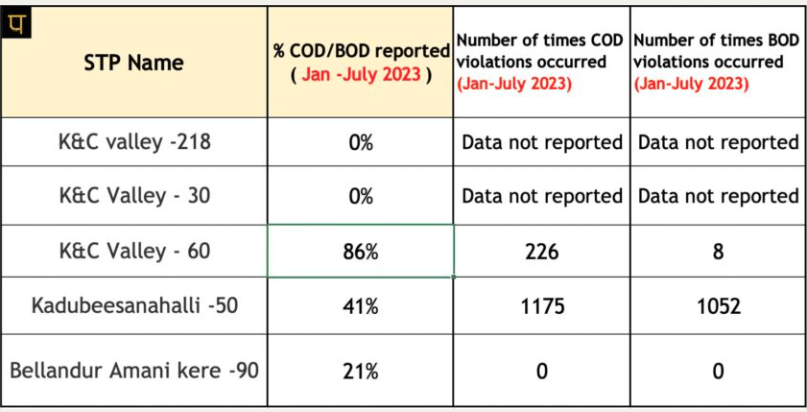

Paani.Earth scraped the data on an hourly basis for all the five STPs from January 1, 2023 to July 31, 2023 for two wastewater parameters: Biological Oxygen Demand (BOD) and Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD).

As per their analysis, two STPs, namely KC valley-218 and KC valley-30 did not report any data. Kadubeesanahalli-50 STP reported only 41% of the time, and Bellandur Ammani Kere -90 STP reported only 21% of the time.

KC valley-60 STP fared better, with 86% reporting. This reflects lack of transparency as the data is not updated on a continuous basis, which is what the portal is for. While also measuring the number of times COD and BOD were violated beyond the mentioned parameters, Paani.Earth found that in two STPs, KC Valley-60 and Kadubeesanahalli-50, COD levels were violated 226 times and 1,175 times, respectively, and BOD levels were violated 8 times and 1,052 times. Bellandur Ammani Kere -90 STP did not reflect any violations. The violation data for the remaining two STPs could not be recorded since they did not report any data.

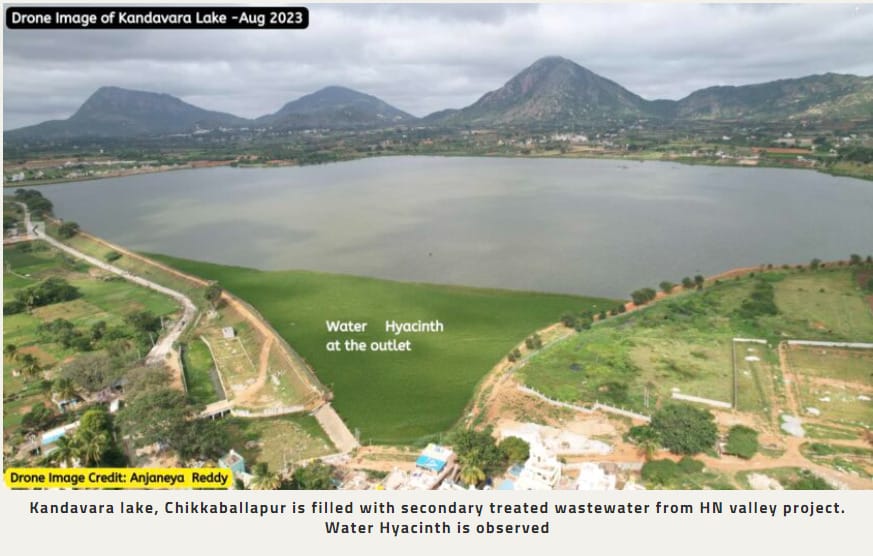

There is a growing need for tertiary treatment of sewage water because this process removes phosphates. While phosphates are an essential element for plant life, excess quantities of it leads to eutrophication, posing a threat to marine life in lakes. However, when the primary and secondary processes fail to meet the required standards, the possibility of implementing tertiary treatments remains a distant dream.

Too many questions, but no one to answer

“The state and society have made a choice to pick between irrigation water versus drinking water. When irrigation water, irrespective of quality, trumps drinking water, then the drinking water sources get contaminated. In this choice between irrigation water and drinking water, the contamination of lakes does not matter and is not given priority,” says Nirmala.

While environmental damage is a concern, the more alarming issues is the use of improperly treated water for drinking in these regions and its potential impact on people’s health.

Additionally, as reported by Deccan Herald, a report by the Environmental Management Policy and Research Institute (EMPRI) on heavy metal contamination in vegetables, warns that farmers should not be allowed by law to grow greens and vegetables using drainage and effluent waters. While the use of treated water from the KC Valley project and other similar projects may not be the core source of heavy metal contamination, given the inadequate water treatment, the potential for contamination should be explored.

The Karnataka government views the KC Valley Project as a success and so is venturing into similar projects that includes Phase two of the KC Valley Project and others, such as Hebbal-Nagawara Valley Project and Vrishabhavathi Valley Project.

These projects aim to send treated water to more drought-prone areas across Karnataka. However, in the midst of Bengaluru’s water crisis, the question of whether the city can reuse treated urban water to meet its owns demands before distributing inadequately treated water to rural areas remains unanswered.

Excellent article!

But near the end, there is a statement: “While the use of treated water from the KC Valley project and other similar projects may not be the core source of heavy metal contamination, given the inadequate water treatment, the potential for contamination should be explored.”

The statement appears to address a mild lapse, wishing for correction in due course.

But looking at the health risk to a huge population, this statement should have been far sharper, such as-

“KSPCB has failed to locate and eliminate the source of this contamination, putting a huge population at risk. An immediate probe must be launched to investigate this failure of the watchdog agencies to protect the citizenry.”

The purpose of kc valley project is to provide alternative source of water to sustain depletion of ground water in kolar & chikkaballapur dist but kspbc and other watch dog agencies have failed to maintain the quality of the treated water due to inadequate treatement which is effecting large population health.The govt whose primary responsibility to maintain good health of its population is carrying out unhealthy projects like this. Such projects should be stopped or tertiary treatment must be started immediately.